Why Don't People Who Are Stuck in Depressed Appalachian Towns Just Leave?

A Reason writer returns to his family's home to investigate

I last visited McDowell County, West Virginia, over 40 years ago. Even then, I was already an outsider, a visitor to my family's past.

Sometime around 1950, my grandparents and all six of their grown children pulled up stakes and left McDowell behind. My grandfather bought a dairy farm 100 miles away in Clinchburg, Virginia, and my father joined him after he left the Air Force in the mid-1950s. The house I grew up in didn't have a bathroom until I was 5. My sisters and I bathed in a zinc washtub using water warmed on the chunk burner in our kitchen. Since our house was heated entirely by two wood-burning stoves, I spent a good portion of my summers chopping and stacking cordwood. My upstairs bedroom was unheated, so I slept in a cast-iron bed beneath three heavy unzipped U.S. Army canvas sleeping bags to stay warm. We got a telephone when I was 13 years old; it was a five-party line.

But it was the folks in McDowell—including many of my relatives—whom I thought of as poor. To my eyes, a huge number of the houses we drove past in hamlets like Squire, Cucumber, English, Bradshaw, Beartown, and Iaeger on our way to visit my father's hometown of Panther were little more than shacks. Many were covered with tarpaper. Indoor bathrooms and running water were luxuries. The houses that did have bathrooms more often than not simply ran a pipe from their sinks, tubs, and commodes directly to the nearest stream. My grandparent's old home was a nice and pretty spacious white clapboard house, but they got water from an outside hand pump and resorted to a first-class outhouse to answer nature's call. The water tasted distinctly of iron and sulfur. Except deep inside Panther State Forest, where the Bailey family held our annual Labor Day reunion, coal dust coated most buildings and automobiles.

I do not long for the chilly, dusty, impoverished life I remember—my experience of the past is whatever the opposite of nostalgia is—but in retrospect, I was witnessing the tail end of McDowell's golden era. Mechanization, especially the development of continuous mining machines, enabled coal companies to mine much more coal with many fewer workers. Out of a population of nearly 100,000 in 1950, 15,812 worked as miners. By 1960 that number was just 7,118. Today there are only about 1,000 employees working for coal companies in the county, out of a population of less than 20,000. The county's dwindling economic prospects were further devastated by massive floods in 2001 and 2002 that destroyed hundreds of houses and businesses and killed four people.

In recent years, McDowell has attracted attention for the worst possible reasons. It consistently shows up at the bottom of rankings, with the lowest levels of employment and the worst level of overall health in West Virginia, and the shortest male life expectancy in the nation. But it sits very near the top of lists of counties with the most drug overdoses, obesity, and suicides.

The rather unsentimental question I set out to answer as I made my way back this autumn: Why don't people just leave?

Bad News

One sign things are not going well in your county is when the kids in the social service programs know to do pre-emptive damage control with the press.

"Don't you focus just on the negative," warned Destiny Robertson, a spunky African-American senior at Mount View High School and a participant in the Broader Horizons program for at-risk kids devised by the Reconnecting McDowell task force. But it's hard not to focus on the negative when it can seem like that's all there is. Asked about their hometown, the kids shout out the usual list of woes with a world-weary attitude: bad schools, no jobs, drug addiction.

They're right to worry: McDowell County has been the iconic symbol of poverty in America ever since the 1960 presidential campaign, during which then–Sen. John F. Kennedy visited the county four times. In his May 3, 1960, speech in the town of Welch, Kennedy cited the collapse of employment in the coal industry and declared that had President Eisenhower "come to McDowell County, he would have seen a once prosperous people—the people of the largest and most important coal-mining county in the world—who were now the victims of poverty, want, and hunger."

Ever since, the unrelenting awfulness of McDowell's problems has drawn the eye of storytellers and researchers alike. In March 2014, The New York Times ran a story comparing affluent Fairfax County, Virginia, with McDowell. Besides noting the fact that average per capita incomes are five times higher in Fairfax, the article reported that average life expectancy in McDowell County was the lowest for males in the United States, at about 64 years. "Poverty is a thief," the Times quoted University of Maryland professor Michael Reich as saying. "Poverty not only diminishes a person's life chances, it steals years from one's life."

