How Idaho's Drug Warriors Stole Hope from Epileptic Kids

A Reason investigation uncovers how cops, prosecutors, and lobbyists conspired to restrict a promising cannabis-derived seizure treatment.

In December 2014, Josh Phillips' mother answered the phone to news no parent wants to hear. Her son, an epileptic high school senior and champion wrestler, was in the hospital.

The whole Salmon High School wrestling team was waiting at Steele Memorial Medical Center when Jeanette and Gary Phillips got there. The team had been on its way home from a match at West Jefferson High, more than an hour away and out of cellphone range in the rugged backcountry of northeastern Idaho, when Josh Phillips suffered the worst seizure of his life.

As the bus raced back to Salmon, Josh went in and out of consciousness. He stopped breathing at least once.

"We thought we were going to lose him," recalls Jason Bruce, the team's coach.

Josh had been diagnosed with epilepsy when he was 10 years old, but he'd been wrestling since he was much younger, following in the footsteps of his father and older brother. Josh was the best of the bunch. He'd never been pinned during his four years at Salmon High, and Bruce says Josh was a clear favorite to win the state championship at the end of his senior season.

He never got the chance.

After a frantic drive through the mountains, Bruce was finally able to call an ambulance to meet the bus and Josh made it to the hospital where he was stabilized. But the incident on the bus forced the school's hand, and the decision was made that Josh would no longer be allowed to travel with the team. It was too dangerous.

Now, instead of dreaming of a championship, Josh is just hoping for a normal life. He's tried more than a dozen different medications and even underwent brain surgery. But the seizures that denied him a shot at a state title now prevent him from pursuing even the most mundane goals of the average 19-year-old. He can't go to college and probably won't be able to move out of his parents' house. He's not allowed to drive a car, and won't get permission until he can show doctors that he's having less than one seizure per month.

With pharmaceutical and surgical treatments unsuccessful, the Phillips family and others in Idaho placed their hopes in the legalization of cannabidiol oil, or CBD, a form of medical marijuana. Though not guaranteed to work for everyone, CBD has been shown to be effective in controlling seizures in some epileptic patients. For that reason, it's been legalized in dozens of states as a medical treatment, including many states where more widespread uses of medical marijuana remain banned.

In Idaho, a bill to allow people like Josh Phillips to access CBD oil was passed by the state legislature in 2015, only to be defeated by a group of powerful special interests—including cops, prosecutors, and pharmaceutical companies—with direct access to policy makers in Boise. Emails obtained by Reason reveal a behind-the-scenes effort organized by the state's Office of Drug Policy to derail the CBD legislation and, after it passed against the wishes of Gov. Butch Otter and his administration, to use executive authority to replace the bill with an alternative treatment program that has done nothing to help Josh Phillips or many other Idahoans suffering from seizures.

In the middle of it all was a governor who had for years professed support for ending drug prohibition, only to turn his back when the opportunity came.

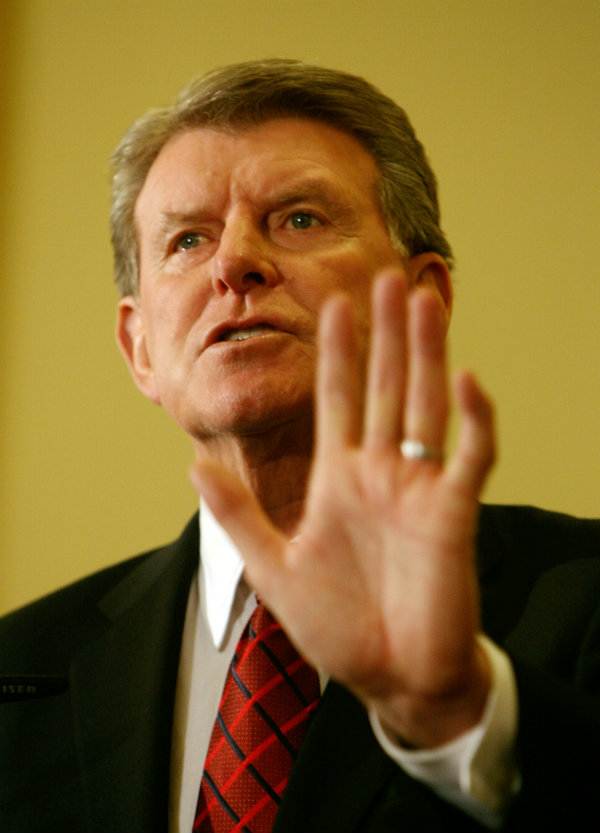

Butch Otter: A History Of Supporting Pot Legalization

Nearly 20 years before Josh Phillips was born, Clement Leroy "Butch" Otter was already pushing for marijuana to be legalized in Idaho.

