Obama's Faint Praise of Hillary is Either Machiavellian or Dumb

The president characterizes his former secretary of state's use of a private email server as "careless," but under the law it's negligence.

President Barack Obama's recent remarks to

my Fox News colleague Chris Wallace about Hillary Clinton's email issues were either Machiavellian or dumb. It is difficult to tell from them whether he wants the mountain of evidence of her criminal behavior presented to a federal grand jury or whether he wants her to succeed him in the White House.

He cannot have both.

His efforts to minimize his former secretary of state's diversion of emails from government-secured servers to her own non-secure home server by calling it "careless" may actually harm her in the eyes of the public or even serve as a dog whistle to the FBI. That's because carelessness is a species of negligence, and espionage, which is the failure to safeguard state secrets by removing them from their proper place of custody, is the rare federal crime that can be proved by negligence — to be precise, gross negligence.

Gross negligence is the failure to perform a high legal duty with the great probability of an improper result — for example, driving a car 90 miles per hour in New York's Times Square. The high legal duty Clinton had was to safeguard state secrets; the improper result is the exposure of those secrets contained in her emails.

What did she do that was criminal, and who was harmed by her behavior?

Clinton knowingly diverted all of her governmental emails from secure government servers to her own non-secure server in her New York residence. Among the 60,000 emails she diverted were 2,200 that contained state secrets. Because the essence of espionage is the removal of secrets to non-secure venues, the crime is complete upon removal. So Obama's statement in the Wallace interview that Clinton caused no harm is irrelevant. In espionage cases, the government need not prove that the defendant caused any harm.

Obama's further effort in the Wallace interview to minimize the classification of secrets into the statutory categories of "confidential," "secret" and "top secret" by snarkily commenting that "there's classified and then there's classified" is not what one would expect from someone who has sworn to take care that all federal laws are enforced.

Obama has interpreted that duty so as to permit his Department of Justice to prosecute for espionage both a sailor when he took a selfie inside a nuclear submarine and sent it to his girlfriend and a Marine lieutenant who correctly warned his superiors about an al-Qaida operative masquerading as an Afghan cop in an American encampment but mistakenly used his Gmail account to send the emergency warning.

The evidence of Clinton's failure to safeguard state secrets is overwhelming because of the regularity of its occurrence. The evidence is well-grounded, as some of the secrets were too grave for the FBI to review and all came from her own server. And the evidence is sufficient to indict and to convict because it was obtained legally and shows a four-year pattern of regular, consistent, systematic violation of the laws requiring safeguarding.

Obama's suggestion that some secrets were not really secret is also irrelevant, because Clinton, like the president, swore to recognize secrets and to keep them secret, no matter her opinion of them.

The FBI knows this and is taking it far more seriously than the president or Clinton.

Just last week, the team investigating Clinton sought and received the extradition to the U.S. of a man who was imprisoned in Romania for computer hacking. One of those he hacked is Clinton's confidant Sid Blumenthal, to whom she sent many emails containing state secrets. What will the hacker tell the feds he saw?

Clinton's surrogates began taking her legal plight seriously in the past few weeks by arguing that her behavior was no different from that of other former high-ranking executive branch officials who occasionally and accidentally took top-secret documents home or discussed top-secret information in non-secure emails and that the consequences for them were tepid or nonexistent.

Yet there is no comparison between these occasional lapses and the planned and paid-for four-year diversion of secrets that Clinton orchestrated. Moreover, there is no instance of unprosecuted behavior that her supporters can cite that involves the sheer volume and regularity of the failure to safeguard that we see here.

Though the government need not prove intent, there is substantial evidence of Clinton's intent to commit espionage from three sources. One is Clinton's email instructing an aide to remove the "secret" designation from a document and send it to her from one non-secure fax machine to another. The second is the Blumenthal hacking incidents, which occurred during her tenure as secretary of state and which did not stop her from emailing him from her home server. The third is a federal rule that permits the inference of intent from a pattern of bad behavior, of which there is ample evidence in this case.

