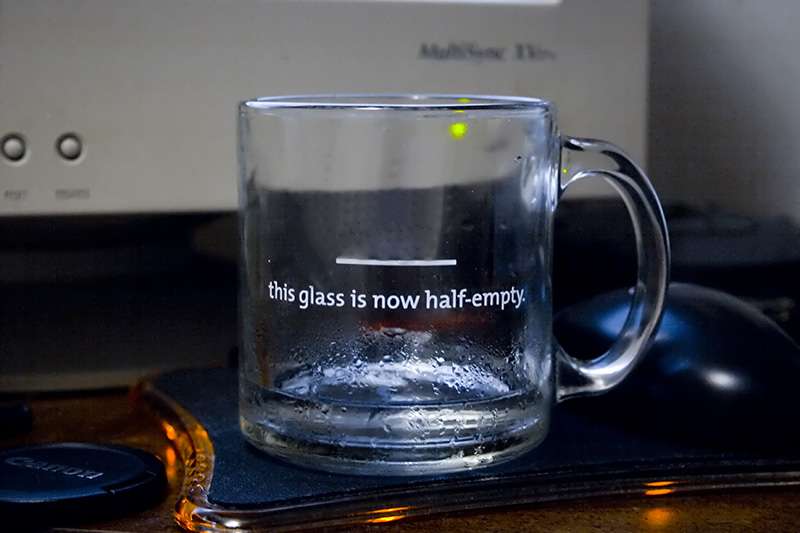

Optimism or Pessimism? Let's Try Realism

The point isn't to see the world though rose-colored glasses or through a dirty windshield, but to see the world as it actually is.

Two Washington journalists I have long admired, George Will and Jeffrey Goldberg, had columns last week on the question of optimism and pessimism. They took more or less opposite sides, leaving this non-Washington-based columnist an opportunity to try to arrive at my own position on the question.

Will wrote, paradoxically, "Looking on the bright side, perhaps this election can teach conservatives to look on the dark side. They need a talent for pessimism, recognizing the signs that whatever remains of American exceptionalism does not immunize this nation from decay, to which all regimes are susceptible."

He went on, "Pessimism need not breed fatalism or passivity. It can define an agenda of regeneration, but only by being clear-eyed about the extent of degeneration."

Goldberg, in a piece for The Atlantic prompted by the death of Israeli politician Shimon Peres, mourned the loss of Israel's "chief optimist." Goldberg criticized Israel's current prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, writing, "he must shed himself of at least some of his paralyzing pessimism."

Goldberg concluded his column: "As Peres famously said, optimists and pessimists die the same way. They just live differently. Despite it all, Peres chose to live as an optimist. It is not too late for Netanyahu to do the same."

So Will is counseling American conservatives to be more pessimistic, while Goldberg is counseling Israel's premier—a person who is arguably the most successful and significant conservative politician in the world since Reagan and Thatcher left office—to be less pessimistic.

Which one is right?

My own view is that to some degree the optimism versus pessimism discussion is a false dichotomy. The point isn't to see the world though rose-colored glasses or through a dirty windshield, but to see the world as it actually is.

Some situations merit cheerfulness; others merit gloominess. Unwarranted cheerfulness is a mistake; so is unwarranted gloominess.

In the Israeli case, Shimon Peres, heroic though he was for developing Israel's nuclear deterrent and rescuing Ethiopian Jewry, was nonetheless, in retrospect, probably unduly optimistic about the prospect of peace between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization. And Netanyahu's pessimism about the prospect of such a peace is nonetheless rooted in a certain optimism that Israel itself will endure and flourish despite international ostracism and ongoing violent attacks.

In the American case, Will apparently holds out hope that if only Americans realize precisely how badly we are going down the tubes, we might be able to save ourselves. This itself is a kind of combination of optimism and pessimism, almost like the friend of an alcoholic or drug addict hoping that the addict will "bottom out" in such a miserable stupor that the despair of the moment is the first step on the road to recovery.

If I have a dispositional tilt in these matters overall it is toward optimism; how can one not in a world of technological progress—smartphones, jet travel, the Internet—and a past century that saw the defeat of both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union? Well, easy enough: the jet travel enabled the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the smartphones and internet enable ISIS beheading videos, and anyone who views the defeat of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union as evidence for optimism ignores the fact of their rise and the tens of millions that they murdered, which are evidence for pessimism.

The wisest thing I have ever read on this general topic comes from the Jewish sage Saadia Gaon (882-942), whose The Book of Beliefs and Opinions includes this passage: "For all well-being in this mundane world is bound up with misfortune, and all happiness with hardship and all pleasure with pain, and all joy with sorrow."

That insight suggests what we need in the world is not more optimists or more pessimists but more people whose eyes are open to seeing the world as it really is and whose minds are open nonetheless to imagining how it might be improved.