The Man Who Turned Beauty into an Actual Cult

Documentary takes viewers inside the place called Buddhafield.

Holy Hell. CNN. Thursday, September 1, 9 p.m.

One man's cult is another man's religion. I remember listening with amusement some years back to an argument between a member of Rev. Moon's Unification Church and a rather strident Christian critic who was fulminating on the obvious absurdity of the reverend's (ambiguous) claim to be the messiah. Why would God, the man snapped, choose a peasant from a remote Korean mountainside village as his messenger? Replied the Moon follower, wide-eyed: "You mean, instead of an illiterate Palestinian carpenter?"

So I'm always dubious about the loose use of the word "cults," and even more so about their supposed dangers. As a second-generation atheist, it's not so obvious to me why, say, Rev. Moon's communal group homes are any more sinister than cloistered Catholic monasteries.

I say all that so you'll know that when I tell you that Holy Hell, a documentary about a creepily eccentric spiritual community led by an extra from Rosemary's Baby, is aberrantly fascinating and more than a bit unsettling, I'm not just weirded out by the unfamiliar rituals of an off-brand religion. Buddhafield, as the group is called, has left a trail of disillusioned followers with broken hearts and busted bank accounts in its churning wake.

One of them is Will Allen, the writer and director of Holy Hell, which has been kicking around the festival circuit this year and gets its first mass exposure next week on CNN. Allen spent 22 years as Buddhafield's house videographer and propagandist before breaking away in 2007, taking with him countless hours of revealing footage.

Allen, a recent film-school grad trying to break into the movie business, was introduced to Buddhafield by a sister who bumped into some of the followers in West Hollywood in the mid-80s. They didn't have any of the standard cult accoutrements—no shaved heads or flowing robes or saffron incense. In fact, they were mostly socially conventional and startlingly attractive (that, it would turn out, was not by chance) and formed a lively, funny crowd. "Constantly, your soul was being fed with love and inspiration and awe," wistfully recalls another new recruit of the day.

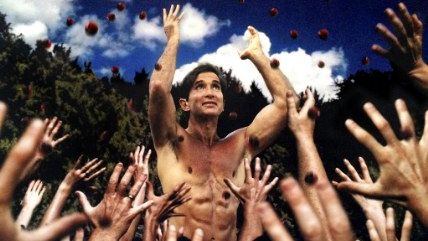

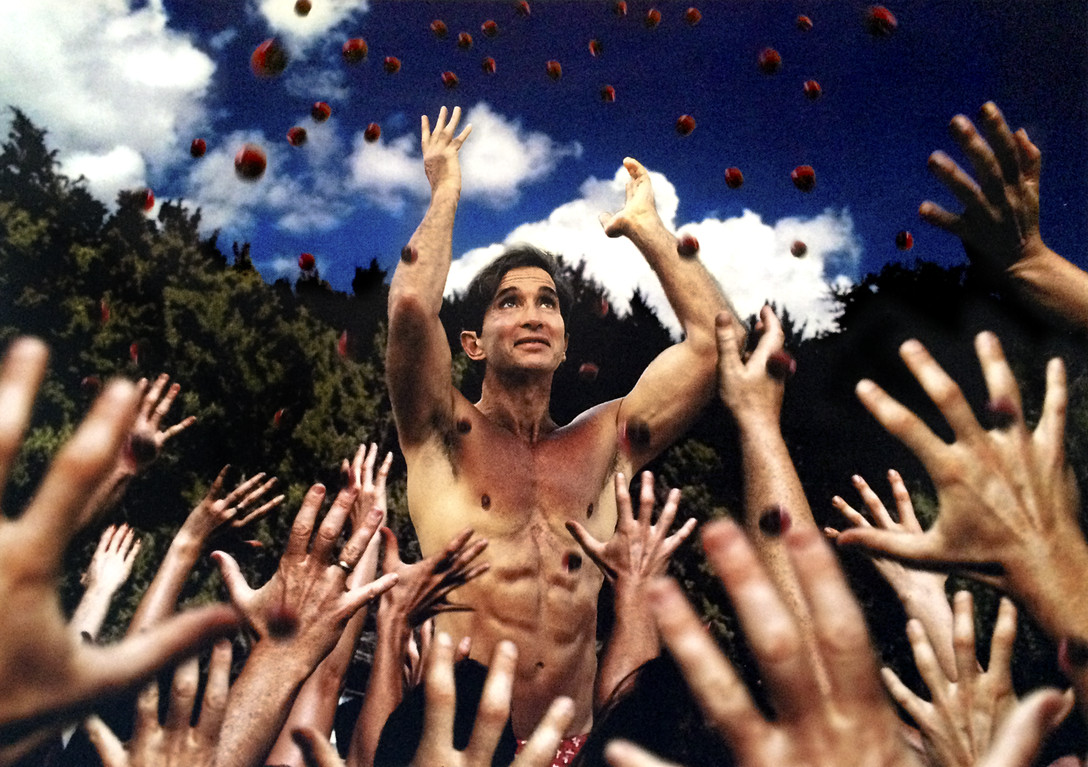

Buddhafield's leader was an elfin former ballet dancer and bit-role actor—you can see him in the crowd at that Satanist party at the end of Rosemary's Baby—who called himself Michel. Frequently clad in little more than a Speedo, striking dramatic poses and leveling smoky gazes apparently stolen from old Valentino movies while he spoke in an intriguing accent of indeterminate national origin, he preached a blend of Buddhism, Hinduism, and New Age mysticism that the West Hollywood crowd found irresistible. ("His energy was still, and I thought, 'What a beautiful man,'" explains one follower in the fractured argot of the spiritually overdosed.)