Right around when the New York Times writers rediscovered McDowell, Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton were uncovering an alarming new national trend: The mortality rates of middle-aged white Americans were increasing. In contrast, U.S. mortality rates have been steadily declining and average life expectancy increasing for well over a century. So what is going on with poor white people between the ages of 45 and 54? Case and Deaton reported in a September 2015 paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that nearly two-thirds of the increase in the white midlife death rate is the result of drug overdoses. Most of the rest is attributed to increases in suicide and chronic liver diseases like alcoholic cirrhosis.

McDowell fits that pattern: According to 2014 figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), it has the highest suicide rate in West Virginia at 22 per 100,000 residents, compared to a national rate of 13 per 100,000. The rate of liver disease in the county, which is the highest in West Virginia, is twice as high as the national rate, at 21 per 100,000 compared to 10 per 100,000. The number of murders per capita—again the highest in the state—is three times the national average.

Debra Elmore, who oversees Destiny's after-school program, backs her kids' generalizations with hard numbers that are hard to hear as well. "Ninety percent of kids in McDowell County schools are below the poverty threshold for free and reduced-price lunches," she says. "Forty-seven percent do not live with their biological parents, often because of incarceration and drug addiction, and 77 percent live in households in which no one has a job." And these bleak stats almost certainly understate the problem. Poverty numbers from the state, for instance, do not include children under 5 years of age.

The West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources reports that McDowell County has the highest prevalence of fair/poor health among adults in the state (25.3 percent), along with the second highest prevalence of obesity, with 44.8 percent of adults reporting a body mass index of 30 or above. The percent of residents over age 25 who are high school graduates is 64.5 percent; nationally, it's 86.3. Only 5.8 of residents have a bachelor's degree or higher, compared to the national rate of 29.3 percent.

In his incisive book, Hillbilly Elegy (Harper), self-described hillbilly and Yale Law graduate J.D. Vance notes, "Growing up around a lot of single moms and dads and living in a place where most of your neighbors are poor really narrows the realm of possibilities." He adds, "It means that you don't have people to show you by example what happens when you work hard and get an education."

Double Exposure

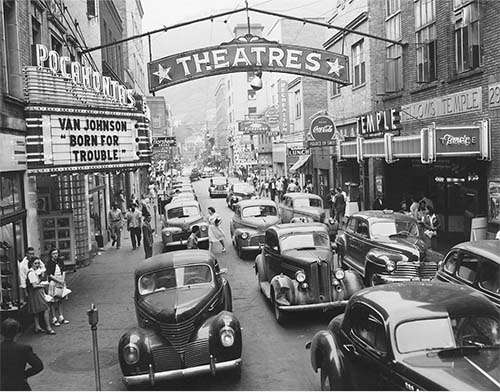

My grandfather and my Bailey aunts and uncles left McDowell County just as it was peaking economically and demographically. The county seat, Welch—a town of over 6,600 in 1950, located at the scenic confluence of Elkhorn Creek and Tug Fork River—was referred to affectionately by the locals as "Little New York." McDowell was then the leading coal producing county in the nation, until that honor passed to neighboring Logan County in 1955. Friday night traffic would be backed up two miles as coal miners and their families came to town for entertainment. In fact, traffic was so bad that Welch built the first municipal parking garage ever in the United States. A famous 1947 photo shows the main drag, McDowell Street, clotted with cars and crowds of stylishly dressed people eager to visit one of downtown's three famous movie palaces.

Today, the cineplexes are long gone (the Pocahontas burned down in the 1980s, perhaps due to arson) and the remaining buildings along McDowell Street are mostly empty.

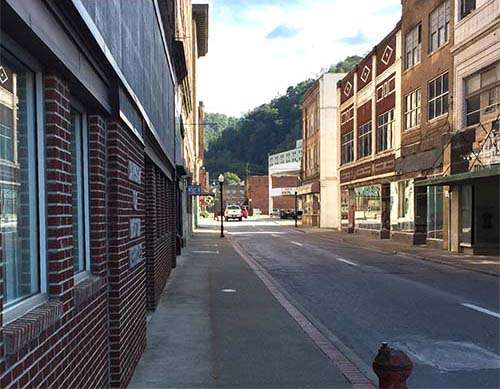

On the first afternoon of my visit, the only traffic was a lone pickup truck. Big, fine-looking brick houses built on the hillsides overlooking downtown and lining Stewart Street are relics from the prosperous past when King Coal reigned in these mountains. But the median home value in McDowell County is now $38,000, compared to $160,000 nationally.