In 1978, the future governor was a 35-year-old two-term state lawmaker who was running as something of a radical upstart in the state's gubernatorial election.

"If a person, of his own free will, wants to use marijuana, I question whether the government has any propriety in telling him he can't." —Butch Otter

"If a person, of his own free will, wants to use marijuana, I question whether the government has any propriety in telling him he can't," Otter told Reason that year. "The government, in effect, is taking away the only real gift the Lord gave us."

Intentionally or not, Otter was suggesting that socially permissive policy choices were compatible with—and perhaps even logically following from—a worldview informed by Christian religious tradition. Free will demands that people be allowed to go their own way, take their own risks and make their own mistakes. That's a perspective that fits with Idaho's religious conservative culture—and one that runs directly against any notion of government-enforced prohibition.

Otter lost his first gubernatorial race in 1978, finishing third in a seven-way GOP primary. But he won his next race, for lieutenant governor in 1986. He would win re-election to that post three times before earning a seat in Congress in 2001.

As lieutenant governor and during three terms as the representative from Idaho's First Congressional District, Otter developed a reputation for being a free thinker with a high degree of skepticism toward government power.

In 1987, Democratic Gov. Cecil Andrus left the state to attend a conference, leaving Otter to serve as acting governor. While in that role, Otter vetoed a bill that would have raised the legal drinking age in Idaho from 19 to 21 in order to allow the state to access federal highway funds. He said the bill was tantamount to giving into federal blackmail.

Starting in 1999, Otter fought a two-year personal battle with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) after being cited for building an illegal pond in his backyard. The EPA said he was disturbing a protected wetland, but Otter maintained that he was allowed to do as he pleased on his own property.

In Congress, he gained notoriety for being one of three Republicans—along with Ron Paul of Texas and Robert Ney of Ohio—to vote against the PATRIOT Act in 2001.

In 2006, after three decades in politics, Otter found himself back where he started: campaigning for governor and talking to Reason magazine about why Idaho should legalize marijuana, at least for medical purposes.

"I still support medical marijuana," Otter said in 2006, just weeks before he was elected governor. "Some of these people, the only way they can get relief is by smoking marijuana."

Nine years later, after winning a third consecutive term as the state's chief executive, Otter finally had a chance to put his name on a law that would legalize, for the first time in the state's history, a form of marijuana to treat medical issues like seizures. The bill was SB1146.

He vetoed it.

The Promise of CBD Oil

More than 3 million Americans suffer from epilepsy, and about one-third of them have a form of the disease that does not respond well to pharmaceutical treatments.

That includes Josh Philips. Since his childhood diagnosis, Josh has tried 15 different epilepsy medications with

various degrees of success. Some of them work for awhiles and then stop working. Others never work at all. At worst, the side effects—nausea, mood swings, and dizziness, among others he can rattle off like he's permanently stuck inside the last 15 seconds of a televised drug advertisement—are as bad as his seizures. "They just wear you out," he says.

In early 2015, Josh first read about how cannabidiol oil, or CBD oil, can be used to treat seizures like his. Made from the stalks of the cannabis plant—as opposed to coming from the flowers, or "buds," of the plant like other forms of marijuana—CBD oil lacks high levels of tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC. So even though CBD is still a psychoactive drug that alters how the brain functions, it does not produce the same feeling of being high that comes from smoking or eating cannabis products with higher concentrations of THC.

Around the same time, state lawmakers in Boise were also looking into the substance. That spring, the Republican-controlled state legislature crafted and eventually passed Senate Bill 1146. The bill would have strictly controlled THC levels, allowing only CBD oil that contained less than 0.3 percent THC, and possessing CBD oil would have been legal only with the written permission of a licensed physician. In turn, physicians would only be allowed to prescribe CBD oil for the treatment of intractable seizures that had not responded to other treatments. The 0.3 percent TCH limit is the same standard used by several other states that have legalized CBD oil while keeping marijuana derivatives with higher levels of TCH illegal.

