Fallout 76 Will Trigger Your Existential Crisis

Unlike previous entries in the series, the new, online-only game never justifies its own existence.

If you're anything like me, playing Fallout 76 is likely to provoke bouts of existential self-examination.

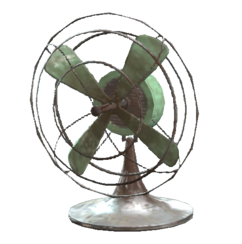

The game raises questions, such as: Who am I? What is the meaning of life? Is there a purpose to my existence? Is it to scour a desolate virtual landscape looking for desk fans while being pummeled by super mutants? To engage in clunky, frustrating shoot-outs with irradiated human husks that somehow manage an astonishing level of accuracy with various firearms? Or maybe to talk to funny robots and listen to audio diaries of dead survivors of a nuclear apocalypse while trying, pathetically, to build a defensible little fort that I will inevitably lose due to a game-breaking glitch that any real-world insurance agent, even the most devout atheist, would doubtlessly categorize as an act of god?

But mostly: Why, dear lord, why am I still playing this game?

Over the past decade or so, I have played hundreds and hundreds of hours of Fallout games—Fallout 3, Fallout: New Vegas, and Fallout 4—and I've spent similar amounts of time in the Elder Scrolls games, the sister series of role-playing games created by Bethesda Softworks. And while those games have occasionally caused me to wonder just what, exactly, I am doing with my life, I have always been able to provide an answer: I play for the stories, for the characters, for the world, for the systems of emergent gameplay, for the sheer, overwhelming, immersion of these massive, ridiculous games. And — if I am being honest—every now and then, I play for the desk fans.

To understand why Fallout 76 is such a frustrating mess of a game, you have to understand the appeal of previous games in the Fallout franchise. Since the 2008 release of Fallout 3, the main entries in the series have been single-player open-world role-playing games that you play in a first-person perspective, a lot like a modern shooter. Think of a futuristic, video-game version of Dungeons & Dragons, played by yourself, which you experience looking down the barrel of a gun (or a spiked baseball bat, or a powered punching glove, or a deathclaw gauntlet, or…you get the idea). But the Fallout series differs from conventional first-person shooters in some notable ways. First, unlike nearly all other shooters, the combat doesn't occur exclusively in real time. There's a gameplay mechanism called the Vault-Tec Assisted Targeting System (V.A.T.S.) that allows you to freeze or slow time, targeting specific parts of specific enemies, making the experience resemble a "turn-based" game like X-Com or Shadowrun or, for that matter, classic tabletop role-playing games like D&D. There are no 20-sided dies present, but the game involves a lot of hidden dice roles. This slows down the pace and makes it more contemplative and tactical, inasmuch as a video game shootout with a horde of mutated rat creatures can be.

Second, the emphasis is as much on story and character as on combat. You spend a lot of time in dialogue trees with various computer-controlled non-player characters, or NPCs. Some of these NPCs have very little to say; they are little more than information kiosks with faces. But in each of the previous games, there were more than a few memorable characters—a robot detective, an Elvis impersonator who ran a gang in a lawless part of town, a freedom-fighting retro radio DJ, irradiated ghouls who have somehow maintained their intelligence, and so on and so forth. In some cases, these characters become your traveling companions, and you spend a lot of time with them, getting to know their quirks and preferences. These are games with a surfeit of personalities, and they give the series a lively sense of the breadth and depth of human (and post-human) weirdness at the margins of existence.

It's not just about the characters, though. It's also about the world. The games are set in sprawling mock-ups of post-apocalyptic cities—Boston, Las Vegas, Washington, D.C.—that make deft use of environmental storytelling. Even when you're just aimlessly wandering, you encounter scenic dioramas that tell succinct stories, often about someone's untimely end. Some of these scenes are blackly comic; others are tragic. You end up feeling a little like a murder detective, traipsing through a world filled with the dead, examining clues to how they lived and died.

You also run across countless cities and communities, cobbled together from the ashes of the old world, struggling to eke out a measure of survival in a harsh world. Many of these ramshackle communities have ruling orders—governments or town leaders or family elders—and the storylines often revolve around internal political disputes and squabbles over local politics. The Fallout games are premised on the assumption that most people will self-organize into little bands and tribes, that most will be peaceful and some will be violent, and that, in any case, shabby politics will inevitably intrude and make life a little less pleasant. They are set in a world where government has failed, and where it continues to fail.

You also find a whole lot of leftover, pre-apocalyptic crap. In the Fallout games, there are a huge number of minor objects you can interact with: everything from paint cans to soda bottles to brooms and hot plates and batteries and duct tape and boxes of ancient cleaning products and cereal—and, well, desk fans. These items can be traded to in-game vendors or consumed for health, or, in Fallout 4, broken down and turned into parts that can be used to upgrade your weapons and armor, allowing you customize your armor and armory to a fairly obsessive degree, so long as you're willing to pick through the heaps upon heaps of stuff the game scatters around the world.