Pretty soon they'd all moved into a communal setting from which radio, TV, and sex were banned. (And especially the wages of sex; pregnant women either had to undergo abortions or leave the group.) Compulsory hypnotherapy, in which the Buddhafielders had to disclose their most intimate secrets, took place once a week, at $50 a pop.

"Service" was required, too, especially to Michel, who needed drivers, helpers and, after a while, somebody to carry his throne, literally. What service was directed outside the group itself was often hilariously misconceived. One acolyte who hadn't yet moved in with the group recounts spending hours creating artistic fruit salad renditions of scenes like The Last Supper for his roommate, only to discover the guy was simply shoveling them into a blender for smoothies without so much as a glance.

The most assiduous of Michel's devotees were invited to undergo The Knowing, which was described as "God revealed to you in its purest form." Which, the elite few who experienced it told their envious colleagues, involved a lot of changing shapes and colors, as if God were the toner running the light show at the Fillmore West. He also sounded like a mean SOB. When Michel offered Allen a chance at The Knowing, he suggested snapping up the offer because "he had been up all night, fighting with God, fighting for my life." God, it seemed, had Allen penciled in for a fatal accident instead of an epiphany.

Allen, impressed, went ahead. And this is the only point at which Holy Hell seems to blink. "There was no denying the beauty I was experiencing," Allen recounts cryptically. "But I was overwhelmed that too much was being asked of me, and I was getting in too deep." What exactly that means is left unsaid, though perhaps there's a clue later in the film.

When angry parents began pressing for an investigation of Buddhafield (members had been ordered to "detach" from their families), Michel went underground, then surfaced again to summon his followers to Austin. There the reconstituted group got weirder and weirder, building—and tearing down, and rebuilding, several times, at Michel's whim—a huge theater for opulently staged ballets that were rehearsed for a year at a stretch, then performed just once, and only seen by the Buddhafielders themselves.

Meanwhile, as Michel staged a new recruitment drive, it became apparent that the reason so many members looked like Hollywood starlets was that they were chosen, in large part, for their looks. Those who fell short of the mark were encouraged to get plastic surgery—and it was soon obvious that Michel was using them to test-drive the procedures before undergoing them himself.

It was in Austin that the group's facade cracked in the face of emails circulated by dissidents. Their most damaging disclosure was that the Buddhafield ban on sex didn't apply to Michel himself, who was sleeping with several of the male members, none of whom knew about the others. The revelation was shattering far beyond Michel's obvious hypocrisy: Several of his paramours were not gay and consented to sex with him only because they thought it signified a special relationship with their leader.

"I resisted, and I didn't want to be with him, and I would cry sometimes," says one of the men in Holy Hell, recalling an oft-repeated conversation in which Michel would counter his objections, "It's about your childhood, who are you resisting?" The man's reply—"I'm resisting you, I don't want to have sex with you"—would simply be parried once again, "No, no, let's go back to your childhood… ."

"He was masterful at getting what he wanted," the follower says. "And somehow after this process I would be bowing at his feet, saying, 'Oh my God, thank you, how do you always bring me back to this beautiful place?' And I'd get fucked again."

Accounts like this one abound in the latter part of Holy Hell as it describes Buddhafield's implosion in the face of the sexual disclosures. (Including one from Allen, who also admits to sleeping with Michel, perhaps what he was referring to as the high price of The Knowing.) Other flim-flammeries ran the gamut from fake medical miracles to brutal financial exploitation. One woman remembers leaving the group after two decades with just $45 to her name and the feeling that "I was dropping through this trap door, it was black and there was no bottom."

The word "abuse" is freely used. And even even the most hard-headed (or, if you prefer, -hearted) rationalist is likely to feel some sympathy for these shattered people, and some resentment toward a man who exploited their devotion.

But breaking somebody's heart is not the same thing as breaking his bones, at least not legally. If cajoling reluctant sexual partners with false pledges of exclusivity were a violation of the law, every singles bar in North America would have a police padlock on the front door.

All the members of Buddhafield were adults, and they were mostly well-educated. They were never held against their will—quite the opposite. Anybody who didn't accept Michel's quirky and demanding doctrines was asked to leave. The truly alarming question at the dark heart of Holy Hell is why, for so many of his flock, remaining with an obviously vainglorious and exploitative charlatan was preferable to the unthinkable alternative of leaving. Why does charisma so often trump common sense? It's a question that echoes well beyond the territory of saffron incense and shaven heads, or even smoky stares and Speedo struts.