This Son of Immigrants Fought For His Country While Rep. Steve King Dodged the Draft

The nativist Iowa congressman should have met my uncle before railing that you can't "rebuild civilization" with "somebody else's baby."

My Uncle Nick—my godfather and the man for whom I'm named—died last week at the age of 84. He was a really great uncle, brother to my mother and his other siblings, husband to his wife, and father to his daughters.

He was also, in the repugnant, nativist parlance of Rep. Steve King (R-Iowa), "somebody else's baby." That is, he was born to immigrants from Italy and thus, according to King and other xenophobes, incapable of helping to "restore our civilization." (For more on that, go here.)

Except that Nick Guida did make America a better place, first and foremost by being a good son, brother, husband, father, and uncle. He was a hardworking guy and even started his own business. He also served in Korea when called up to that bloodbath. (Steve King, in contrast, avoided service in Vietnam via college three college deferments even though he never actually graduated.) Nick's older brother, my Uncle John, served in World War II during the invasion of Italy, the very country his parents had left behind. My mother and my Aunt Lee, the only surviving member of her family, did their share to make America a better place, too, in all sorts of ways despite only learning English when they went to school.

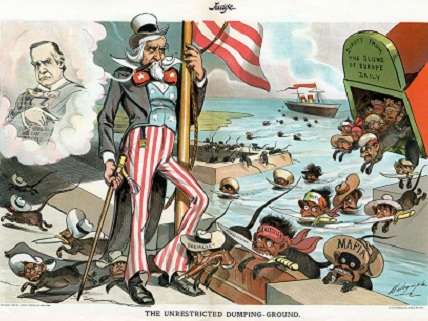

I don't want to waste much time just a couple of days before my uncle's funeral thinking about politicians, pundits, and demagogues who grotesquely dismiss whole groups of people who were, or are, "somebody else's babies." But for those of us who are within a few generations of being American, I think it's vitally important to remember how much our parents and grandparents were vilified for wanting to come here to create a better life for themselves and their children. In fact, my Italian grandmother, homesick for her family, traveled back to her birthplace with her oldest child and got locked out of America for several years due to immigration restrictions passed in the early 1920s. Like Mexicans and Arabs today, Italians were not considered desirable. In the 1890s, in the wake of a mass lynching of nine Italians accused of murdering the New Orleans chief of police, Theodore Roosevelt said the extra-judicial killings were "a rather good thing." A future governor of Louisiana proclaimed Italians as "just a little worse than the Negro, being if anything filthier in [their] habits, lawless, and treacherous." In reality, Italians in early 20th-century America had it much better than blacks, but it didn't mean they had it particularly easy.

Today's immigrants (legal and illegal) come from different countries than 100 years ago, but like those in the past, they start businesses at higher rates than natives, use less welfare, and cause less crime. Go ahead, look it up.

Despite the rhetoric of the Steve Kings and Donald J. Trumps of the world, immigrants and immigration are not antithetical to "making America great again" or, less dramatically, making the country a slightly better place than it was before my Uncle Nick was born. I won't be thinking about Steve King during Thursday's funeral, I'll be thinking about all the people my uncle helped during his life and how lucky we all were to know him. I'll be thinking, too, about my Italian grandparents, who never spoke English and yet somehow helped build this country nonetheless. And I'll be thinking about today's immigrants and children of immigrants, and hoping they get a fair shake in 21st-century America.

And maybe next week, I'll start thinking about what sort of arguments might actually help change the contemporary discussion about immigrants and immigration from one that is filled with anger and invective to one characterized by a sense of history and a willingness to talk about facts.

Show Comments (58)