Why America Distrusts 'the Media' and What to Do About It

For starters, don't describe the audience as incest survivors.

How bad is the relationship between national news outlets and their audience? I'll get to the survey data in a bit, but if you bothered to watch or read about last Saturday's White House Correspondents' Dinner, you already know the answer: It's really, really bad. And it's certainly not helped when wealthy, well-connected TV journalists side with powerful politicians against freedom of expression or when Brooklyn-based scribes imagine Americans as children and Donald Trump as "a stepfather who was going to rape us."

Whatever else you can say about comedian Michelle Wolf's polarizing performance at the correspondents' dinner, in which she brutally mocked the president in absentia and administration officials seated just a few feet from her, the press came off looking even worse. Within hours of the event, NBC stars such as Mika Brzezinski and Andrea Mitchell, newly minted Pulitzer Prize winner Maggie Haberman, and other prominent journalists attacked Wolf for her raw language and untoward humor, especially her jokes at the expense of White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders. So much for freedom of expression. Although the evening was explicitly framed as a celebration of the First Amendment, even the head of the White House Correspondents' Association (WHCA), which sponsors the event, regretted Wolf's appearance. Margaret Talev, whose day job is writing for Bloomberg, wrote:

Last night's program was meant to offer a unifying message about our common commitment to a vigorous and free press while honoring civility, great reporting and scholarship winners, not to divide people. Unfortunately, the entertainer's monologue was not in the spirit of that mission.

At best, the dinner, once celebrated and widely covered as the "nerd prom" to which journalists brought glamorous guests from Hollywood, was poorly organized. At worst, the quickness with which members of the press condemned an utterly predictable (and hence preventable) attack on the Trump administration reveals a deference to power and a desire to maintain access to politicians that far outweigh any watchdog role the Fourth Estate pretends to play.

To many in the US media, the worst sins aren't bombing and killing people or embracing policies that cause mass suffering. Those are often virtures ("tonight, Trump [by bombing] became our President"). The worst sin remains: breaching civility protocols to protect DC elites.

— Glenn Greenwald (@ggreenwald) April 30, 2018

What exactly is the "spirit of the night"? Journos who cover the White House schmoozing with people they cover as if it's all just a dumb game and adversarial journalism is just theater? https://t.co/ehEeui8hTs

— Elizabeth Spiers (@espiers) April 29, 2018

Greenwald, a winner of Reason's Lanny Friedlander Prize for exposing secret state surveillance and creating platforms that expand expression, and Spiers, the original writer at the defunct alternative outlet Gawker, aren't the only journalists who criticized the WHCA for the way its dinner played out. But the response from many establishment journalists only aggravates the alienation of readers, viewers, and listeners. The purest distillation of this perspective comes from Virginia Heffernan, whose résumé includes stints at The New Yorker, Slate, and The New York Times as well as regular contributions to Wired, The Wall Street Journal, and Politico. The correspondents' dinner contretemps moved Heffernan to tweet:

When Obama left the White House in a helicopter that horrible day, I had the impression our true father was leaving & the nation was stuck with a stepfather who was going to rape us. Now I increasingly believe that the media is the mother who won't stand up for us & defy him.

— Virginia Heffernan (@page88) April 30, 2018

It's magnanimous of a well-connected journalist with a Harvard Ph.D. to identify with the plebes ("…who was going to rape us"). But the implications of the metaphor are unmistakable: Regular Americans are children who are defenseless against a predator. "We" must be protected, either by President Dad or Media Mom, because we have no agency, no power, no strength of our own. Forget the fact that even though Trump was charged with sexual harassment and assault by many women, he won 2 million more votes than Mitt Romney managed; that must be evidence of a political-sexual Stockholm Syndrome. Trump has been repeatedly rebuffed by the courts and, from time to time, even by his own party in Congress. I have no love for him, but to cast Americans, including his supporters, as children incapable of independent action or thought only confirms the critique of the press as an elite that has more in common with D.C.'s political class than jes' plain folks toiling away at mundane jobs in flyover country.

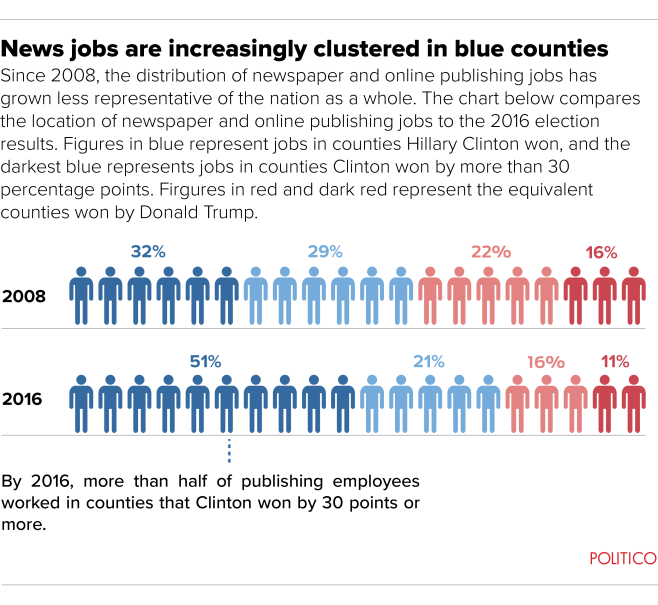

Do most members of the media see their audience with this mixture of pity and contempt? Journalists do seem to be increasingly concentrated in the well-heeled, coastal enclaves that breed such attitudes. As Jack Shafer and Tucker Doherty wrote last year at Politico,

The national media really does work in a bubble, something that wasn't true as recently as 2008. And the bubble is growing more extreme. Concentrated heavily along the coasts, the bubble is both geographic and political. If you're a working journalist, odds aren't just that you work in a pro-Clinton county—odds are that you reside in one of the nation's most pro-Clinton counties. And you've got company: If you're a typical reader of Politico, chances are you're a citizen of bubbleville, too.

While newspaper jobs, which were scattered around the country among local dailies and weeklies, have been halved since 1990, online media jobs have grown. But these new gigs are clustered in just a few places. Shafer and Doherty explain:

Today, 73 percent of all internet publishing jobs are concentrated in either the Boston-New York-Washington-Richmond corridor or the West Coast crescent that runs from Seattle to San Diego and on to Phoenix. The Chicagoland area, a traditional media center, captures 5 percent of the jobs, with a paltry 22 percent going to the rest of the country. And almost all the real growth of internet publishing is happening outside the heartland, in just a few urban counties, all places that voted for Clinton. So when your conservative friends use "media" as a synonym for "coastal" and "liberal," they're not far off the mark.

Not so long ago, journalism was a trade that was open to high-school graduates. During the last several decades, writing for a living has been professionalized to the point that most journalists have a college degree and an increasing number have majored in journalism. That trend only increases the distance between news producers and news consumers.

All of this matters because the news media play a unique role in society. Earlier this year, the Knight Foundation released a report based on a national survey of 19,000 people. Among its findings:

More than eight in 10 U.S. adults believe the news media are critical or very important to our democracy. They see the most important roles played by the media as making sure Americans have the knowledge they need to be informed about public affairs and holding leaders accountable for their actions.