You can also build homesteads in certain locations, setting up what are essentially defensible farms. The more you build, the more they become populated by computer-controlled locals, who scrape at the ground and gripe about the misery of existence and occasionally fight off gangs of AI raiders. You're not just a scavenger; you're a wasteland combo of our last two presidents, part real estate developer and part community organizer.

It's possible to spend as much time scrapping aluminum cans, collecting glue bottles, and upgrading sniper barrels as you do fighting gigantic mutant spider-creatures. (In this way and others it's more than a little like No Man's Sky.) The games are virtual havens for those with crap-collector tendencies, and they tend to turn even the most committed minimalists into into hoarders, junk hunters, and DIY weapons enthusiasts. The appeal is in the expansiveness and immersion of the worlds, and the sense of endless opportunity they offer.

Fallout 76 resembles its predecessors in many ways: The open-world exploration, the clunky combat, the mountains of reusable junk. But it differs in one crucial aspect: You don't play alone.

Instead of computer controlled NPCs, every single other person you encounter is controlled by a real human being here in the real world, who is interacting with the same game world, at the same time as you.

There are story reasons for this; the game is set in the ruins of West Virginia early in the Fallout timeline—after the nuclear war, but before humanity began to resettle the planet. But it changes the experience from a rich, lonely fiction into an awkward social nightmare. Somehow, it makes the game feel more lonely than ever.

It means, among other things, that the combat now takes place entirely in real time, since you can't slow time for one player but not another. (A V.A.T.S. system still exists, but it's a kludgy, real-time auto-aim that often works less well than just pointing and shooting.) It means that there are no robot detectives or freedom-fighting DJs to meet, no surprisingly intelligent irradiated ghouls to befriend. It means that every community you find is dead, and that the stories are all told via the audio logs and notes of survivors who ultimately didn't survive. There are a handful of friendly robots, but they exist primarily as vendors or dispensers of mission details; they are as interesting to converse with as an automated telephone system. Press seven to start your next boring quest.

Yes, the game carries over the series' bleakly comic skepticism of government and politics (an early mission that takes you through a bombed out capitol building filled with notes and recordings that tell a story about corrupt dealings between politicians and local mining interests). But the "characters" are all long expired; the narratives are just diaries of the dead. As a result, the game feels cold and lifeless, like a long walk through a fictional mausoleum.

When you do happen to encounter another player, it disrupts any sense that you've been transported to a fictional place. Looting hot plates from a bombed-out skyscraper is still fun, in a way, until you run into Woodchipper67 or BernieFanSince09 trawling through the same building. In theory, you could team up with these people, but it's not clear why you'd want to; game objectives must still be triggered individually, coordination opportunities are limited. Fallout 76 is just more proof that hell is other people.

The presence of others is also a huge departure from the isolation that made previous entries in the series so enjoyable. When I play a Fallout game, I want to lose myself in an immersive post-apocalyptic landscape set against the ruins of a dysfunctional America. Adding a social aspect makes it more like Twitter.

Okay, bad analogy.

What all this means is that the core of Fallout 76 is collecting and modifying stuff: hunting for junk, scrapping it, and using it to build up your weapons, armor, and home base. The game takes the base building system from Fallout 4 and emphasizes it even further, but drops the socio-political aspect. You're no longer a settlement organizer; you're just building a hideout for yourself…so that you can…do more of that. It feels pointless. It is pointless. But you search and collect and scrap your way through the game anyway, because that's all there is to do. In Fallout 76, it's all desk fans.

It doesn't help that the game is riddled with bugs. Once again, the social aspect makes this worse. Previous Fallout games have been glitchy, but you could usually go back to a recent save. Because 76 is always online, there's no conventional saving (saving is essentially a way of reversing time), so if you're inexplicably booted from the server, you often end up outside of the quest area, forced to fight your way through enemies you've already killed again. There are other issues: Enemies appear in front of you with no warning, your base disappears, the stuff you've collected becomes inaccessible. The problems are so frequent and so infuriating that I sometimes wondered if the developers were actively attempting to undermine my play. Why was I playing this game?

Arguably more than any other form of entertainment, video games implicitly raise the question: Are they worth your scarce and precious time? The best video games, like the best novels or television shows or board games, are in some sense self-justifying: In exchange for your time they offer beauty, amusement, cleverness, suspense, wit, drama, pleasure, or escape. Up until now, the Fallout franchise has offered enough of these to keep me coming back. Fallout 76, sadly, fails to justify its own existence. This wasteland journey is just a waste.

Show Comments (54)