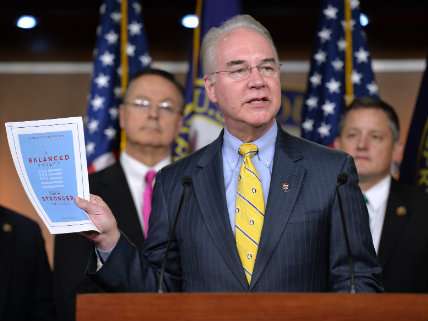

Trump Picks Tom Price For HHS Secretary. Does This Really Mean He Wants to Repeal Obamacare?

Ultimately, legislation to repeal and replace the health care law will have to be driven by Congress.

President-elect Donald Trump has picked Georgia doctor and House Representative Tom Price as his Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS). Price is an ardent critic of Obamacare, and also the author of one of the most detailed plans to replace the health care law. Since winning the election, Trump has appeared to waver on his promise to completely repeal the health care law, saying he might consider retaining certain provisions.

His choice of Price to oversee the sprawling federal health care apparatus is the strongest signal yet that the incoming president is firmly committed to opposing Obamacare—but it does not by itself guarantee that Republicans, who have long been wary of uniting around legislative specifics, will repeal or replace the health care law. And, along with a second pick to manage Medicare and Medicaid, it raises the possibility that Republicans will simply use the federal health bureaucracy to reward favored constituencies.

Aside from his consistent opposition to Obamacare, the most notable thing about Price is his own health care alternative. Unlike a lot of Obamacare critics in Congress, Price understands that on health policy, the details matter. When I interviewed him in 2013 about Republicans and health policy, he lamented the GOP habit of simply saying that Obamacare is bad law and declining to offer solutions of their own, and seemed frustrated by the lack of attention to particulars.

"Health care is complex," he told me at the time. "Most individuals kind of have their topline talking points. But if they're asked any questions beneath that veneer about the practicality or logistics of providing care and the consequences of whatever system you're recommending, it becomes very difficult to answer any of those questions in a normal talking-points kind of language…Once you drill down a bit, people become a bit uncomfortable."

Price, in contrast, has actually drilled down, a sign of his seriousness about tackling the challenges of U.S. health care policy. Many of the Republican replacement plans take the form of statements of principle or white papers. Price's plan, on the other hand, already exists in legislative form, as a 250-page bill known as the Empowering Patients First Act. The plan offers a level of detail that allows you to better imagine how it might work, and what sort of trade-offs it might entail.

The plan has a number of virtues, including its specificity, its emphasis on eliminating mandates, and its potential for massive reductions in federal spending. But it also comes with some risks and concerns, and, because Congress controls the legislative process, it may not prove the best guide as how Republicans end up treating health care in the Trump era.

Price's plan is focused on getting rid of a lot of the rules and regulations that make coverage under Obamacare expensive. It would eliminate the health law's essential health benefits rules—the list of mandates that require insurers to include a government-determined list of features, whether or not they're wanted. This would free up insurers to offer a wider array of types of coverage, and could help make coverage cheaper for many people, especially those who are in relatively good health and don't want or need comprehensive coverage. It would also allow for the purchase of health insurance across state lines to an even greater extent than already allowed under Obamacare.

Price's plan offers two mechanisms for sicker individuals who might be sicker and more expensive to cover: a provision that does not allow insurers to charge more for health conditions so long as someone maintains continuous coverage, and $3 billion in funding, over a three year period, for high risk pools. The continuous coverage provision is designed to encourage people to find insurance when they are young and then stick with it in hopes of creating a sustainable, long-term insurance pool—something that Obamacare, which has struggled to attract young people, has had trouble with so far. The $3 billion in funding for high risk pools—which comes to $1 billion a year—would help cover some of the hard cases, but may end up being too little for the job: Obamacare's high risk pools, which bridged the gap between when the law was signed and when its coverage provisions kicked in, ended up drawing a far more expensive patient pool than expected. And other Republican plans that rely on high risk pools estimate the cost at more like $2.5 billion a year.