Yet respondents lacked confidence in print, online, TV, radio, and cable sources, with fully 66 percent agreeing that "most news media do not do a good job of separating fact from opinion." In 1984, the corresponding figure was 42 percent. Only 30 percent said the media did "well" or "very well" at holding leaders accountable, while 42 percent said the media performed this function "poorly" or "very poorly."

Nothing that's happened in the last week will inspire more confidence that the press is comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable. Sadly, even when it tries to police and critique itself, the press seems likely to inflame the situation by insulting the intelligence and autonomy of its audience. Few industries do well by alienating their customers, and the media are proving no exception.

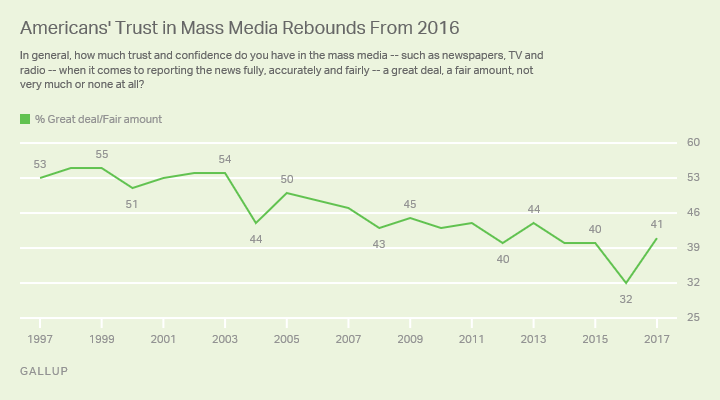

What can be done? In an age when newspapers and other sources that at least aspired to be "objective" are declining, the future belongs to viewpoint-driven journalism. That isn't a bad thing, even if it means that "the media" as a general category might never regain the public confidence it had in the mid-1970s, when 72 percent of Americans told Gallup they trusted the press. Objectivity has always been something of a con, since the selection of stories, of what counts as news and why, has always been hidden from view. So even a story that presents "both sides" can have an agenda despite its seemingly evenhanded approach.

Audiences are increasingly drawn to highly personalized and idiosyncratic approaches that emphasize drama, personality, and viewpoint. Podcasts represent the democratization of radio, and the most popular podcasts tend to be ones that push an agenda and have outsized personalities as hosts. Narrative journalism, blogging, and other popular forms don't hide behind the royal we or pretend to be omniscient. But if objectivity is elusive, impossible, and unattractive, that doesn't mean that basic codes of fairness and engagement shouldn't be front and center in contemporary journalism. Not misrepresenting opponents' viewpoints is a good a place to start, as is foregrounding biases and predispositions rather than hiding them. Admitting errors and correcting them in real time is a prerequisite, and so is engaging the audience, which long ago stopped being passive (if it ever was).

According to the Knight Foundation survey, Americans are split "on the question of who is primarily responsible for ensuring people have an accurate and politically balanced understanding of the news," with 48 percent saying it's up to individuals and 48 percent saying it's up to the media. Either way, Americans want trail guides to their world and what's happening in it, not infallible experts who issue ex cathedra statements with Pope-like certainty. They also want choice and variety and don't expect, say, the Associated Press to follow the same blueprint as Reason, even if they expect each of us to adhere to our missions and ethics. The turn to the "artisanal" matters every bit as much in journalism as it does in restaurants, woodworking, and crafts. People want to know what you believe, how your shit is sourced, and that they can trust you to live up to your word. That should come naturally, if not easily, to journalists.

Years ago, pioneering blogger Ken Layne notoriously proclaimed, "It's 2001, and we can Fact Check your ass." His specific target was Robert Fisk, a reporter whose last name was turned into a verb signifying a point-by-point refutation of an article or argument. Now it's 2018, and readers can still fact-check journalists' collective ass. They will respond more favorably to those of us who make it easy for them by being upfront, honest, and responsive without having to be asked first.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

I'll take leftist hacks and political activists for $100, Nick

You are just a rightie back. Not better.

Leftist or rightie, if the media really wants to regain the trust of the American public, it could begin by energetically condemning the refusal of a single, isolated judge in Manhattan to imprison our nation's leading criminal "satirist." This man walks free because of one judge, after all our efforts? This is an outrageous development that needs to be vigorously protested on every level. See the documentation at:

https://raphaelgolbtrial.wordpress.com/

The right is, in fact, better than leftists. Leftists base their entire philosophy on subjugation and are slowly trying to implement the government organs described in 1984.

But I'm sure we can all agree, left or right, that inappropriately deadpan Gmail "parodies" are only okay if they are "puerile" enough, or if they express an "idea," and that if they also risk damaging a reputation, then they must be suppressed and, where necessary, punished by jail? This is the conclusion reached by a distinguished panel of federal judges, call them leftist or righties, as you wish; and the refusal to jail a perpetrator after such a ruling comes down is a disgrace to our great nation.

"reveals a deference to power and a desire to maintain access to politicians that far outweigh any watchdog role the Fourth Estate pretends to play."

That was the big takeaway from this correspondent's dinner or are you referring to the ones between 2008 and 2016, because that would make more sense.

It's pretty clear that the fake controversy over the comedian at the correspondent's dinner and the push back from some in the media was due to the fact that it perfectly highlighted how biased the press has become. Mainstreaming a conspiracy theory, of which no evidence has yet to be shown, isn't helping it's credibility either.

""highlighted how biased the press has become"'

Some may say biased. Some may say infiltrated with political operatives trying to control the message(s). When you look at how many ex-democrat operatives have moved to the media, there is evidence of the latter.

"Mainstreaming a conspiracy theory, of which no evidence has yet to be shown, isn't helping it's credibility either."

The local rag (SF Chron) has a special section: "The 45th President", where, every morning, you're treated to the latest dose of lefty gossip regarding Trump:

'Somebody's hairdresser's uncle's kid heard that Trump was screwing sheep!!!'

You'd think there might be an adult there with the ability to be embarrassed, but seemingly not.

That is literally how Trump became a conservative figure.

I agree. That is how Trump came into politics. But, if my memory serves me right, I don't remember major news outlets propagating that conspiracy. I was criticizing a media narrative. Do try to keep up.

So Fox is back to not being a "major news outlet"?

Fox's news division did not push that conspiracy. I find it unsettling how detached from reality you are that you can't accept the truth of what occurred.

... right... well, that's where I'm checking out for today then. I may be bored, but if you're going to go all ad hominem I can't imagine this will be fun.

That said, at least show some creativity in your attacks. "Crazy" is a bit low-hanging fruit.

You must not mean the "Birther" conspiracy right? The one that FOX and Trump pushed with gusto for 8 years.

Or the "Benghazi" conspiracy?

Or the "Email" theater, where a Democrat is held to a higher standard than current GOP office-holders who do the exact same thing.

Right?

The one that FOX and Trump pushed with gusto for 8 years

You proglydytes seem to know more about what Fox broadcasts than any of the people who actually watch it.

Or... and this just me being whacky...

We hear what conservatives believe and we take the time to look it up and see for ourselves. Maybe we "proglydytes[SIC]" are just handicapped by our insistence on hearing both sides and researching the facts. Unlike FOX.

We hear what conservatives believe and we take the time to look it up and see for ourselves.