"You could drink gallons of the stuff and not get high," says state Sen. Jim Rice (R–Canyon), one of the bill's co-sponsors.

Rice is opposed to legalizing marijuana. But input from neurologists who work with epileptic patients convinced him to get behind the bill, and he says it was written to prevent CBD oil from being abused as a drug. "Intractable seizures are tough—one of those things where you have parents who are just hunting around trying to find something that will work for their kid," he says. "If this works, it's life-changing."

The question, though, is if it works. Federal restrictions on marijuana research mean that there is no conclusive evidence to show that CBD is an effective treatment. But there is a growing body of anecdotal evidence that, at least for some people, CBD oil can bring intractable seizures under control.

The American Epilepsy Society (AES) says that the limited scientific evidence for marijuana treatments does not mean CBD is ineffective, but that more research is needed to prove its usefulness. To that end, the group has called for marijuana to be removed from the federal Schedule I list, a set of drugs considered by the Drug Enforcement Administration to have "no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse," including heroin, LSD, and ecstasy.

Citing Law Enforcement Objections, Otter Says No

Unlike Rice, Otter wasn't convinced. Ten days after the CBD bill passed in the House, the governor issued his veto with a message scolding the legislature for passing the bill against the wishes of the state's law enforcement special interests.

"I don't know what more I or senior members of my administration could have done to help legislators understand our strong opposition to this legislation," he wrote in his veto message. "Both the House and Senate were told by the Office of Drug Policy, the Department of Public Welfare, and the Idaho State Police—as well as prosecutors and local law enforcement officers throughout Idaho—that there were too many questions and problems and too few answers and solutions in this bill to let it become law."

Forced to choose between the families and children who wanted CBD oil legalized and the opposition from law enforcement, Otter chose the latter—though he said he "sympathized with the heartbreaking dilemma" facing Idahoans dealing with debilitating diseases that could potentially be treated with CBD.

Jon Hanian, Otter's spokesman, says the governor stands by the veto. Asked how that decision squares with decades of professed support for marijuana legalization, Hanian said Otter admits to changing his position.

"In the decade since he was last quoted [in Reason], he has seen the problems other states have experienced since legalizing marijuana," Hanian wrote in an email. "He has heard stories from some of his colleagues in the Western Governors Association about how legalization, in their states, is not the panacea they first thought it would be." One governor, Hanian said, "went so far as to suggest that it was a mistake."

Hanian did not respond to repeated requests for the identity of the governor who regretted legalization. But one possibility is Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper, who called marijuana legalization in his state "reckless" when it was approved by voter referendum, which did not require his signature.

Hickenlooper has reconsidered that opinion over the past three years and now says legalization is a success in his state.

Other Republican Governors Have Approved CBD Bills

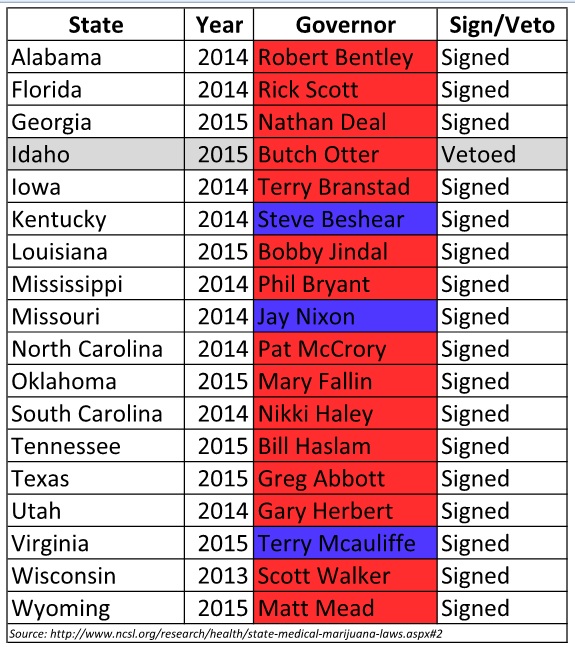

Otter's veto represents more than a break from his own decades-long support for marijuana legalization. It also makes him an outlier among his peer group of Republican governors in conservative states.