Price's plan would result in a huge net savings to the federal government—about $2.3 trillion over a decade, according to a 2013 analysis by former Congressional Budget Office Director Douglas Holtz Eakin. So even with a significant increase in high risk pool funding, the plan would still represent a significant trimming of the country's budget.

There are, however, some real risks and worries to Price's plan as well. For one thing, it attempts to cut defensive medicine costs by offering legal protection to doctors who engage in best medical practices—which end up having to be determined by the federal government, or by some federally empowered board of medical providers. The potential for both bureaucratic sprawl and insider dealing with a system like that is high.

Price's plan also relies on the creation of voluntary purchasing associations designed to give bulk purchasing power to small businesses and individuals—basically by allowing them to band together to act as large organizations that can get the discounted coverage and preferential treatment enjoyed by large corporations. But the voluntary association model has been tried in several big states already, including Texas, California, and North Carolina, and it didn't work out. Those associations broke down as small businesses with healthier employees left the group to get even cheaper rates, leaving a pool of companies with sicker and more expensive workers.

Obamacare, of course, isn't just the private insurance market. A big chunk of its coverage gains comes from the expansion of Medicaid, the jointly run federal-state program for the poor and disabled. Price's plan would eliminate the Medicaid expansion entirely, with no replacement. That may have less impact than previously expected, however. As Brian Blase of the Mercatus Center noted yesterday, new research indicates that about two thirds of Obamacare's Medicaid enrollees were previously eligible—meaning they would have been able to get coverage without Obamacare, and would not be affected by repeal. Other Republican alternatives, like the Better Way plan championed by House Speaker Paul Ryan, would allow states to maintain the law's Medicaid expansion, but with somewhat reduced federal funding.

But today's personnel announcements may hold another clue as to how a Trump administration might treat Medicaid. In addition to Price, Trump also picked health care consultant Seema Verma to run the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which manages the two major health entitlements. Verma helped design and implement a Medicaid-expansion plan in Indiana under Gov. Mike Pence, who is now Trump's Vice President elect. That plan, touted as a market-based reform to Medicaid, was little more than a lobbyist driven deal to direct federal Obamacare money to the state's hospitals, even as Pence implausibly insisted that it wasn't really an expansion of the president's health law.

Indeed, the selection of Verma for the top slot at CMS may be more revealing than the selection of Price, because CMS is heavily and directly involved in negotiations over how states operate their Medicaid programs. Verma was involved in both the Pence plan and a previous Medicaid overhaul in Indiana under Gov. Mitch Daniels, a more defensible plan to integrate consumer-driven incentives into Medicaid. But especially with Pence in the White House, it at least raises a question about whether we can expect more lobbyist-driven, health care industry friendly deals in the future. And it suggests the possibility that we can expect the Trump administration to frame these deals as firm rejections of Obama's policies, even if they are not.

Because for all the details of Tom Price's Obamacare replacement plan, the Trump administration won't be crafting repeal or replace legislation. Instead, that process will be driven by Republicans in Congress, who have consistently failed to unite around a replacement plan, and have already begun to express some uncertainty about how much of the health care law they want to eliminate, and how long it will take to do so. Sen. Lamar Alexander, who as Chair of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee is likely to be a key player in any GOP replacement effort, recently said that it might take six years to draw up a replacement plan—not mentioning that Republicans have been promising to deliver a replacement plan for about that long already, but have failed to unify around a plan.

A Trump administration could take some significant actions on its own, speeding up the decay of the health law's exchanges by stopping some of the legally dubious payments that the Obama administration has been making to insurers. But even a complete disintegration of the marketplaces would still leave Obamacare on the books, without any replacement.

The administration, for all its power, can't drive the repeal and replace process entirely on its own. So Price's nomination is a signal and a symbol, arguably a rather important one, of the Trump administration's opposition to the health care law. But as Price himself knows, symbolic statements of opposition aren't enough. Fully repealing and replacing the law will require actual legislative action, which means debating and agreeing on the details—and so far that's something that many Republicans in Congress have not been willing to do.

Show Comments (159)