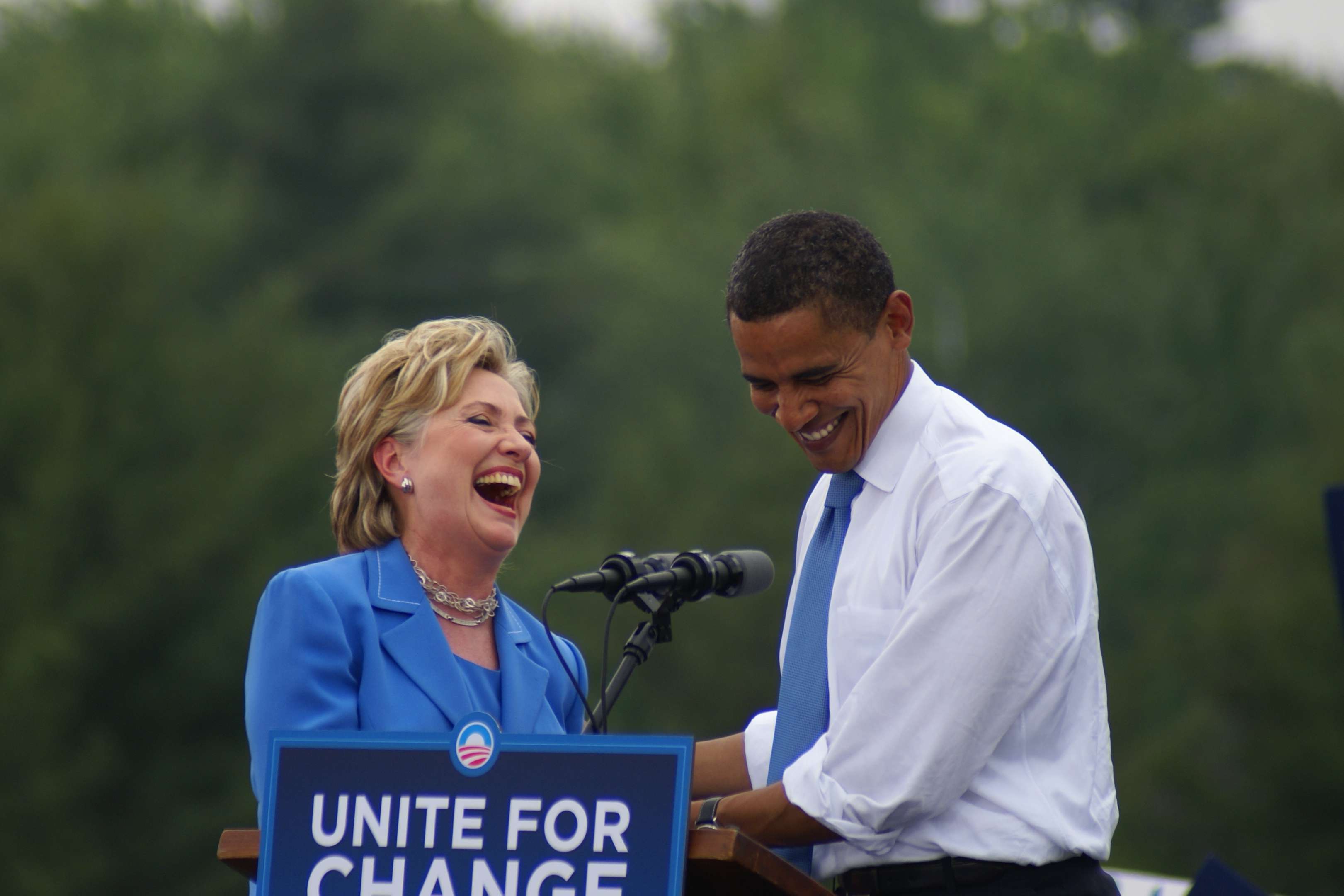

On the same weekend that the president was damning Clinton with faint praise and cynically offering what he must have known were irrelevant legal defenses, Clinton continued her pattern of persistent public laughing about and dismissing the significance of the FBI investigation of her.

That attitude — which is recorded and documented by the FBI — must have caused many of those investigating her to conclude that she understands the predicament she is in but is minimizing it. Or she may be a congenital liar who is lying to herself. Either way, they await with eager anticipation their interrogation of her, should she foolishly submit to one.

COPYRIGHT 2016 ANDREW P. NAPOLITANO | DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM

Show Comments (63)