Less than three months after Otter vetoed SB1146 in Idaho, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott signed a bill legalizing low-THC cannabis oil for the treatment of epileptic seizures in his state. Like the bill in Idaho, Texas' CBD oil law requires a prescription from a neurologist or an epileptoloigist. Even as he signed the bill, Abbott reiterated his opposition to broad-based marijuana legalization.

"I remain convinced that Texas will not legalize marijuana, nor should Texas open the door for conventional marijuana to be used for medicinal purposes," Abbott said, according to The Texas Tribune. "As governor, I will not allow it."

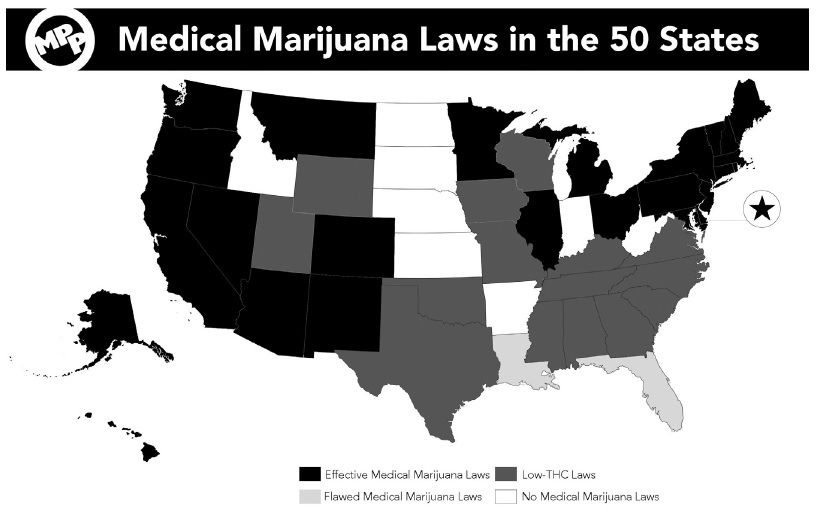

When it comes to parsing the difference between CBD oil and medical marijuana, Abbott is hardly alone. Since 2013, 17 states have legalized low-THC cannabis oil for limited medical purposes. Republican governors have signed 14 of those bills, including governors of deep red states like Alabama, Mississippi, South Carolina, and even Utah.

Despite the powerful influence of social conservatives and a state legislature that is 82 percent Republican, Utah passed a CBD oil bill with near-unanimous support. It was signed into law by the state's Republican Governor, Gary Herbert, in March 2014.

In fact, Otter is the only governor to veto a CBD oil bill, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, which tracks legislation proposed and passed in states.

The Cops Did It

In his veto message, Otter explained his decision by warning of "the potential for misuse and abuse with criminal intent." He cited the lack of support from Idaho's law enforcement groups, and said that legalizing CBD oil could "decrease public safety," without explaining how.

The law enforcement community's own explanation for its opposition wasn't any better.

"It basically opens the door, carte blanche, to make it almost unenforceable for us to be able to stop marijuana or illegal drugs in our communities," said Shane Turman, president of the Idaho Chiefs of Police Association, at a hearing of the state Senate State Affairs Committee concerning the CBD oil bill in March 2015.

"The bill is the most liberal CBD bill in the country," declared Bryan Taylor, president of the Idaho Prosecuting Attorneys Association, at the same hearing. "There are no regulations or safeguards."

Rice, the Republican legislator who sponsored the CBD legislation, sees things differently. He says the state legislature worked with law enforcement to rewrite parts of the bill in an attempt to address those concerns. The final version of the bill would have required written permission from a doctor before a patient could obtain CBD oil and allowed doctors to prescribe CBD oil only for the treatment of intractable seizures after other medical options had been tried. There was nothing in the CBD bill that would have prevented police from arresting anyone for illegally obtaining or using marijuana or marijuana-derived products.

Instead, it provided what is known as an "affirmative defense" against prosecution for possessing an otherwise illegal substance. That means police officers, and drug dogs, would still be able to bust marijuana users. Anyone who had obtained the CBD oil with the permission of his or her doctor, however, would be protected against prosecution.

