Trump Has Little Latitude to Change Trade Policies…So Far

Bush and Obama tried tariffs, and got smacked down. But will a more determined protectionist rally legislators and public opinion to his side?

Over at Bloomberg Politics, Sahil Kapur has a useful piece detailing congressional unease at President-elect Donald Trump's recent rhetoric about slapping a 35 percent border tax on U.S. companies that offshore production and then try to sell their stuff back to America. In keeping with most coverage of Trumpian tweets, Kapur doesn't get to Question 1 of my 5-Step Process for Playing Defense Against Trump's Bad Ideas—What could President Trump actually do?—until paragraph 21:

Legally, Trump does have some unilateral powers to tax particular goods that cross the border, but not entire companies' products, said Gavin Ekins, a research economist at the right-leaning Tax Foundation. "In reality, a tariff doesn't quite work that way," he said. "But you can tax a class of goods. It's possible to say 'I'm going to put tariffs on heavy trucks within this time range.'"

Ekins said Trump will likely face legal challenges and may need buy-in from Congress and the World Trade Organization to make his plans stick. "He can technically do this but there's going to be push-back in many ways if he does," he said. "He's extremely constrained in what he actually can do in the very end."

Chad Bown, a senior fellow at the pro-trade Peterson Institute For International Economics, said Trump has broad authority to apply import restrictions under national-security exceptions, but he argued that going after entire companies' products would be "unprecedented" and could "backfire along a number of different dimensions." […]

He cited one example: "In 2009, the Obama administration imposed restrictions on Chinese tires. In response, they hit restrictions on U.S. poultry products, in particular chicken feet, a Chinese delicacy that we exported a lot of."

Trump wouldn't be the first president to unilaterally pursue protective tariffs.

In March 2002, for example, George W. Bush slapped tariffs of as much as 30 percent on steel imports to protect the ailing domestic industry, after his administration concluded that trading partners were engaging in predatory practices known as "dumping." The move faced international push-back, and 21 months later Bush abandoned the tariffs under threat of a trade war with Europe.

So even though Trump ran a far more explicitly protectionist campaign than Barack Obama did in 2008, he will be constrained by the Constitution, by U.S. law, international treaties, the potential for bilateral retribution (though he'd certainly be less gun-shy about entering into such conflicts), and by the GOP-led Congress. Kapur's piece, in fact, is largely a collection of hold-on-there quotes from congressional Republicans, such as House Majority Leader Kevin McCarty ("I don't want to get into some type of trade war"), Senate Foreign Relations Chairman Bob Corker ("I'm not much of a tariff-oriented individual"), and Rep. Jusin Amash (R-Mich.): "Maybe the slogan should be #MakeAmericaVenezuela."

So the question soon becomes, Might Congress change its mind?