That you believe conservatives don't do the same thing is one of your sillier pretensions.

I doubt that you actually watch Fox News. You have copied and pasted this from the bubble of news and opinion that you have constructed for yourself.

Sure, Fox leans to the right, along with 40% of the country. On the topics that I have some expertise in, I find them no more biased than ABC, CBS, MSNBC, CNN, NPR, the New York Times and the vast majority of the institutional press that are biased to the left. On Fox, I find that both sides of the argument are usually presented, even if one is favored. The rest of the institutional press sometimes leaves out one side of the argument altogether, or presents it as evil and crazy. If you turn off Fox and never hear a contrary opinion, won't you cease to understand the perspective of nearly half the country over time?

Fox News is far from perfect but on any given topic, I can reasonably expect them to make an attempt to present more than one side of the issue at hand. I read all sides of the political spectrum, and the New York Times has become the worst of all. The "newspaper of record" simply leaves out giant parts of a story in order to push its agenda. And this is very common on the left / liberal side - topics are chosen to fit the narrative, and then the stories are further slanted to fit the narrative.

Perhaps you should actually start watching Fox News in order to criticize it more effectively.

Those on the left will never check out Fox News. They are blind to there being opinions other than their own. I also read news from both sides and have always noticed that Fox usually does provide opposing guests and the left leaning media usually does not. I am center right myself but the left is just falling farther and farther away from me. The past presidents the left praised are nothing like the left of today, not one bit.

"Proglydytes"

That's gold

Sweet, sweet gold - and I will not hesitate to steal it if the right moment arises

I love how you water carriers try to downplay a Secretary of State having an unsecured private server in the basement of her private residence as "email theater". It shows just how much of a disingenuous hack you are.

Especially when we have Comey's own press conference to throw in your faces: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WIARMMtUdZQ

Now, where are all these instances of cabinet level Trump admins having private servers containing classified information. I'm sure the media has covered them in depth since they've finally found their balls and are holding the President to task again.

Even if all of Fox News trumpeted the whole Birther movement every day of Obama's presidency, they constitute a sliver of the overall MSM.

Which, if memory serves, roundly mocked the Birthers (as they should have).

So that's not even in the same ballpark as Russiagate. Do try again.

FOX news isn't a "sliver of the overall MSM" where news is concerned. They hold the largest share of the viewership. (Or did... they're declining as the Boomers age out.)

Funny thing about "Russiagate," it's being run by a lot of Republicans and agents with strong bipartisan support. I appreciate how inconvenient it may be to have a presidential candidate at least tangentially associated with their opponent's emails being hacked by a hostile foreign power, offered access to that content by agents of the foreign power (an offer your own son was excited about), and then later have those emails released to Wikileaks to damage your opponent. And then the candidate wins.

FOX news isn't a "sliver of the overall MSM" where news is concerned. They hold the largest share of the viewership. (Or did... they're declining as the Boomers age out.)

They hold the largest of cable news. The Big 3 broadcast all still outperform Fox news.

Here's some Broadcast news Stats

Here's some Cable news stats.

Thanks for those.

What stands out to me is that it looks like around 30-40 Million Americans, at max, are watching televised news. There's over 320 million of us of which about 230 million are adults. Where are the other 75-80% getting their news from? Facebook?

Some people get their news from a news aggregation website and then check all sorts of sources ourselves instead of being told what the news is according to places like Communist News Network.

Many people don't pay attention to the news at all.

CNN crackpottery sticks in the the average person's mind more than Fox.

It's because people know that Fox News is biased, and they don't really claim not to be. CNN claims to be unbiased, even while they wear that bias on their sleeves.

That, to me, is the big difference.

Their slogan was literally "fair and balanced"

FOX News have always dismissed and even ridiculed the whole 'Birther Conspiracy', ever since Hillary started it in 2008, when she was fighting Obama for the Dem nomination.

"highlighted how biased the press has become"

Become? The media has ALWAYS been biased. The internet is just making it harder for these hacks to hide. Going all the way back to Walter Durante, who won a Pulitzer prize lying about the success of the USSR in the 1930s. Walter "the most trusted man in news" Cronkite willingly lied for political gains. For example, he reported the Tet Offensive as a loss or, at best, a stalemate for the US, when the Tet Offensive was a stunning victory for US forces, with the NVA being completely annihilated, taking two years to recover from the catastrophic loss. At every turn, he lied about US success after success in Vietnam and could relied upon to routinely put forth whatever propaganda supported leftwing causes.

It was a dinner party, not an in depth report. The complai r was that Wolf went too far and crossed a line for mean spirited incivility (espevially against female WH staff). You can disagree with that point of view, but it is not a reflection in itself of hiw journalists are supposed to professionally interact. All it reveals is a juvenile attitude that rudeness equals authenticity.

Which perhaps makes Gillespie and Trump not so different.

The type of show this person performed might have worked OK on a lefty comedy show with an audience full of lefties but was just not the place to perform a hit piece. Just was a terrible idea.

"but it is not a reflection in itself of hiw journalists are supposed to professionally interact"

When you're event is called "The White House Correspondence Dinner" it IS a reflection of the journalists professionalism.

In a sane world Michelle Wolf would never be hired for a comedy gig ever again, not because she attacked anyone but because she's not remotely talented or even mildy amusing.

Who are the funny comedians nowadays? Because the news I follow doesn't highlight the funny ones, but the other kind. Who am I missing?

jon laster?

Bill Cosby?

Dave Smith

http://www.reason.com/reasontv/2017/0.....tas-comedy

Dough Stanhope.

* Doug

Doug Stanhope:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Z8W5yQyzk8

Lavelle Crawford, dude. Fuckin' hilarious.

No love for Bill Burr?

Goebbels?

Some I like:

Stand Up:

Norm MacDonald

Mike Birbiglia

Doug Stanhope

Bill Burr

Rory Scovil

Maria Bamford

Dave Chappelle

Jim Gaffigan

Writers/Podcast:

Scott Auckermann

Lauren Lapkus

Paul F. Thompkins (basically, these top three mean listen to Comedy Bang Bang)

Brian Regan.

Nick Di Paolo and Jim Norton.

No love for Bragg and Heaton?

I miss Heaton.

And yikes that voice. Could you imagine waking up to that every morning?

I may have one issue with Wolf's performance. Was it supposed to be a clean show? If so, the foul language would be an issue. If not, then no big deal. I have no problem with the comedy or the attempt thereof.

If you insist that you are objective and credible sources of news, then be that. Don't be the propaganda arm of the Democratic Party and socialists.

Objectivity in reporting is impossible. People need to realize that.

Everyone does. Nobody expects perfect objectivity. What people object to is the pretense of media figures who claim to be neutral and unbiased fact-finders even as they shill, transparently and consistently, for the left.

I don't believe that this sudden sickness and sinking trust ratings come from people only recently getting tired of the press being biased. The bias is inherent, and if everyone already knew then this is not a new thing at all. I don't believe they are any less biased now, or in any particularly different direction from before.

I truly believe it is because feel they are now being lied to. But I see many people clamoring for improved and unbiased reporting. And so they are either advocating for something they know to be impossible, or they do not know it is impossible.

"Objectivity in reporting is impossible. People need to realize that."