While the legislature worked to address some of the law enforcement lobbyists' concerns, representatives from the Idaho Prosecuting Attorneys Association, the Idaho Chiefs of Police Association, the Fraternal Order of Police, and other "law enforcement folks" were meeting with Elisha Figueroa, director of the Idaho Office of Drug Policy.

Figueroa served as a conduit for law enforcement efforts to torpedo the CBD bill. In one email to Otter's chief of staff, she notes that she'd been "working tirelessly all session to oppose" the bill.

Officially, the Office of Drug Policy is tasked with "providing policy, education, prevention and treatment resources" and works toward "an Idaho free from the devastating social, health and economic consequences of substance abuse" by funding anti-drug initiatives and overseeing substance abuse programs. Politically, the office serves as a nexus for the various special interests that favor the status quo of drug prohibition in Idaho, giving them a special place within the apparatus of state government.

During the CBD oil debate in 2015, Figueroa, who was appointed by Otter to run the office in 2012, served as a conduit for the law enforcement groups' efforts to torpedo the bill. In one April 2015 email to David Hensley, Otter's chief of staff, obtained by Reason, Figueroa details how she had been "working tirelessly all session to oppose" the CBD bill.

In that email, written four days after the bill reached Otter's desk, Figueroa's became even more adamant about derailing the legislation.

"With no hesitation I will tell you that the criminal element in this state will use this law to disguise their illegal drug activity," wrote Figueroa. In the same message, she tellingly asked for the opportunity to let lobbyists write a better version of the legislation. "If Idaho is going to open this door, please allow me the opportunity to bring stakeholders together and do it correctly," she wrote.

Her work appears to have paid off. Six days after her plea, Otter vetoed the bill. In his five-paragraph statement about the veto, he twice pointed to opposition from the Office of Drug Policy as reasons why he would not sign it.

Figueroa says members of law enforcement and their lobbyists were concerned about the CBD oil bill. Since part of her job is "to determine how the health and safety of Idahoans may be affected by legislation," Figueroa wrote in a November 2016 email to Reason, "it's not unusual for me to discuss pieces of legislation or legislative ideas with those community stakeholders who would be affected by such."

The effort to "bring stakeholders together," she says, was a reference to "agencies that would be affected by the bill or would be responsible for implementing new programs or procedures as a result of a new law."

Whether under the influence of lobbyists or not, Figueroa undoubtedly held considerable sway within the Otter administration regarding the CBD legislation. As we will see, that influence not only helped give voice to law enforcement concerns about the bill, but also guided Otter's decision to implement a clinical trial of a new pharmaceutical drug instead of legalizing CBD.

Big Pharma Steps In

If we take Otter at his word—and the word of his spokesman—then it was law enforcement's opposition to the CBD oil bill that convinced the governor to veto it, and general concern about the public safety consequences of legalizing marijuana that convinced him to change his long-held views on the topic.

There may have also been a second factor pushing Otter's administration to oppose the bill and favor a clinical trial of a particular drug instead.

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers Association, or PhRMA, represents drug companies and lobbies on their behalf. According to federal lobbying data aggregated by Maplight, PhRMA has spent more than $150 million on lobbying since 2008—a total that only includes federal advocacy efforts, not similar work done in state capitals.

But Big Pharma is active in the states too, and drug companies have been particularly keen on fighting efforts to legalize medical marijuana in all its various forms, including CBD oil.

That's because states with legal medical marijuana have lower rates of drug prescriptions. In a study published earlier this year, Ashley and W. David Bradford, a daughter-father pair of researchers at the University of Georgia, analyzed state-level prescription drug databases from 2010 through 2013 and found that doctors prescribed significantly fewer pharmaceutical drugs in states with legal medical weed. The largest drop-off was for prescription painkillers, with 1,800 fewer doses prescribed annually in states with medical marijuana laws. They found a significant decline—486 fewer doses annually—in prescriptions for anti-seizure drugs as well.

In Idaho, PhRMA employs two full-time lobbyists to influence public policy. It also spends lots of money helping to elect state lawmakers from both sides of the aisle—including Otter.

Otter got two maximum contributions from PhARMA in 2014—one during the primary campaign cycle and another during the general election campaign cycle—as he was running for a third term.

