The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

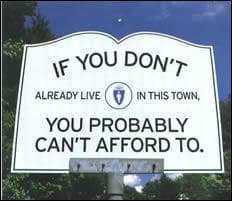

Expanding housing and job opportunities by cutting back on zoning

Harvard economist Edward Glaeser, perhaps the nation's leading expert on the economics of zoning, has an interesting Brookings Institution essay on how cutting back zoning can expand the availability of housing and job opportunities, particularly for the poor:

Arguably, land use controls have a more widespread impact on the lives of ordinary Americans than any other regulation. These controls, typically imposed by localities, make housing more expensive and restrict the growth of America's most successful metropolitan areas. These regulations have accreted over time with virtually no cost-benefit analysis….

America's affordability problem is local, not national, but that doesn't mean that land use regulations don't have national implications. Historically, when parts of America experienced outsized economic success, they built enormous amounts of housing. New housing allowed thousands of Americans to participate in the productivity of that locality. Between 1880 and 1910, bustling Chicago's population grew by an average of 56,000 each year. Today, San Francisco is one of the great capitals of the information age, yet from 1980 to 2010, that city's population grew by only 4200 people per year….

Land use controls that limit the growth of such successful cities mean that Americans increasingly live in places that make it easy to build, not in places with higher levels of productivity. Hsieh and Moretti (2015) have estimated that "lowering regulatory constraints" in areas like New York and Silicon Valley would "increase U.S. GDP by 9.5%." Whether these exact figures are correct, they provide a basis for the claim that America's most important, and potentially costly, regulations are land use controls….

Reforming local land use controls is one of those rare areas in which the libertarian and the progressive agree. The current system restricts the freedom of the property owner, and also makes life harder for poorer Americans. The politics of zoning reform may be hard, but our land use regulations are badly in need of rethinking.

There is substantial cross-ideological agreement among experts on these issues on the harmful effects of zoning. They have been decried by both free market economists and such of left of center commentators, as Paul Krugman, Matthew Yglesias, and Jason Furman, chair of Barack Obama's Council of Economic Advisers. Sadly, public awareness of the issue has lagged behind that of policy experts.

Glaeser outlines a strong case for limiting zoning. He also argues - correctly, in my view - that state governments are better position to address the problem than either the federal government or localities. He recognizes, however, that reform efforts will be difficult, because of strong interest group opposition, and lack of public awareness of the impact of zoning on housing and job opportunities.

I would add that reformers should challenge zoning regulations in court, as well as in the political arena. The Supreme Court's 1926 decision in Euclid v. Ambler Realty has long been interpreted to block nearly all constitutional challenges to zoning regulations under the Takings Clause, even though many take away major aspects of owners' property rights. But that doctrine is logically dubious, and in tension with recent cases strengthening Takings Clause protection for property owners against other types of regulations.

If a regulation can be a taking when it blocks development by forcing owners to subsidize construction elsewhere or by flooding or damaging the property in question, it is not clear why it cannot be if much of the value of the land is destroyed by categorically banning or severely restricting housing construction. In each case, the owner loses important rights traditionally associated with ownership, and the value of the property is greatly diminished. There is no basis in the text or original meaning of the Constitution for treating zoning restrictions differently from other land-use regulations with similar effects on property owners' rights.

If courts rule that severe zoning restrictions on building qualify as takings, that would not automatically prevent cities from enacting them. But it would require them to compensate landowners for their losses, which would help deter restrictive zoning by cities reluctant to spend large amounts of money to do it.

While it is unlikely that Euclid will be overruled anytime soon, it is possible that federal courts might restrict its reach. Similar results might be achieved under state constitutional takings clauses in many jurisdictions. State courts sometimes protect property rights (and other rights) under their state constitutions more strongly than is required by the federal Supreme Court's interpretation of the federal Constitution.

The odds of success would increase if the effort attracts support on both sides of the political spectrum. Increasing left-wing recognition of the dangers of zoning might lead some on the left to rethink the constitutional issues here, just as happened in the similar case of economic development takings, where many on the left opposed the Supreme Court's Kelo decision in large part because the sorts of condemnations it authorizes disproportionately harm the poor and minorities. The same is true of restrictive zoning, perhaps to an even greater extent.

Judicial review is unlikely to be the sole or even the most important tool in the struggle to reform zoning. But, as in many other situations, reform movements may have a better chance of success if they rely on a combination of legal and political action, rather than either alone. The civil rights movement, the feminist movement, same-sex marriage, the gun rights movement, and previous efforts to strengthen protection for property rights are all relevant examples.

I have previously written about the harmful impact of zoning on housing and job opportunities here, here, and here.

Show Comments (1)