Seattle's Minimum Wage Killed the 'Five-Dollar Footlong'

Unfortunately, that's not all it's doing.

You probably remember Subway's famous "five-dollar footlong" promotion as much for the obnoxiously catchy jingle as for the sandwiches themselves. (Sorry for getting that stuck in your head all day.)

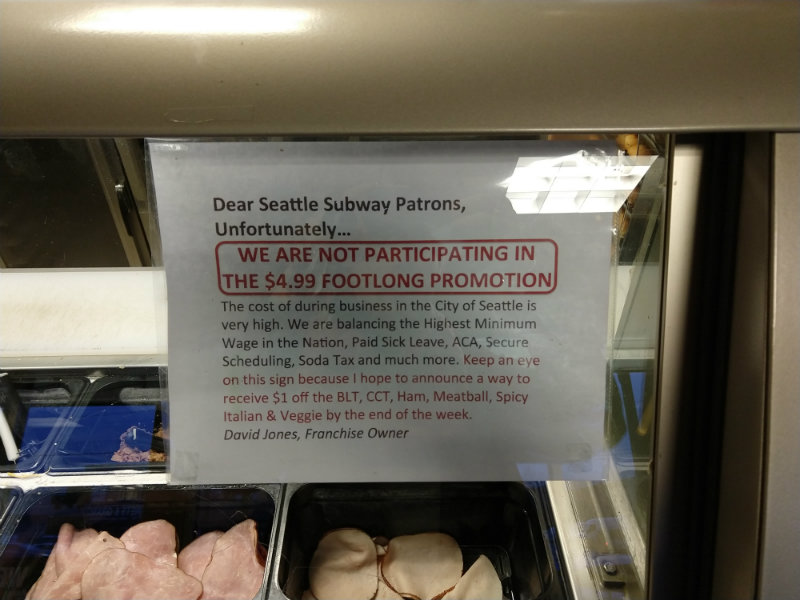

The sandwich chain recently resurrected the promotion in a national advertising campaign promising foot-long subs for just $4.99—but the special deal won't fly at one Subway restaurant in Seattle, where owner David Jones posted a sign this week giving customers the bad news.

Here's that sign, courtesy of Krisitin Ellis, an executive assistant at the Washington Policy Center, who tells Reason she spotted the dismaying sign yesterday afternoon while picking up a veggie footlong in the SoDo neighborhood:

Sadly, the consequences of high minimum wages, excessive taxation, and mandate-happy public policy are not limited to the death of cheap sandwiches. The cost of doing business in Seattle is higher than the Space Needle, and the unintended consequences of those policies are piling up too.

The biggest cost driver, as Jones' sign mentions, is Seattle's highest-in-the-nation minimum wage. It went from $9.47 to $11 per hour in 2015, then to $13 per hour in 2016, and to $15 per hour in 2017 or 2018 for most businesses, depending on how many employees they have.*

The result? According to researchers at the University of Washington's School of Public Policy and Governance, the number of hours worked in low-wage jobs has declined by around 9 percent since the start of 2016 "while hourly wages in such jobs increased by around 3 percent." The net outcome: In 2016, the "higher" minimum wage actually lowered low-wage workers' earnings by an average of $125 a month.

And now those same employees will have to pay more for sandwiches from Subway—and everything else too.

Compounding the misery is the city's new soda tax. By tacking another 1.75 cents onto every ounce of sweetened beverage purchased within the city, then-mayor Ed Murray promised, Seattle could subsidize trips to the farmers market, pay for free community college, and roll back "white-privileged, institutional racism." Racism has yet to disappear in Seattle, but as Reason's Christian Britschgi highlighted earlier this week, the tax has had the more immediate effect of hiking the price of a can of Coke by 20 cents, making a typical 36-can case of soft drink now $7.56 more expensive.

Kudos to Jones (who has spoken out before about the issues facing Seattle businesses, but did not return a call for this story) for being straight with his customers—and to other businesses, like this Seattle Costco, that have similarly refused to hide the costs of the city's soda tax from the consumers who have to pay it. In both cases, the businesses are looking out for their customers' best interests. Costco gave customers directions to another location outside the city limits where the soda tax would not apply, and Jones says he's trying to figure out a way to offer a discount on certain sandwiches, even if he can't afford to sell them for $4.99.

Seattle's city government might claim that it's looking out for workers' best interests by mandating higher wages and other benefits. But if the cost of doing business continues to climb, workers will be hurt, not helped. The end of the five-dollar footlong is likely only the beginning.

*CORRECTION: This piece was updated to better explain when the $15 minimum wage was implemented for Seattle-based businesses.

Show Comments (209)