This is the classic Leftist attempt to destroy concepts.

True objectivity is impossible, *therefore* all communication is propaganda, so stop complaining about it when we do it.

True consent is impossible, *therefore* all interaction is nonconsensual, so stop complaining about our totalitarianism.

It is possible to be quite objective, while still having a preference, and still not *intentionally* misrepresent reality, making a good faith effort to present the facts.

True objectivity is impossible, *therefore* all communication is propaganda, so stop complaining about it when we do it.

No, the point is everyone needs to know the limits of communication and take this into account when analyzing the world.

It is possible to be quite objective, while still having a preference, and still not *intentionally* misrepresent reality, making a good faith effort to present the facts.

Sure, but even without intent, there is always a bias. We as humans do not have access to truth and objectivity. We all analyze things from our own sphere, it's important to realize this about ourselves, and have some doubt about things.

I don't even mind people propagandizing for their favored political agenda, just don't pretend you're just reporting the facts and don't call people liars or mentally ill or any of the other insults the left hurls when they disagree with you.

(Some) Americans distrust the media because of a decades-long right-wing smear campaign that pushed the myth of a "liberal bias." When in reality, reporters aren't so much driven by ideology, but rather by pursuit of a worldview based on facts and science. It's only because conservatives have retreated into their reality-denying echo chambers that the rest of the media appears, to them, to be pushing an agenda.

I disagree. When journalists make the occasional error, they handle the situation in an honest, professional way. Like Joy Reid just did when she explained that some of the problematic content on her old blog was written by her, but that the rest was inserted there by hackers.

"(Some) Americans distrust the media because of a decades-long right-wing smear campaign that pushed the myth of a "liberal bias.""

Your material is getting more than lame:

"Former NPR CEO opens up about liberal media bias"

https://nypost.com/2017/10/21/th

e-other-half-of-america-th

at-the-liberal-media-doesnt-cover/

Link custom for YOU!

Meh. A known liberal bias is fine provided the information they share is true. Same with conservative bias.

But when a site like Breitbart, which gives zero shits about the facts, can get a Whitehouse press pass, we've pretty much flushed the whole idea of factual journalism down the toilet. FOX News at least managed to bolster their reputation with factual local news, even if their national news was pretty much Republican Party propaganda.

Remember when FOX News tried to claim Comey resigned? That's not a case of bias, that's right out of the Pravda playbook.

Comey should have resigned. He was terrible. Maybe that's what they meant. You didn't provide a citation, so who knows. Not a lot of FOX watchers around here, except Tony and yourself.

So you got Breitbart and FOX for the right.

CNN, WaPo, Salon, NYT, CBS, NBC, ABC, Huff post, most major metro newspapers, Pravda, and Commie news coming out of China and Cuba are clearly lefty biased.

Remember when the New York Times claimed Aleppo was the capital of ISIS? No, you probably don't, because it wouldn't fit your narrative about how leftist outlets care so much about facts.

What's Aleppo?

16 Fake News Stories Reporters Have Run Since Trump Won

Which news outlets? The Guardian, New York Magazine, Politico, CNN, New York Times, Time, Slate, Vox, Washington Post, and the Associated Press figure prominently in the reporting and distribution of these fake news stories.

Here is just one sample: fake news on Betsy DeVos:

shawn_dude|5.3.18 @ 5:31PM|#

"Meh. A known liberal bias is fine provided the information they share is true. Same with conservative bias.

But when a site like Breitbart, which gives zero shits about the facts, can get a Whitehouse press pass, we've pretty much flushed the whole idea of factual journalism down the toilet."

You seem to be bent on proving an contrarian can easily be an imbecile.

Did you see the claim I was responding to, or did you simply spout bullshit out of idiocy?

You're accurately stating the media position on its own bias (though I know you're a parody).

When journalists make the occasional error, they handle the situation in an honest, professional way. Like Joy Reid just did when she explained that some of the problematic content on her old blog was written by her, but that the rest was inserted there by hackers.

Okay, that was funny.

"...an honest, professional way..."

Like LYING!

Fails to meet either of your criteria.

"...reporters aren't so much driven by ideology, but rather by pursuit of a worldview based on facts and science."

This guy wrote a book about a worldview based on science:

'Socialism: Utopian and Scientific', Friedrich Engels (1880)

How'd that work out?

"When Obama left the White House in a helicopter that horrible day, I had the impression our true father was leaving & the nation was stuck with a stepfather who was going to rape us. Now I increasingly believe that the media is the mother who won't stand up for us & defy him."

Did some mainstream journalist actually tweet that?

Maybe Twitter plays a useful role in giving us the unvetted, unedited views of journalists, revealing that they have the attitudes their critics always said they had.

"When Obama left the White House in a helicopter that horrible day, I had the impression our true father was leaving..."

Good god. I don't have enough faces or palms to adequately facepalm this. If I ever worship some political hack like this, please for the love of god, smack me in the mouth.

Let us not dwell overlong on what might drive a father to knowingly leave one of their children to be abused by a step-parent, of course! Just because they're your 'real dad' doesn't mean they actually like you.

I thought Wolf's performance was pretty funny (the small bits that I saw)-- I thought she did a pretty good job at roasting the guests, but I admit I like that sort of format, so I might be biased. Whether or not the WHCD is the place for that, I can't say. It's possible that I'm naive in that I still can't figure out why there is a WHCD.

I guess in the spirit of free speech, Wolf can say whatever she wants, and the press can say whatever they want in criticism. It all seems like a bit of a tempest in a teapot. Of course, it's probably wise to remember that someone is in control of who gets invited in the first place, so there's a certain amount of controls, filtering and discrimination going on in the first place. For instance, I'm not invited to the dinner, and I've got a cache of still-untold Agnew jokes that totally would have killed.

""I've got a cache of still-untold Agnew jokes that totally would have killed.""

Is this thing on?

Fun fact: Spiro Agnew is an anagram of 'Grow a Penis'.

"I guess in the spirit of free speech, Wolf can say whatever she wants, and the press can say whatever they want in criticism."

And people can vote for whomever they want. That why the press is so freaked out. Wolf is exactly how you get more Trump.

I'll grant that some of the people attacking Wolf are a bit too hysterical about it. But criticizing her performance is not some sort of attack on the 1st Amendment or freedom of expression.

Agreed. Pleather Jacket's "[s]o much for freedom of expression" exclamation effectively cutting his own argument off at the knees.

(Hint for Nick: Them, you, me; It's ALL freedom of expression.)

I don't think disavowing Wolf was any kind of threat to the First Amendment, which restricts the government, not press associations, for goodness' sake.

If they were supposed to be celebrating the First Amendment, then they should certainly apologize for selecting a speaker who discredited First Amendment values - imagine if they'd invited a "comedian" who mocked the press for its superstitious devotion to liberty and free expression.

Wolf mocked First Amendment values by saying stuff which, though fully protected by the First Amendment, was not the sort of thing you highlight if you're showing the benefits of that amendment. Wolf's speech is more like the price we pay for freedom, in the form of silly speech.

Where has Humphrey Bogey's newsman-as-hero gone? "This paper will fight for progress and reform. We'll never be satisfied merely with printing the news. We'll never be afraid to attack wrong, whether by predatory wealth or predatory poverty."