Since returning from Congress to run for governor in 2006, he's received $22,500 from PhRMA—that's 23 percent of the money the association has spent on campaigns in the state in the last 10 years, according to campaign finance records. Contributions are capped at $5,000 per cycle under Idaho campaign finance law, and Otter got two maximum contributions from PhARMA in 2014—one during the primary campaign cycle and another during the general election campaign cycle—as he was running for a third term.

In context, a $10,000 contribution is not a ton of money. Otter raised more than $2.2 million from 4,800 contributions during the 2014 election cycle. Still, the average donation was a mere $490, and maxing out its contributions would likely keep PhRMA's interests on Otter's radar, ensuring the governor would open his door to the organization's lobbyists if they wanted to talk.

So pharmaceutical companies had a motive (fewer prescriptions issued in states with medical pot) and means (campaign contributions and lobbyists) to influence the Otter administration's decision on SB1146. Did they have the opportunity?

Hanian, Otter's spokesman, says they played no part in the decision-making process. "The governor met with a wide cross section of individuals on both sides of this issue, including many of the individual families dealing with this disease," he wrote in an email. "Lobbyists did not factor into this decision."

An email obtained by Reason via an open records request, however, reveals that Figueroa reached out to Jeremy Pisca in early January to discuss "the Office of Drug Policy's work on the CBD oil issue." At the time, Pisca was working as a contract lobbyist for the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturing Association, according to a state lobbying database.

"Tammy [Perkins, the governor's senior special assistant for health and social services] mentioned that she spoke with you a bit today about the Office of Drug Policy's work on the CBD oil issue," Figueroa wrote. "Maybe we could meet for lunch?"

There was no written response from Pisca—at least not one copied to Tammy Perkins. Figueroa, in an email to Reason, admitted to contacting Pisca but said he did not respond to that request. A records request for Figueroa's emails has not been returned and Pisca did not respond to requests for comment.

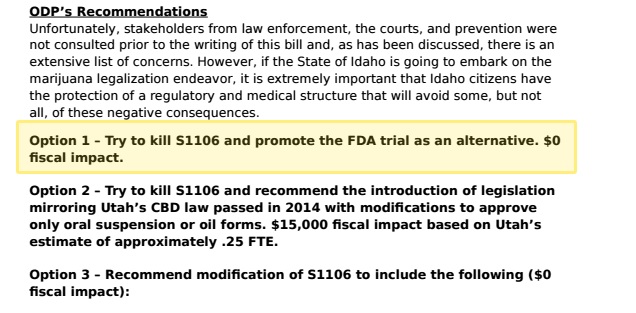

But a month after reaching out to Pisca, Figueroa was trying to steer the state legislature and the Otter administration toward an alternative to CBD oil legalization: a limited clinical trial of a new drug. In a primer sent to Perkins on February 27, Figueroa outlined three potential outcomes for the CBD bill. The "preferred option," she wrote, was to "try to kill" the CBD bill "and promote the [Food and Drug Administration] trial as an alternative."

The timeline suggests that the Office of Drug Policy was never really working with the legislature to pass a mutually agreeable version of the bill, but was moving on a parallel track from the start.

On March 4, in testimony to the Senate State Affairs Committee, Figueroa suggested the clinical trial as an alternative to the CBD legalization. The committee rejected that idea, but Figueroa and others in the Otter administration worked throughout March to achieve the Office of Drug Policy's first-choice outcome of replacing the bill with a clinical trial of the drug Epidiolex, which is derived from CBD oil and manufactured by GW Pharmaceuticals, a British company.

Emails reveal that Figueroa was laying the groundwork for just such a clinical trial by March 8, when she received a "preliminary cost analysis" from Robert Wechsler, a Boise-based physician who specializes in treating epilepsy and also serves as president of the Epilepsy Foundation of Idaho.

Wechsler served as a de facto consultant to the Otter administration during the CBD oil debates, and in emails obtained by Reason through an open records request, Wechsler consistently expressed skepticism about CBD's effectiveness and warned against legalization.

In one message to several of Otter's top advisers, he argued that parents' perception of CBD oil was clouded by the "emotional nature" of the issue. "My fear is that, if CBD is made widely available in an uncontrolled way, families will run to it because of the hype," he wrote.

At the same time that Wechsler was offering candid advice to the administration and angling for a state contract, he was also maintaining a professional relationship with Hunter Land, a medical science liaison for GW Pharmaceuticals.