I took a snapshot from the same spot as that mid-century photo 60 years later. It was a ghost town. The only commercial establishments still operating were a bank, two tiny drugstores, a gas station, and a three-plex movie theater. That parking garage still stands, but it's almost entirely empty. Most of the dilapidated buildings were abandoned or now house the extensive network of social services agencies that are meant to address and alleviate McDowell's many communal dysfunctions. Fewer than 2,000 people call Welch home.

Coal

Missy Hairston is a local girl who has made good. She grew up and went to school in McDowell County. As a teen-ager she participated in the African American Arts Heritage Academy summer program at West Virginia University (WVU) in Morgantown. She later majored in theater at WVU. "I

graduated in 2002 and I didn't even wait to get my diploma; I just took off for New York to look for jobs," she says when I bump into her in the office of state Delegate Clif Moore (D–McDowell). Hairston was in town from Los Angeles visiting her parents for a couple of weeks. "I am proud to be a coal miner's daughter," she says. "I came back because there is so much good here." She had stopped by to talk with Delegate Moore about how she might support arts education in the county's public schools.

A few minutes later her father, Mike Hairston, walked in. As we sat around the office, Moore prompted the elder Hairston to reminisce a bit. A proud member of the United Mine Workers union, he had worked 35 years on his knees underground mining 37-inch coal. He says that he'd never been hurt, never lost time due to an accident, and never been written up. He retired in 2003. Still, he acknowledged, mining is dangerous work. "You put your clothes on in the morning," he observes, "but you don't know who'll take them off of you in the evening."

Both Hairston and Moore muse about the bygone era of coal-fueled prosperity. "There used to be 10 car dealerships downtown in Welch," claims Mike. "Welch had three hospitals and three dry cleaners. The IGA, Kroger, Piggly Wiggly grocery stores are all gone. We used to have a train station and bus station. On Friday and Saturday you couldn't find parking in town."

"These coal companies put it to McDowell County. They made their money and then left us behind," he says, echoing a sentiment I heard many times on my visit. More than 93 percent of the land in McDowell County is owned by out-of-state companies, according to the Blueprint Communities report published by a community development nonprofit. (Disclosure: I am a partner in a family limited liability company that owns over 2,000 acres of land in McDowell.)

Both Hairston and Moore are convinced that the EPA is in fact waging a war on coal. Their complaints range from the agency's Clean Power Plan, which aims to cut greenhouse gas emissions, to its decision to review 79 surface mines' permits to see if they violate the agency's increasingly stringent regulations on how mining companies can dispose of waste rock. But they steadfastly refuse to blame President Barack Obama for what has happened to the industry.

Exports of U.S. coal have also fallen steeply, from a peak of 126 million tons in 2012 to just 28 million tons so far in 2016. Since 2011, the price of coal has dropped from nearly $150 per ton to around $45 per ton today. According the Bureau of Labor Statistics, employment in the coal mining industry in January 2012 stood at 89,800. As of May 2016, it has declined by more than a third to the current level of 56,600 jobs. The shale gas revolution made possible by fracking also played a big role. As power generators switched to cheaper and cleaner natural gas, coal consumption in the U.S. fell by 23 percent between 2008 and 2015.

All of which adds up to a dying industry with little chance of rallying in a town with no other industry.

Welfare

"The provision of subsidies to induce people to stay in…place delays the inevitable. At worst, such subsidies effectively retain the kinds of people who are the least able to adjust, ultimately, to market forces," write Iowa State University economists David Kraybill and Maureen Kilkenny in a 2003 working paper evaluating the rationales for and against place-based economic development policies. "It does no good to retain (or attract) people in places that are too costly for most businesses, which cannot sustain economic activity. That turns the place into a poverty trap."

McDowell is, in many ways, the perfect case study for this thesis. Chloe and Alderson Muncy of McDowell County became the country's first recipients of food stamps on May 29, 1961. The unemployed coal miner and his wife had 13 children at home. Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman handed over $95 in food stamps to the family, whose first purchase was a can of pork and beans from Henderson's Supermarket in downtown Welch.