That "most/more news jobs are in blue counties" bit interests me, but the surprising part is that it used to be more uniform and less clustered.

I mean, think about it. We already know that blue counties trend more urban, and red counties trend more rural. Absent any other information, just a measure of how "rural" or "urban" a place is, you have a pretty good guess at it's politics.

Similarly, urban unemployment is lower then rural unemployment.

So it follows that "red county" unemployment is probably higher then "blue county" unemployment, though I can't find data sets that back up that specific thesis.

So even before we talk about the nature of specific jobs, that more job openings will be in an "urban" area (which correlates well with "blue"), then a "rural" area (which correlates well with "red") is a reasonable hypothesis.

Or to put it another way...more people live in "blue counties" then "red counties", and those counties have lower unemployment. That more jobs of type X are found in "blue counties" then "red counties" isn't a dangerous starting point before you start considering the tasks of a specific job.

So to me the weird thing isn't that so many journalists live in "blue counties", it's that it used to be more egalitarian.

You are forgetting the suburbs, which are beating cities and urban areas. Suburbs still trend "red", although that may change.

I forgot nothing (NOTHING!!!). That's just sitting in the fuzzy 4th paragraph where I explicitly step away from "this is known" to "this is a reasonable hypothesis" and called out that I didn't have a supporting data sets.

Which is to say, yeah, they don't sit at the extremes of the trend line of either red/blue or rural/urban, but in the middle of both.

Wow. That's an insane reply. I was just noting that you forgot suburbs and that your hypothesis was exceptionally shallow.

Dude, if I was invested enough in any hypothesis to go beyond "shallow", I wouldn't bother taking it to you folks.

That said, are you just talking about the first four words? And people say I can't take a joke.

His hypothesis is only "shallow" in that he gave it about 5 minutes of thought. But generally speaking, he's likely on the right track.

The highest population densities are on the coasts and in big cities and they have a strong trend towards liberal politics. The lowest population densities are in the burbs and rural areas and they tend towards more conservative politics. Evidence for this is easily found by looking at the county by county Trump vs HRC map.

Aside from uniquely suburban or rural jobs (like farming), it's very likely that any job is more concentrated in big blue cities than elsewhere for no more complicated reason than employees (people) are more concentrated there to begin with.

"Breaking News! Science says more tropical fish found in oceans than in the American deserts! Scientists are puzzled! (as to why this is news to anyone.)"

Because there are no big cities outside of the northeast and West Coast?

Where are the fastest growing cities again? Oh right, the interior Southwest.

Most housing in the true 'urban' heart of the cities I've visited are a bizarre mix of section 8 and buyable apartment homes that sell for millions, and I'm not so sure how many people actually live there vs. the suburbs.

It is true that as the Federal leviathan has grown, it's put a lot of people out of work through regulations out there in Red Country though. This empowers the centralized power structures of corporate behemoths, which primarily only exist in urban environments.

So, really, this isn't surprising to me.

Or, shorter version, as small businesses fail en masse you'd expect to see people concentrate in cities where the few remaining opportunities lie with the giant conglomerates.

I'm not sure I buy this argument. Most businesses are "small businesses" by number.

It's also true that a large percentage of small businesses fail in the first few years for no more complicated reason than the proprietors did something foolish.

And, as I walk through my big city (SF), I see more small businesses thriving than big ones (though the big ones are easier to see in their giant skyscrapers and employ far more people.) In some ways, as people concentrate in the big cities, there is more opportunity for small business to gain a share.

So even before we talk about the nature of specific jobs, that more job openings will be in an "urban" area (which correlates well with "blue"), then a "rural" area (which correlates well with "red") is a reasonable hypothesis.

There's some further nuance between "urban" and "rural". There are a number of urban areas (high population, not farmland and rolling hills) which skew conservative. Many of these "urban areas" are in what some call "flyover states". Ie, often times we're really discussing coastal urban areas vs interior ones.

Nuance, sure. But the trend line/correlation is pretty strong no matter which state you're in (coastal, flyover, or in the middle of nowhere).

You got "rural" in California? Goes red. Got "city" in Alabama? Goes blue. There are exceptions, of course, but even when you do find a "red" city, it's never gong to be as red as the surrounding rural areas, and the reverse holds true as well (you don't find rural areas that are more "blue" then the cities they surround).

So yeah, "flyover" trends red, but their cities are always distinctly pink.

Consider: Austin Texas. Seat of GOP power in the biggest Red state (and only one of two that pay more into Federal taxes than they consume.)

Well, it's true Austin is the main bastion of Liberals in Texas. Houston might be red, I'm not positive of that, and I think Fort Worth might be as well. Dallas and San Antonio, though, are decidedly blue.

I'm surprised to hear San Antonio, massive military installation and all, is blue. Cities with big military bases, like San Diego, tend to run more conservative.

Tucson has a big AF base and is also the only blue city in the state.

Haha, you're hilarious. People who pay more in taxes than they get out mostly vote Republican; people who get more than they pay mostly Democrat.

And here's where you do a 180 and decide that now being poor is good rich bad and that just shows that Republicans are oppressors or some bullshit.

Actually, if you read Andrew Gemlan's Book on the subject, economic class is the driving factor. Poor southerners tend to vote Democrat, suburban middle and upper class northerners Republican. Regional differences tilt the balance, but not nearly enough to flip the much more important economic factor.

Obama is our "true father"? Ye gods. That's even worse than that other broad who carries an Obama doll around in her purse. To think that people so infantile have the brass to regard themselves as an elite.

""Obama is our "true father"?''

Some would have said the same of Darken Rahl.

Except this isn't a Goodkind novel.

It's nice to know I'm not the only one here who's read them.

Fantasy with a blatant (and occasionally excessively preachy) objectivist slant should be one of the things people on here are aware of. Haven't finished his latest trilogy because it's lost the core of what made the SoT series so good (and Zedd...)

He might be a bit of a hack writer, but I really enjoyed the books and characters. His excessive repetition and ideological preaching wear down readers in some spots even if I already agree with his premise.

You misunderstand.

You label them "elitist" in order to distance them from "real people." They don't consider *themselves* to be elite.

You're falling for your own propaganda.

They sort of do, though, even while they rarely say it. You can tell because of their statist positions that demand that others obey their particular way of living their lives.

Listening only to what a person says means you know less than half of what they mean.

I think you're reading your own biases into this.

Consider my reframing of your argument:

"You can tell that conservatives consider themselves better than us because of their moral positions that demand others obey their faith-based positions and live according to Christian beliefs even if they don't share them."

Liberals are statists because they believe the power of government can offset the very real risks of runaway capitalism. Conservatives generally disagree with this, which is fine, but their faith in "The Free Market" or the Christian Bible isn't any different.

And, as an addendum...

Using "Big Government" to enforce Christian moral standards on non-Christians is also "statist."

"Your faith in Darwinism is just like my faith in creationism!!" No, it isn't.

Markets are more effective at allocating resources than states. That's not a rival faith. It's the truth. Get over it.

"You can tell that conservatives consider themselves better than us because of their moral positions that demand others obey their faith-based positions and live according to Christian beliefs even if they don't share them."

