Pantera Drummer Vinnie Paul is Dead. Don't Forget His Role in Ending the Cold War.

Pantera's 1991 Moscow show helped cement the demise of a dying empire.

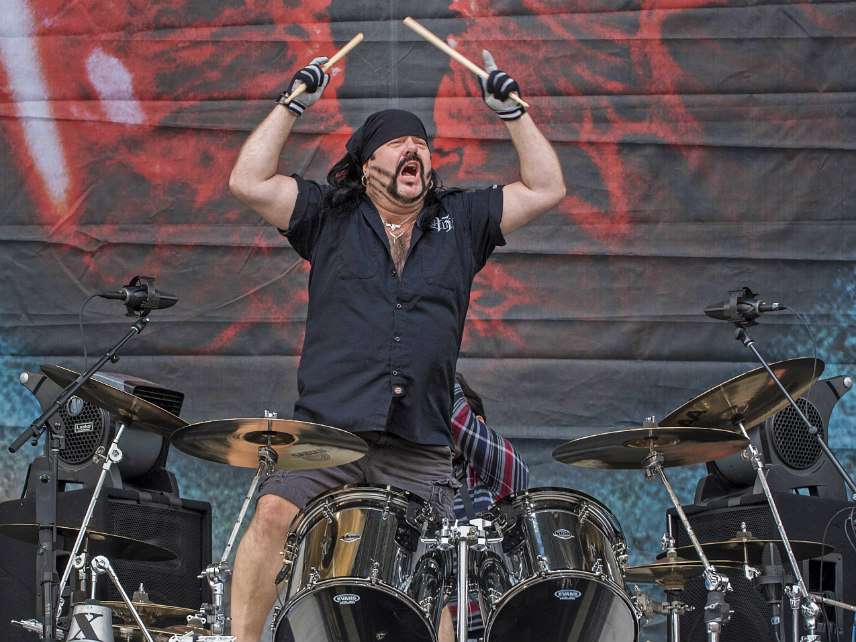

It has been over a week since Pantera drummer and American metal heavyweight Vinnie Paul Abbott passed away, and the tributes are still pouring in.

At a Sunday public memorial for Abbott—who died in his sleep at age 54—friends, fans, and a long list of musicians that either influenced or were influenced by Abbott expressed sadness at his passing while sharing personal memories of his life.

My favorite memory of Abbott is the role he and Pantera played in ending the Cold War.

In September 1991, Pantera—alongside fellow rock gods Metallica, AC/DC, and The Black Crowes—held a massive, free "Monsters of Rock" concert at a defunct airfield in Moscow, the heart of a rapidly crumbling Soviet Empire.

"It's a killer thing we are all here together, and music is the universal language," belted Pantera vocalist Phil Anselmo to roaring approval from a crowd numbering anywhere from 150,000 to 1.6 million. All had turned up that day to hear angry, rebellious music of the kind that was prohibited in the USSR just a few years prior.

Images from the concert are glorious: Pantera guitarist (and Abbott's brother) "Dimebag" Darrell headbanging along with a shirtless Anselmo; a teeming mass of fans experiencing the fringes of Western culture live and in person for the first time; groups of Soviet policemen impotently struggling to hold back the crowd.

It was a profound cultural moment. It also came at a pivotal time in the USSR's own history.

Just a month prior, a clique of diehard communist generals had tried to oust liberalizing Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev in a failed coup. Two months after the show, Gorbachev announced the dissolution of the Soviet Union, ushering in not the freedom and democracy many had hoped for, but rather a lost decade of corrupt authoritarianism, political instability, and economic chaos.

A New York Times write-up of the show reports "scattered arrests" from the day as "police officers wearing helmets and wielding truncheons chased after troublemakers and drunken youth who appeared to be well-represented in the crowd."

"More than 1,000 militiamen were on guard around the stage, and more were hidden in trucks parked farther away," notes the Times.

Nevertheless, one can also see in Pantera's 1991 Moscow show the liberating power of culture on full display.

As Reason editors Matt Welch and Nick Gillespie argue in their 2011 book, The Declaration of Independents, the death knell for Soviet communism was not U.S. defense spending or its propping up of friendly third-world dictators. Rather, it was the Eastern Bloc's irrepressible desire to join the free, prosperous world they saw on the TV show Dallas, or heard about on Velvet Underground records.

Music critic and writer Andrei Orlov made a similar point to the Times, noting that "Monsters of Rock" gave Soviet citizens a chance to openly express a long-repressed love for heavy metal.

"Look at the graffiti in the city," Orlov said. "AC/DC is written on every wall."

At a time when serious people wanted to spread freedom at gunpoint, Pantera and Abbott were liberating the youth with heavy riffs.

Rent Free is a weekly newsletter from Christian Britschgi on urbanism and the fight for less regulation, more housing, more property rights, and more freedom in America's cities.

Show Comments (21)