Today, nearly 47 percent of all personal income in the county is from Social Security, disability insurance, food stamps (now known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP), and other federal programs, according to a 2015 report compiled by the West Virginia University Bureau of Business and Economic Research. Of the county's 19,800 residents, nearly 8,500 receive SNAP benefits, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

What McDowell County has is a surfeit of social services agencies and programs. So many, in fact, that Kathie Whitt, who is the executive director of Families, Agencies, Children Enhancing Services (FACES) is one of the leading figures in town. FACES does not provide any services, but it is the information clearinghouse for the more than 30 agencies and organizations that work on capacity building, economic development, child abuse prevention, drug prevention, pregnancy prevention, health initiatives, and organizational development. Whitt has been working with FACES for 16 years and is retiring this year. If all of the social services agencies in McDowell have a central planning commission, it's FACES. Whitt is the chief commissar, and I mean that in the best possible way. She's compassionately clear-eyed about the problems in the county.

"So many folks in McDowell have an entitlement mentality. Everybody owes them a living, housing, clothing, and food. They are the first ones who line up at every giveaway," she says. "Unfortunately that group is expanding."

Whitt worries about what will happen when the Baby Boomers step down from their leadership roles. "We have really seen some dark days," she says. "I do not feel that we have a good future based on where we are now. I think that McDowell County will continue to deteriorate."

Drugs

The state reported 79 drug poisoning deaths in 2015 in McDowell, and, owing to the prevalence of injection drug use, the number of HIV infections is the highest in the state. As background, the West Virginia Health Statistics Center reports that drug overdose deaths in the state increased from 212 in 2001 to 726 in 2015, while opiate-related deaths rose from 147 to 628 over that period. Whitt says that the Welch Community Hospital asks four questions of everyone being admitted to determine how at-risk they are for drug abuse. She claims that "80 percent of those coming through the hospital are positive for risk factors."

Based on her experience with social services, Whitt reckons that a high percentage of McDowell County residents between the ages of 18 and 40 are drug users and require a lot of assistance. "So many younger people in their 20s and 30s are strung out and walking around like zombies," she says. "They don't work and they don't raise their kids."

"It seems like parenting is a thing that people don't know how to do anymore," she continues. "Our parents taught us, but somehow the next generation didn't learn to be mothers and fathers." Again, the evidence is that about half the kids in the county are not living with a biological parent.

The faith-based Community Crossings agency tries to repair this deficit. Counselors offer in-home guidance to parents of young kids and throw "community baby showers." The goal is to reach people before they turn to the Department of Health and Human Resources, which funds and administers West Virginia's extensive welfare services. "A lot of the younger people don't have the mind-set to keep up with themselves," Whitt explains. "You see it in their houses, their cars, and their kids." According to a 2014 FACES report, McDowell County is 55th in West Virginia for child and family well-being, out of 55 counties.

"We don't see homelessness here like in D.C.," Whitt observes. "Instead, people sleep on someone's back porch kept warm by a kerosene heater or live in a camper van." She says she knows "five teens who are living out of backpacks moving from friends to friends right now." Whitt herself took in for several months a teen boy, a friend of her son's, whose father was abusive and mother suffered from schizophrenia. She eventually persuaded his uncle to take charge of him. The young man took a popular route out of the county by joining the military at 17.

"We have really seen some dark days," says Kathie Whitt. "I do not feel that we have a good future based on where we are now. I think that McDowell County will continue to deteriorate."

Donald Reed works nights at the Welch Hospital as a Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment drug abuse counselor. From that position he sees just how bad McDowell's drug, and especially prescription opiate, problem is. "McDowell has the second highest overdose rate in the nation," he says. I ask him if he's seen any cases in which addiction treatment worked. He sighs. "After 30 to 90 days at a treatment center, they bring you back to exactly where you were. People are so tied to their families," he explains. "When you come back to where you are comfortable, back to the same habits, and back to the same people, it's no wonder treatment hardly ever works." He adds, "There is no support here. The best thing you can do is leave here and never come back."

Drug addiction has also affected his family. Reed tears up when he shows me a photograph of his cousin Charlie, who died of an opiate overdose at age 20 while a student at Bluefield State College just 30 miles away.

Work

Even though the number of jobs in the mining industry has been declining for decades, it's still where McDowell residents turn when they think about employment. "This generation that is now coming along—they've got to go to school. A company that pays $9 million for a long wall mining machine is not going to put it in the hands of no one with no education," Mike Hairston says. Echoing a theme I heard from others, he adds that "most of the current generation is not qualified to do anything." Moore chimes in: "The unskilled, the unmarketable can't go anywhere."