... which is exactly what you've been saying for 50 years while clinging desperately to your Marxist substitute for religion utterly unaware of how fucking stupid you are. Thanks for proving the point.

You label them "elitist" in order to distance them from "real people." They don't consider *themselves* to be elite

Their paychecks and membership within the country's various cathedrals of influence would seem to indicate otherwise.

Of course they don't consider *themselves* to be elite, because their whole worldview going back to the French Revolution is based on the idea that they're oppressed underdogs, and that every time things don't go exactly the way they want it to, it's because those in power won't give it to them.

Leftism, at its core, is a very childish outlook that's constantly being enabled just to shut up the tantrum-throwers.

Arguments like this would be easier to swallow were it not for the various tantrums conservatives throw when they don't get their way.

Abortion

Segregation

Gay Marriage

Transsexuals

School Prayer (Christian only)

Obamacare

Confederate Statues

There is some important difference between the right's position regarding the state and the left. The right can (usually) be boiled down to "we want our group to be able to live the way it wants absent other people's involvement and if someone doesn't like it they can leave, but if they don't these are the rules." The left, however, is more like "We want everyone else to live how we want and you don't get any option to leave because we want our way imposed universally."

Granted... issues of abortion are different because to many, especially on the right, it is an active force applied onto someone else thus violating their right to life rather than a prohibition of action (like outlawing gay marriage).

Those are not universal rules so a "but what about...!!!1!1" on some particular topic doesn't mean much.

shawn_dude|5.3.18 @ 6:03PM|#

"Arguments like this would be easier to swallow were it not for the various tantrums conservatives throw when they don't get their way.

Obamacare"

Shawn _idiot.

STFU.

Arguments like this would be easier to swallow were it not for the various tantrums conservatives throw when they don't get their way.

The difference is that mass media and the nation's intellectual class can only explain their losses through wild conspiracy theories about Russian hacking, rather than the fact they just picked bad candidates.

shawn_dude|5.3.18 @ 5:15PM|#

"You misunderstand.

You label them "elitist" in order to distance them from "real people." They don't consider *themselves* to be elite."

You're approaching idiocy if you think they don't.

The fact that that women has a Harvard PHD is further proof, as if any were needed, that you should never hire anyone who has been associated with that school. What a fucking pinhead.

Hillary Clinton was caught on camera clearly falling unconscious and being carried into a van, and nearly everybody in the press called anybody concerned about her health a conspiracy theorist. Many even denied that she was ever unconscious, or that she "tripped" into the van.

The press are all propagandists. Worse than fake news or lies is the selection of what to report. We live in a country of 330,000,000 people. You can make people believe any narrative you want, as long as you report on rare instances that support it and ignore others that don't. When nobody in the mainstream press reports on what should be important stories because they don't fit a narrative, people justifiably go to right-wing websites that do. It's their own damn fault.

Don't worry, Hillary Clinton will power through.

She was also caught on camera birthing an alien into a glass, according to InfoWars.

No no, you're thinking of the snuke.

Oh, she's definitely an alien.

Hillary Clinton was caught on camera clearly falling unconscious and being carried into a van, and nearly everybody in the press called anybody concerned about her health a conspiracy theorist. Many even denied that she was ever unconscious, or that she "tripped" into the van.

Just imagine if that guy hadn't filmed her getting thrown into the van like a sack of potatoes.

""the press called anybody concerned about her health a conspiracy theorist""

She lied about her cough. No one in the press called it a cover up. Trump could lie about where his dog took a crap and it would be front page.

Count Dankula discusses the mainstream press and general zeitgeist.

Could it be because so much of what the MSM is selling is a steaming heap of BS?

"But if objectivity is elusive, impossible, and unattractive, that doesn't mean that basic codes of fairness and engagement shouldn't be front and center in contemporary journalism. "

The irony of calling for basic codes of fairness in defense of a president who shows no understanding of the concept and flaunts it at all opportunities. Meanwhile, birtherism and pizzagate are ignored in order heap scorn on folks who were shocked that one of their own (liberals) behaved in many ways like our president (if our president was fond of using full sentences with complete, logical trains of thought.)

This article deserves nothing but massive eyeroll.

Billions in free publicity.

Just curious. Are you reading Gillespie as defending Trump here?

In the context of posting it to this site, yes, generally. Partly, too, because I recognize how this audience will interpret "mainstream media" to mean "only liberal media." Further, her "in absentia" comment reads to me that she finds fault with insulting the president at an event that presidents normally attend and are often roasted at but at which our current president has opted to avoid.

In the grand scheme of things, I think a disrespectful media is far more preferable than a president who believes the media should be jailed for publishing things he doesn't like.

1. He absolutely was not defending Trump and you'd be hard pressed to find a more vocal opponent that writes for Reason then Nick.

2. Gillespie is a he. At least, the jacket and hair say that.

3. Man it would suck if Obama actually worked to do that...

If Obama wants a journalist jailed, then they are therefore not a journalist anymore!

By "she" I think he meant Michelle Wolf, who made a comment about Trump being "in absentia" at the WHCD.

Except the author isn't defending Trump, and where's your concern about leftist media outlets supporting the Steele dossier conspiracy theories about pee fetishes? Are you upset with Jonathan Chait? Or the "Russians hacked wikileaks' conspiracy theory

Do you aspire to be a partisan hack?

Do you aspire to be a partisan hack?

He's happy to stay a useful idiot because at some fundamental level he realizes he's too stupid to rise to the level of partisan hack.

Fiona asked me: Can we shoot them?

There a bunch of whiny bitches.

They're...

Obama and his wife are megalomaniacs.

When Obama left the White House in a helicopter that horrible day, I had the impression our true father was leaving & the nation was stuck with a stepfather who was going to rape us.

Fuckin' LOL. I doubt Heffernan took much of a break from her daily bender of box wine to think that analogy all the way through.

Nothing like comparing Obama to a deadbeat dad who walked out on his kids (and a black man, no less!), and thinking that puts him in a better light than Trump, who has to deal with the emotional fallout from that abandonment.

If "psychologists" wanted to weigh in on politics, the daddy issues of Bush, especially Obama, and Hillary would've been the best place to start.

I mean, "Dreams From My Father" (who abandoned me...)

Just about the most pathetic thing I've ever seen in politics. Up there with Boehner, McConnell, and Schumer crying on the Senate floor. And the gun control sit-in...

I always found it hilarious that the pundits and comedians who constantly made fun of Bush's daddy issues never even touched the more blatantly obvious daddy issues of Obama. He spent his entire life trying to impress a dad who abandoned him, wrote an entire book about it, and completely abandoned his half-white identity despite the fact that he was raised entirely by his white middle-class family.

And almost all the real growth of internet publishing is happening outside the heartland, in just a few urban counties, all places that voted for Clinton.

Exactly. 90% of the news is coming from The Bubble.

Surprised SNL did a joke to bash lefties.

I've always been a fan of the tactic where, if you meet someone who works in the news or media, punch them in face as hard as you can.

Exhibit number one for why I don't trust the media can best be summed up this way. They, from time to time, do a story on why people don't trust the media. And with a straight face, they act like it's a damned mystery.

This is also exhibit one for why I don't trust politicians. They act shocked that people think they're dishonest.

the media sucks god's evil cock and fucks holy Mary up the ass.