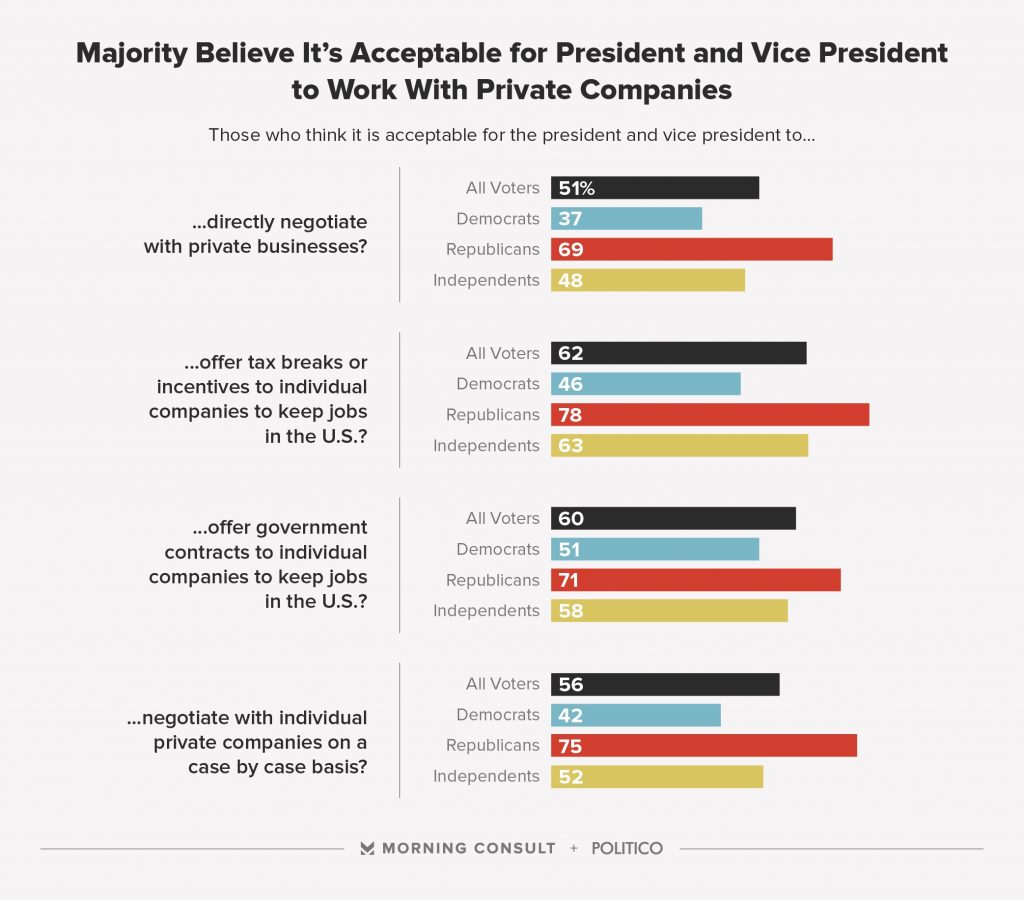

On the yes-it-damn-well-might front, comes this shock of a poll this week from YouGov, showing 57 percent of Republicans and 55 percent of conservatives (compared to 38 percent of independents and moderates, 33 percent of Democrats, and 31 percent of liberals) agree with Vice President-elect Mike Pence's appallingly inaccurate statement that "The free market has been sorting it out and America has been losing." The poll additionally showed that 73 percent of Republicans and 70 percent of conservatives agreed with "imposing stiff tariffs or other taxes on U.S. companies that relocate jobs," 78 percent of Republicans think it's proper to "offer tax breaks or incentives to individual companies to keep jobs in the U.S.," 75 percent of Republicans think it's Jim dandy for the federal government to "negotiate with individual private companies on a case by case basis," and 71 percent say it's fine to "offer government contracts to individual companies to keep jobs in the U.S."

As Allahpundit pointed out over at Hot Air, some of the partisan breakdown of these numbers can be attributed to the party that holds the White House (Democrats hated free trade during the George W. Bush presidency, for example). But still,

the share of Republicans who view free trade mainly as an opportunity hasn't been above 57 percent in the past 15 years. The number began to decline during the Bush years, in fact, not the Obama years, and was below 50 percent by 2008. The highest level it's reached since then is a mere 52 percent. For most of the past five years, there's been a double-digit gap between Democrats who see free trade mostly as an opportunity and Republicans who do.

Politicians, especially in the House of Representatives, respond to incentives. Yes, there are scores of pretty hardcore free-market types in the House GOP caucus, but their number used to include, among others, Mike Pence. Trump changing the calculus of how politicians can succeed in this country is certain to affect their choices.

Speaking of which, even if Trump will never get Justin Amash to sign onto a 35 percent punitive tariff, he might not have to, if he rallies enough Democrats to his side. As the president-elect's fellow NAFTA-hater Bernie Sanders recently tweeted, "If Trump is serious about helping the middle class, we'll work with him." Hillary Clinton, to name another prominent Democrat, ran commercials during the Olympics about punishing U.S. companies that dare relocate abroad. The idea is broadly popular, if economically daft.

When both major parties have officially lost their minds on a core economic issue, that can paradoxically lead to some dynamic possibilities amid the wreckage of realignment, though we are surely getting ahead of ourselves:

Now that Trump is a prime-the-pump Keynesian, the Democrats are going to go all Adam Smith on us, right?

— John Podhoretz (@jpodhoretz) December 7, 2016

The action in front of us right now is that congressional Republicans are trying to channel Trump's tariff enthusiasm into broader corporate tax reform they hope won't include tariffs per se (though it might occasion a pretty drastic overhaul of the way taxes and goods come in and out of the country). Tax reform is a sludgy business, so look for new President Trump to make some kind of targeted use of his tariff power, and then see how the public, the Congress, and the world reacts, probably in that order. Those who seek to forestall the re-escalation of global tariffs after a several-decades-long reduction have their work cut out for them.

Show Comments (46)