New Psilocybin Research Suggests 'Set and Setting' Are Crucial to Helping Patients Get Better

How patients feel on psilocybin has a huge impact on how they feel weeks and possibly months later.

Psychedelic researchers have known since the 1960s that bad vibes can lead to bad trips. Now researchers from the Department of Medicine at Imperial College London have published a paper providing new evidence that when it comes to psychedelic-assisted therapy, a positive "[mind]set and setting" may be crucial to long-term improvements in a patient's mental health.

Researchers David J. Nutt, Robin L. Carhart-Harris, and Leor Roseman wanted to test the hypothesis that "the quality of the acute [psychedelic] experience mediates long-term improvements in mental health." In other words, that feeling either good or bad while psychedelic drugs are active in the body determines whether patients experience improvement in symptoms weeks and months after undergoing drug-assisted therapy.

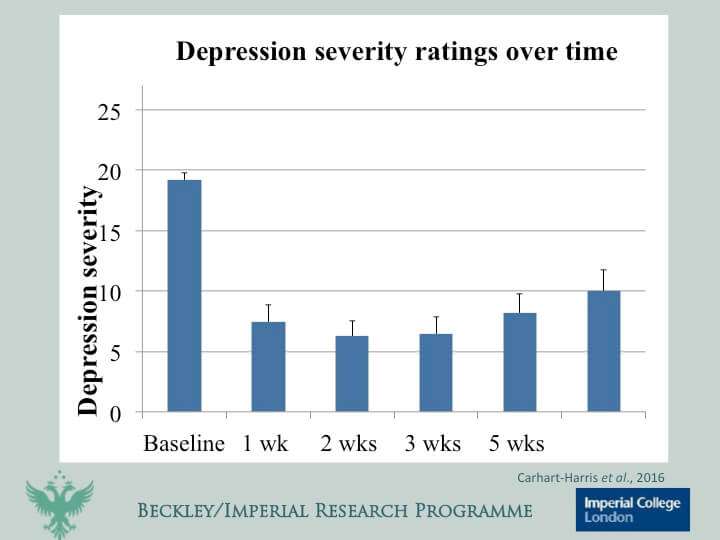

The Imperial team tested the question by administering psilocybin to 20 patients with treatment-resistant depression in a setting designed to produce a positive experience. They then administered the altered states of consciousness (ACS) questionnaire, which measures patient experience across several dimensions: 1. "oceanic boundlessness," Freudian shorthand for feelings of blissfulness, positivity toward other human beings, and oneness with the universe; 2. "dread of ego dissolution," which probes "negative, aversive experiences in which anxiety is a central aspect"; 3. changes in vision; 4. changes in hearing; and 5. receptiveness, or a lowering of the patient's guard.

Various forms of the ACS questionnaire have been used for years to get a sense of what, exactly, people experience when we use psychedelic drugs. The Imperial team decide to pair the ACS form with standard depression questionnaires. In this way they hoped to answer two major questions about the neurobiological mechanisms of psychedelic-assisted therapy: the extent to which visual and auditory changes impact clinical outcomes, and the correlation of negative and positive acute experiences with long-term mental states.

Five weeks after the study, nine of the 20 patients reported a greater than 50 percent reduction of depression symptoms. The team had replicated work done at Johns Hopkins University.

That's heartening, considering that depression is a miserable experience. But the really awesome finding here is the evidence that a positive acute therapeutic experience correlates with long-term improvement, while a negative acute experience does not:

This relationship appears to be somewhat specific, in that [a feeling of oceanic boundlessness] was significantly more predictive of positive clinical outcomes than altered visual and auditory perception—endorsing the moniker "psychedelic" ("mind-revealing") over "hallucinogen" when referring to this class of drug—at least in the context of psychedelic therapy. It also suggests that the therapeutic effects of psilocybin are not a simple product of isolated pharmacological action but rather are experience dependent. We also found that greater [anxiety and impaired cognition] experienced during the drug session was predictive of less positive clinical outcomes.

When I interviewed Roseman last year, he offered me this explanation for why a positive psychedelic experience could work as a form of medical therapy:

Ask a medical doctor, "What is PTSD?" and the answer they'll give is that it's a strong change in a person due to an experience. What you're trying to do with a psychedelic is reverse that change. You use the psychedelic to promote a certain experience, and that experience—not just the drug, the experience—is what causes the change. If you believe that a person can be altered by one bad experience, you should also be willing to believe that a person can change from one beautiful, cathartic, emotionally unitive experience.

The new study acknowledges that unaccounted-for components may influence outcomes more than, or as much as, the criteria in the ACS questionnaire. Music choice, priming, insights gained, and the relationship with the therapist may play a more important role than whether the patient felt a positive sense of connection and openness versus cognitive impairment, loss of control, and/or anxiety. While I suspect all of those things matter, my own experiences and the trip reports other psilocybin users have shared lead me to think that the team's findings will be replicated. Those other components, after all, are not mutually exclusive from the overall quality of a therapeutic experience. Feeling connected to, and safe with, a psychedelic therapist likely matters quite a bit in creating a positive acute experience. I would say the same of priming (i.e., mentally preparing the patient to have a good experience) and probably even music choice.

Another insight from this study is that psychedelic-assisted therapy is revolutionary for reasons other than pharmacology. In the U.S., primary care and family medicine doctors are playing an increasingly large role in recognizing and treating common mood disorders. In most cases, that amounts to administering a short questionnaire and prescribing an SSRI (perhaps in combination with bupropion) in the same 15-minute window those physicians would address any other common ailment. While it's probably better to have only a little attention rather than none at all, we are essentially moving away from an experiential therapeutic model in favor of assembly-line mental health care. Psychedelic-assisted therapy does not, and perhaps cannot, work that way.

Show Comments (8)