Wut?

"Why America Distrusts 'the Media'"

Because they are our enemies

' and What to Do About It'

Stop believing them

Stop supporting them

"What can be done? In an age when newspapers and other sources that at least aspired to be "objective" are declining, the future belongs to viewpoint-driven journalism. That isn't a bad thing, even if it means that "the media" as a general category might never regain the public confidence it had in the mid-1970s, when 72 percent of Americans told Gallup they trusted the press."

Low trust societies lead to violence and division. I am not so sure I see the silver lining in this like you do.

Not talking down to people who disagree with you requires patience, the ability to listen, and intellectual honesty.

People who have the qualities I mentioned are exploited by partisans who argue in bad faith.

Also, the Maddows are more annoying than the Hannitys. I don't know exactly why, but it's the truth.

This is why I hate liberal pundits more than conservative pundits. It's the cringeworthy levels of self-righteousness, the self-congratulatory circle jerk, the egos that make them compare themselves to firefighters.

Lately it is the complaints about how mean Trump is, and how brave journalists are; American TV pundits comparing themselves to war correspondents and journalists in Iran who are being executed for criticizing the government. It is insufferable.

There are two reasons why "media" aren't respected as news sources.

1) for a sunstantial portion of the population, they keep reporting facts that don't fit with the preferred ideology. Given a choice between rejecting facts, and rejecting ideology, most people discard the former rather than the latter, and, hey, might as well kill the messenger, too.

2) Quality journalism takes time, effort, and money. Bloviation sans facts takes none of these. You can have it right now, no need to wait until all the facts are in, and skilled bloviators can do it without even needing rehearsal. So, many sources cut costs by omitting all that tedious fact-gathering. People like it, so long as the bloviator tells them things they want to hear. People keep changing news sources until they get the bloviator that hits the things they'd like to hear, and avoids the things they don't want to hear (or even think about.)

Today's cable-news and pop-blog media also seem to exhibit a need to make themselves and their pet issues stars. There's a lot less reporting and a lot more promotion of themselves as the news. Whether that impulse comes at least in part from their bosses to boost ratings and clicks gobble up ad revenue, I can't say.

Rachel Maddow is the perfect example. She doesn't report, she lectures. She functions as a perpetually erupting crater of McCarthyist Russia conspiracy woo. Breathlessly, she spins preposterous and irrelevant trivia about Russian blah or blah into enormous spheres of editorial cotton candy. If you don't find Russiagate the most important story there is, or if you simply don't believe her diaphanous bullshit, she'll tell you right to your face with pedantic certainty that you're complicit in the destruction of democracy.

Russians pelting us with memes and ads has to be one of the least important non-stories ever. It ranks right down there with "a Kardashian is pregnant again" for the sheer lack of fucks most of America gives about it. And yet the media is almost angry with us for not caring more about their narrative. They aren't reporting: they're creating a story out of next to nothing and trying (and failing) to sell it. They might be more respectable if they knocked that shit off.

The most interesting part of this article is the chart that they stole from Politico. As the real difference between the two parties is exaggerated, I wonder what else could account for the increasing influence of solid-blue counties. Is the lion's share of the "journalism" in the northeast perhaps? Or are a handful of corporations the only ones left?

I'm shocked by the idea that anyone not paid to do so would voluntarily watch tripe like televised coverage of the White House Correspondents Dinner. I mean, watching paint dry is in the running with this...

" Now it's 2018, and readers can still fact-check journalists' collective ass. They will respond more favorably to those of us who make it easy for them by being upfront, honest, and responsive without having to be asked first."

Before 2018, the newspapers paid someone on staff to do their fact checking for them. It's not a trivial job and requires a professional touch. There was even a pension waiting for them when they retired. Expecting readers to do their own, time consuming, unpaid fact checking is hardly a step forward,

"Vulgarity is the lack of wit". Be careful who you choose as your entertainment.

"Random quotes are the lack of intelligence". Be careful of posting random quotes.

Fuck, I think we accidentally opened a wormhole.

Vulgarity is the spice of wit. Be careful thinking in platitudes.

Irony is universally lost on the ironic.

"Not misrepresenting opponents' viewpoints is a good a place to start..."

Has it not occurred to you, Nick, that journalists may be sincere in their belief that Michelle Wolfe's performance was just mean to folks sitting only a few feet away from her? Or that it was just mean?

"Physician, heal thyself," seems an appropriate bit of wisdom in this case.??

Many years ago I trusted the media pretty much but they are just shameless in their blatant political slant. Even though I have been a center right person politically they left me quite a while back now. I supported gay rights to marry but after the left succeeded with that issue they go right after letting trans persons serve in the armed services and of course the bathroom issue. Many millions of hard working, tax paying citizens do not support these issues and now we are called all kinds of names because we disagree with the left and those reporting the news.

Why America Distrusts 'the Media'

Because you constantly lie in exclusive service to one political party

and What to Do About It

Stop fuckin lyin

I had the impression our true father was leaving

There are sycophants, and then there are the True Believers. It was disgusting enough when the democrats were arranging devotional choruses of kids to praise the Teleprompter-in-chief, but this beyond pathetic.

-jcr

Objectivity has always been something of a con, since the selection of stories, of what counts as news and why, has always been hidden from view. So even a story that presents "both sides" can have an agenda despite its seemingly evenhanded approach.

This. There's simply no reason to trust them at all or to assume you are ever getting anything other than opinion.

Don't forget syntax. Writers choose nuanced words to describe issues which lead a reader down a positive or negative impression without ever making a factual statement at all. It's the very nature of language and should be resisted when reporting, but instead intonation and word selection is slyly evoked in article after article to propagandize or incite.

Lack of trust is appropriate. Cross referencing countervailing viewpoints seems the only way to go, which makes me draw the conclusion that only those who make the effort will be the ones not trapped in the morass of an ideological swamp, either progressive or conservative.

Remember when comedy was not "conservative" or "liberal" and generally was not about politics. I do. That was funny. Now not funny.

You have to be a complete moron to not acknowledge that the new is biased but also a complete moron to note that the liberal bias dominates the industry vs the conservative bias.

Nick seems to be a both sides do it type of guy. They do but one side does it quite a bit more. And one side is not content to the let the other side even speak. So the both sides argument is really weak.

The theme of the dinner was free speech and I guess Trump is a threat to that. How so? One the libby posters here give me an equivalent example of a lib speaker being cancelled. Something equivalent to banning Ben Shapiro because it's somehow "dangerous"

What to do about it? Please.

Never wrestle with a pig.

That's what to do about it.

Term limits for white house "correspondents". People are free to write whatever they want to, but press passes should not be a licence to fossilize in place.

The media institutions that are deeply integrated into the Washington DC political machine (including the "Brooklyn-based scribes" that Gillespie mentions) are simply going off the deep end in regards to eliciting emotional outrage over calculated reasoning and journalistic integrity. We now have headlines that include words like "creepy" ad nauseum, meant to appeal to humans' worst, most immature instincts. These media institutions have failed the American people, as they use the Trump presidency as a pretext to engage readers in a highly irresponsible, intellectually vacant, way.