Two weeks after Otter's veto, Wechsler forwarded an email from Land to Figueroa, which Figueroa forwarded along to Perkins and other top Otter staffers with the comment that the information from GW Pharmaceuticals "will be important when discussing any future legislation regarding CBD oil."

In that same email chain, Wechsler offered "cudos [sic] to the governor for not letting [the CBD oil bill] squeak by."

In June 2015, the state signed a $223,000 contract with Wechsler to run the Epidiolex trial. Wechsler did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

A spokesman for GW Pharmaceuticals told Reason the company did not attempt to influence the decision-making process in Otter's administration.

"We operate outside of that scenario," said Stephen Schultz, a spokesman for GW. "All the work we do in the United States is authorized by the FDA and the DEA and as far as the local level and state level, what happens there doesn't effect our program."

The Limitations of A Clinical Trial

Substituting the CBD oil bill with the limited clinical trial of Epidiolex was an ineffective way to alleviate the suffering of people like Josh Phillips.

In internal documents and statements to the media, the Otter administration stressed that a clinical study was better for children in Idaho suffering from epileptic seizures. Administering a drug like Epidiolex instead of letting families seek out CBD oil from marijuana growers in other states would ensure that patients were getting consistent, purified products and were being treated under the oversight of a neurologist, Figueroa wrote to lawmakers while the bill was still advancing through the legislature.

The reality of the study, however, was much more limited. Only 25 children were allowed to enter the state's clinical trial. Anyone who didn't qualify or wasn't selected was left with nothing. No Epidiolex. No CBD oil.

That includes Josh, who turned 18 two months before the cut-off date for the trial, which was only open to minors.

In other cases, the limits of the clinical trial forced some parents to make heart-wrenching decisions.

Sara and Ron Gambassi have twin 13-year-old girls, Clare and Julia, who suffer from epileptic seizures brought on by CFC, a rare physical and cognitive developmental disorder. With a limited number of slots in the trial, Sara and Ron made the difficult decision to only put one of their kids, Clare, into the program.

The Gambassis told Boise State Public Radio (BSPR) in February that, had the bill been signed, they would have sought to treat both daughters with CBD oil from growers in Colorado.

"We're reminded every day when [Julia] has seizures of that decision, that it was vetoed," Sara told BSPR. "It's not just we heard the news and it was over. We see her every day having seizures. We see her having seizures and hitting her head, and because she's non-verbal she can't even tell us how it feels."

The trials of Epidiolex might eventually produce a drug that successfully treats seizures, and that drug might eventually find favor with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), allowing it to be prescribed by doctors across the country. According to the company's year-end report for 2015, GW Pharmaceuticals is treating approximately 350 children with the new medication at 32 clinical sites in the United States (Schultz, GW's spokesman, says more than 1,500 people have recieved Epidiolex, including those in FDA clinical trials and those in state-level programs), and GW hopes to use the results of those trials to obtain federal approval, which it needs to begin marketing Epidiolex in the United States. The company plans to file for FDA approval in 2017.

So far, the company is reporting "promising signals of efficacy," with a median reduction in total seizures of 45 percent across all patients who have been receiving the drug for at least 12 weeks. About half the patients in the clinical trials have seen a better than 50 percent reduction in seizures, GW reported at the end of 2015.

But even if the drug does win approval from the FDA at some later date (in one email, Figueroa says approval could come in 2017), does it make sense to prevent children suffering intractable seizures from getting CBD oil in the meantime and as an alternative?

"We don't know that [CBD oil] will work, but we believe that it will," said Hollie Bunderson, whose son, Scout, has been suffering epileptic seizures since he was a few months old. Now 7, Scout has had four brain surgeries and has been given a wide variety of anti-seizure drugs, without success.

Bunderson would prefer to give her son CBD oil rather than a cannabis-derived drug like Epidiolex. "I believe God did it right in the first place, and we would like to be able to try the medicine that he gave us, the way he intended," she told the Senate State Affairs Committee during the hearing on the CBD oil bill.

The state has continued to enforce the prohibition against CBD oil, forcefully.

In October 2016, Kelly Osbourne, a 23-year-old mother, was arrested and charged with child endangerment for giving her daughter, who suffers from seizures, marijuana-infused butter. The Idaho Department of Health and Welfare took Osbourne's two children away from her, according to local media reports.