According to the latest figures from the Census Bureau, 25 percent of McDowell County residents under age 65 are disabled, compared to 8.5 percent nationally. In addition, only 32 percent of residents over age 16 are in the civilian labor force, compared to the national rate of 63.5 percent. The median household income in McDowell is $23,607, compared to a national figure of $53,482; per capita income is $14,813 vs. $28,555. The Census Bureau reports that more than a third of residents are in poverty. Nationally it's 13.5 percent.

In January, Walmart closed its store at nearby Big Four, West Virginia, taking 140 jobs with it. "I never thought I'd ever say that I hate to see a Walmart close," Debra Elmore, the Reconnecting McDowell staff member, tells me. "But I do."

Various attempts have been made to jumpstart economic development in the county. One of the more notable was the creation, on an old strip mine, of the 5,900-acre Indian Ridge Industrial Park just north of Welch. So far the only "business" that has opened in the park is a federal prison, which started housing inmates in 2010. Indian Ridge is supposed to be strategically located along the route of the Coalfields Expressway, a long-delayed four-lane highway that would link McDowell to the Interstate highways. The hope is that the expressway will encourage business development by allowing drivers to bypass winding country roads.

One of the big problems confronted by McDowell County's schools is attracting and retaining teachers. Many commute from the more prosperous Mercer County next door. In fact, Whitt tells me 70 percent of the professionals, lawyers, doctors, and teachers working in McDowell do not live in the county. Interestingly, that includes Elmore. So the Reconnecting McDowell task force has cobbled together grants to build housing for teachers in downtown Welch on the site of an old furniture store. Right now the building site is a hole in the ground, but eventually it will have 28 to 32 apartments, communal spaces, and a coffee shop.

The vast majority of good jobs in McDowell are in government or nonprofit social services. According to the Blueprint Communities report, the public sector accounts for 33 percent of employment in McDowell County. The largest employer is the school board, and teacher salaries average just over $40,000 per year. Entry-level federal correctional officers earn $39,000 annually. That's considerably more than the median household income of $23,607.

Sorry

Beverly Slagle is a 73-year-old woman who is rearing two of her great-grandchildren, an adopted little girl, and a little boy of whom she has obtained custody. These legal arrangements are important because it means that Slagle, rather than her wayward granddaughter, receives the various social welfare payments to take care of the kids.

Slagle grew up in McDowell County but followed employment opportunities to other states. Her husband worked as a cement trucker in Ohio for 25 years and then took a job at a steel mill for three years in Michigan. After he became disabled, when a tank fell on him at the factory, they moved back home in 1982.

Asked why she takes care of her great-grandchildren, Slagle replies, "If we don't, who is going to take care of them? If we don't do it, social services will send them out of state." She says her granddaughter, now a 22-year-old home health care aide "on pain pills," has had three children by three different boyfriends. The newest baby lives with his father. The oldest was born when Slagle's granddaughter was 15 years old. "She's like so many young people today," Slagle says. "They are so sorry; they just don't want to do right. They stay on their phones and gadgets all day while their babies are doing God knows what.…Young people are not like when we grew up. Kids had chores then; now they only have gadgets to play with."

I ask FACES' Whitt why so many young unmarried women in the county become pregnant. She sighs and notes that birth control is freely available at school. Most of the girls and women are "on medical cards" (that is, enrolled in Medicaid) that would pay for contraception as well. It doesn't matter. "There are no consequences to pregnancy—they get immediate access to a medical card, food stamps, a check, WIC, and home visits," she explains. "They have all the welfare benefits as long as their kids are not adopted, plus there's no babysitting, since the grandparents will look after the kids."

FACES organizes a Second Time Around support group for folks who are raising their grandkids or great-grandkids. It meets once per month. Slagle notes that her friend and her friend's husband are raising two of their grandkids despite health problems. "Neither one of them is able to do it," Slagle says. "You know, if I weren't rooted here, I would take the kids and go."

Cold Turkey

So why don't people just leave? That question is actually surprisingly easy to answer: They did. After all, 80 percent of McDowell's population, including my grandparents, cleared out of the county to seek opportunities elsewhere during the last half-century.

But as the mines mechanized and closed down, why didn't the rest go, too? Reed, Whitt, and Slagle all more or less agree that many folks in McDowell are being bribed by government handouts to stay put and to stay poor. Drug use is the result of the demoralization that follows.

In a Fall 2014 National Affairs article called "Moving to Work," R Street Institute analysts Eli Lehrer and Lori Sanders asked, "What is keeping the poor from moving their families to new places to take advantage of better opportunities?" They argue that "the answer lies primarily in the structure of poverty-relief programs." In other words, the government is paying people to be poor.