It's a genuine problem. We can't expect Reason.com to get to the bottom of it though. Reason is supported by the Kochs and so there you go. Reason also thinks free markets can solve every social problem. I agree, CNN, MSNBC, etc. are biased and sucking up to the powerful. FOX, Bretibart, etc. do the same thing for their powerful supporters. The bottom line is that the media needs money to stay alive. You get money buy selling to customers. It's capitalism 101. Media will not criticize too hard anyone that would threaten to cut off their money supply. In a market-based structure that makes no sense. If reporters are self-interested then they know what stories to report on and which ones to ignore. Much of it is unconscious but it makes perfect sense.

There is no easy solution to this. I am not advocating government run media because we know that would be just as corrupt. The very fact that Reason.com won't acknowledge the structural problems of market-based new services just illustrates my point. It would piss off their funders big time. And besides, even if a reporter was critical of market-based media systems they would never get hired. The Koch's would threaten to cut off their funding.

Yes, people don't snipe at their own paychecks, but if we have a free market then what one doesn't cover another one will. Today's problem is that the government does indeed steer much of the media, and without much sunlight. I Recall one of Obama's favorite tools was to front run the AP before they got out of bed by leaking to Reuters in the UK, which provided a buffer and plausible deniablility to separate direct party communications from US based writers. There are other European methods I'm sure, as the geographic/time zone convenience is a force as sure as gravity. If NIxon were alive today... he would likely be green with jealousy, wishing he had done more of that. Anyone paying attention knows that most tv studios are severely cloistered and pretty much pick and choose from whatever the AP serves up in combination with favored prog "interest" groups like SPLC. I think its safe to say that there are only a handful of news rooms left that actually do real journalism anymore, and we can probably count them on one hand. Because of that void [and unbelievable sloth], most of our news gets written by the government by default. Why should news outlets do journalism when there are a dozen scripts handed to them every day?

I cut my cable... because the network tools should be paying me damages for their substandard/defective product.

Gillespie does mention journalists who don't belly up to the trough, though, or at least are still able to remain critical of their subjects: Greenwald and Spiers. So even in a market-driven media world, some journalists choose not to be slavering clickbait whores and lapdogs of the powerful, meaning that this is a choice. In fact, it can be a shrewd and profitable choice to remain critical of the political establishment, because if you're perceived by a market niche as a genuine, straight-shooting source of news, you'll have support.

Why America Distrusts 'the Media' and What to Do About It

Do about it? Why would I want to do anything about it. American distrust of the media is the best thing that's happened in decades.

" American distrust of the media is the best thing that's happened in decades."

But not as good as their distrust of each other.

As long as the perception is the media is the propaganda arm of the Democratic Party there's not going to be much trus

The media are owned by the 1% and used to brainwash the public into supporting their policies.

"Nothing that's happened in the last week will inspire more confidence that the press is comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable."

God, how I hate this canard. It is precisely this attitude that has poisoned the industry, as reporters work from a starting point of "afflicting" someone better off. Fuck that noise. Your job is to report what happened, when it happened, how it happened and, if possible, why it happened. Period. Your job is not to "afflict" anyone. Report the facts, and if they happen to afflict someone -- comfortable or uncomfortable -- so be it. Choosing who is to be "afflicted" is not part of your fucking job.

The media is not trusted because they no longer label editorial opinion as opinion, and because they do not report facts citing named, reliable sources.

What they can do about it is to label opinion as opinion, and cite named reliable sources for the facts they report.

See, simple. Not at all easy, but simple.

Fuck off, asshole.

Don't worry fuckbrain no one on this planet is interested in looking as retarded as you are by stealing your demented keyboard diarrhoea.

Fuck off, asshole.

Why are you defending a Welfare King who attacks everyone else's entitlements?

Are you too sucking the welfare tit?

Elilis Wyatt|5.4.18 @ 12:52AM|#

Why are you defending a Welfare King who attacks everyone else's entitlements?

Are you too sucking the welfare tit?"

Uh, try that in English, please.

Fuck off, asshole.

Mueller has the pee pee tapes in his possession and Trump will be impeached any day now!

All serious people who shit in their diapers at the nursing home realize this.

Fuck off, asshole

(smirk)

So now you're ashamed of defending somebody ..."who would cut his father's benefits .. and steal from his own kids, to enrich himself because he's ... ENTITLED .... and self-righteous."

Here again, I thought Michael Hihn was bat-shit crazy, but his link says exactly what he described.

So what's that make you?

No one is preventing you from jacking your flaccid 90 year old cock off to Michelle Wolf in between bouts of shitting your pants, they're just laughing at you.

It's funny that you think nobody knows you're sockpuppeting. You're the most pathetic waste of Medicare spending on nursing home space and Depends that has ever existed.

"So now you're ashamed of defending somebody ..."who would cut his father's benefits .. and steal from his own kids, to enrich himself because he's ... ENTITLED .... and self-righteous."

Here again, I thought Michael Hihn was bat-shit crazy, but his link says exactly what he described.

So what's that make you?"

O

M

G

Fuck off.

Dumbfuck Hihnsano and his multiple personalities.

Hahah wow this was pretty brutal.

So you are confirming that you are a psychopath?

Can't be mushrooms. Too... focused.

You're a real moron Sevo.

It's not right or left-winger, it's history. The Tet Offensive was a massive, debilitating defeat for the NVA and the Viet Cong. Instead of gaining ground, they lost ground, and suffered something like 40,000 fatalities, and however many wounded. The Vietnamese years later admitted that they thought the war was lost and that the US/SV would push it's advantage. It didn't, a tactical blunder that astounded the NV. It was a tactical loss for NV, but over time turned out to be a strategic win because...

In the US, Westmoreland had been saying in 1967 that the end of the war was in sight. The Tet Offensive, a major intelligence snafu on America's part, caught the US by surprise and put the lie to that. It led to Cronkite saying in Feb, '68, that it was likely the War in Vietnam would be a stalemate. Before he had some faith in what the US military said, after he was wary and critical.

The Paris Peace Accords were in Jan, '72, with direct US involvement ended by March with the pullout of American troops beyond an advisory capacity and supplier. For the US, the war ended in March 1973, with Nixon finally keeping his 1968 campaign promise.

The Fall of Saigon was April, IIRC, '75. That film is of that, not the US military being defeated by the NVA or VC and then scrambling for their lives.

Dumbfuck Hihpocrite screams while accusing others of screaming.

Dumbfuck Hihnsano is buttblasted that he's a moron no matter who he posts as.

Dumbfuck Hihnsano is pissed that He Majesty wasn't coronated!

Dumbfuck Hihnsano's IQ = Zero

Dumbfuck Hihnsano sees a liar when he looks in the mirror every day.

Dumbfuck Hihnsano projecting his pathologies.

Needz moar bold and capitalization

Dumbfuck Hihnsano and his copypasta.

The purpose of the Tet offensive was to get US television news to show NVA/Viet Cong troops in many major South Vietnam cities. It was never intended to be a military victory. The troops sent in had ammunition and food for three days. After that the survivors (if any) were to beat feet as best they

could. And the purpose was fulfilled. All the news was about how ol' Charlie was kickin' ass all over the South. Nothing about the number of troops being killed by US/South Vietnam troops, or about the actual military situation. And the US politicians fell into line and negotiated away the world, and proved the domino theory to be correct.