"They've already taken my life—they've taken my kids—so at this point, I really don't have anything else to lose," Osborne told the Twin Falls Times-News.

What's Next?

The Otter administration says cannabis-derived drugs like Epidiolex are preferable to CBD oil because the drug is extracted using medical equipment and is rigorously tested to ensure that it's consistent and free from contaminants. They contrast that with "artisanal CBD oil" that has not been approved by the FDA and could come in a wide range of potencies, depending on who is making and selling it.

"Using artisanal CBD oils can cause risk in patients because the products are unregulated," warns the Office of Drug Policy, which maintains that medications should be approved through the FDA testing process rather than by legislation.

It's true that FDA approval of CBD oil drugs would make it easier for millions of patients to access those drugs. But the agency has not yet approved Epidiolex or any other CBD oil derivative, and there's no timetable for when it might do so. That means people like Josh Phillips, Scout Bunderson, and Julia Gambassi have no choice but to wait. And Butch Otter, the man who once fought the EPA over his backyard pond and challenged the federal government's decision to link highway funds to the legal drinking age, is now saying the FDA should be the sole arbiter of what medical treatments Idahoans can access.

"The governor made a mistake" by vetoing the bill, says Rice. "I can understand the governor trusting the state police and the prosecutors. I don't blame him, but I do disagree with him."

The state legislature could give Otter the chance to fix that mistake when it convenes for a new session on January 9.

"We need to ask whether the prohibition against marijuana is worth the cost."

The Idaho Freedom Foundation, a free market think tank in Boise, is making the CBD oil (and, more broadly, the issue of marijuana reform) a centerpiece of its efforts for the new session. The organization has produced a documentary about Josh Phillips and his battle with the state government. It is currently playing in theaters around the state and available on the organization's website.

"We need to ask whether the prohibition against marijuana is worth the cost," says Wayne Hoffman, president of the group. "The main issue has to do with Idahoans making their own medical choices, and those choices being criminalized."

Rice says he would still support a CBD oil bill, but sees other things as being higher priorities at the moment. Working on a bill that the governor would probably just reject again is not worth it.

The threat of another veto hangs over any discussion of the topic in Boise and makes it less likely that lawmakers will spend their limited time in session (Idaho's legislature meets for less than three months each year, from early January to late March) on CBD.

"The governor's position remains the same," says Hanian, Otter's spokesman. "He will weigh each bill on its own merits. As is his custom, he does not discuss legislation expected to come up during the upcoming session, until and unless it reaches his desk. There are some exceptions to that rule, but this is not one of them."

Meanwhile, the Phillips family feels betrayed by their governor. "He needs to go spend a week with a family that has a child that has epilepsy, and then he would understand how hard and how scary it is," Jeanette said. "It should be our decision. Josh is our son. He's not the state's. He's not Butch Otter's. He's ours."

Otter's veto grew out of a system controlled by powerful interests who benefit from the maintenance of the status quo. Law enforcement wants to keep fighting the war on drugs—even when that means fighting kids with seizures—because it provides an endless stream of reasons for police departments to be given more money and the latest tech, with few questions asked. And pharmaceutical companies worry that legal weed will undercut the market they've spent decades capturing, because it provides an alternative for people suffering from pain, seizures, and other ailments. None of those incentives are changing, even as the edifice of marijuana prohibition crumbles away in other states.

Josh Phillips was too old to get into the Epidiolex study. At 18, he is no longer a child, although the state continues treating him like one by preventing him from making decisions for himself about how to treat his medical condition.

Josh says he's now using CBD oil in violation of state law, though he understandably does not want to discuss how he is obtaining it. He believes it is helping him. He reports having fewer seizures, and less severe ones. He's been able to maintain a part-time job and he's helping coach the high school wrestling team, helping others chase the state title that eluded him. He hopes to drive a car one day.

Other Idaho families with seizure-stricken children have moved to Colorado or Utah or Washington to get the treatment that is legal there but illegal at home. Every state that borders Idaho has legal marijuana or legal CBD oil.

The Phillipses say they are staying put in Salmon. It's the government, they say, that must change.

"I like to win, not lose," Josh says, showing the spirit that made him a standout wrestler. "I'll fight until I win."

Show Comments (43)