Many of the 80 or so means-tested federal welfare programs that provide food aid, housing assistance, medical assistance, child care assistance, and other services for low-income individuals and families are administered by state agencies that each have differing requirements and standards. "For an individual or family faced with the stressful prospect of uprooting a household and leaving behind established community support systems, even a temporary loss of welfare benefits can be daunting," they argue. They conclude that "America's decentralized welfare state, in short, presents a major barrier to mobility itself."

Wouldn't the best option, then, be for Washington and Charleston to cut off the supply of public funds that generate so much heartache? Going "cold turkey" has its attractions, but it would leave a lot of human wreckage in its wake.

So is there another, less ruthless possible public policy response to the social pathologies afflicting places like McDowell? The R Street analysts' proposed solution to the mobility freeze is to streamline public benefits and provide some kind of subsidy to encourage people to move to areas with better job prospects. Perhaps by expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit, which is now only available to people with some income.

Stay

When asked about their future plans, the kids in Destiny's Broader Horizons group all say they hope to get more schooling. Most mention local institutions such as Bluefield State and Concord College, with the most distant being West Virginia University. The Reconnecting McDowell program, created by the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), aims to intervene in the lives of promising kids. One of the goals is to introduce students to the world outside of McDowell.

The group I talk with at Mount View High School are super-excited about the field trip to the Democratic National Convention they took. Because of the AFT connections, they received VIP tickets and got to watch Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton speak. "Just breathing the same air as President Obama was exciting," says senior Selena Collins. The group has also worked on a mural and attended a Lady Gaga concert. They make it plain that they were not at all intimidated by the size and hubbub of Philadelphia.

But when I ask if they plan to come back to McDowell County after they finish their educations, most say that they do.

Why? Mostly because of family.

Donald Reed, the hospital drug counselor, is someone who came back. "We can't sit here and wait for the government to save us," the 35-year-old says. "We can't sit here and wait for coal to come back." Reed's day job is as the West Virginia University Extension Agent for 4-H Youth Development. He works in the County Commission Building on Wyoming Street. The windows on the third floor of the municipal headquarters are boarded up with plywood, and signs on the way up direct visitors to the drug-testing facilities. Yet Reed has been quite successful, signing up nearly 800 kids for 4-H programs this year.

I ask him why people stay in McDowell. "People love it here," he says. "They love the safety of the mountains, the safety of small communities." As an example, he says that if his car broke down, it wouldn't be long before one of his neighbors driving by would stop to help him fix it or get him to where he needed to go. I suggest that it might take a bit longer for someone to stop and help me, an outsider. He smiles and allows that that might be the case.

But why did he stay? "I know there is very little opportunity here," Reed says. "But I wanted to come back because I need someone to remind me of what life is about. I know these people, prayed with them. They carried me when no else would. We value people, memories, and experiences."

I'm not entirely unsympathetic to the sentimental case for staying. At night, in my inn, I could hear the trains huffing up a grade so steep that the cars loaded with coal, grain, or manufactured goods from the Midwest are not only pulled by locomotives in the front but also pushed by locomotives in the back. The clatter in the dark reminded me of the trains that used to pass on the spur line from Saltville a couple of hundred feet behind the house I grew up in. It was an oddly comforting sound.

On my last day in McDowell, I drove to visit the site of past Bailey family reunions in the Panther State Forest, and to search for my grandparents' old home place in the town of Panther. As a kid, I hadn't really appreciated the awesomeness of the steep forested mountains flanking the narrow valleys through which Route 52, a.k.a. the Coal Heritage Highway, twists. Upon arrival, I spent a quiet moment swinging on the swings at the George's Fork picnic area. My attempt to find the old home place was not successful; the ragged road along the Tug Fork River is now lined with sagging trailers and tumble-down houses menaced by a luxuriant wilderness of kudzu vines.

But the broken beauty of McDowell isn't a good enough reason to stay when it comes down to it. It wasn't enough to hold my grandparents 60 years ago.

"If you get public assistance to supply your needs without any effort from you, you've got no incentive to better yourself or your situation," explains Reed. He reminds me that many of the people who remain in McDowell are there to help the people they see as family: "The only thing I ask of you when you walk away is to remember that not everybody here has lost hope. There is a group of people who are working to make things better." But in the end, he admits, "a lot of those who stay here stay here because they feel stuck."

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Stuck."

Show Comments (242)