What the Heck Is the First Amendment Defense Act, and Should We Be Worried?

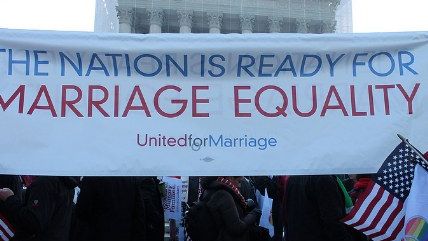

How far does law preventing federal retaliation against opponents of same-sex marriage go?

When "religious freedom" gets invoked in the United States, it can be a mixed bag. It can be a term legitimately be used to describe the right of Americans to express their faith how they choose and associate accordingly, provided they don't violate the rights of others. Or it could be invoked inappropriately as a justification for government discrimination, as was the case of Kim Davis, the county clerk in Kentucky who tried to use her religion as a reason not to comply with the Supreme Court's Obergefell decision that made same-sex marriage recognition the law of the land.

During the Supreme Court's hearing for Obergefell, justices debated whether a decision to mandate federal marriage recognition could lead down the line to punishment or withholding of funds for religious schools who receive federal money if they continue to decline to recognize same-sex marriage. After all, religion used to be the justification for rules against interracial marriage, and Bob Jones University was ultimately told that it could not keep its tax-exempt status if it had rules against interracial marriage or dating. Tellingly, those arguing in favor of same-sex marriage recognition couldn't say for sure that this couldn't happen again for colleges that won't, for example, admit married gay couples.

When the Obergefell ruling upheld gay marriage recognition, the concern that religious colleges would not be able to maintain their objections became a significant concern for religious conservatives. Earlier in the year, Rep. Raul Labrador (R-Idaho) and Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) introduced the First Amendment Defense Act (FADA). The stated intent of the law was to prevent the federal government from punishing or engaging in discrimination against people in certain ways because they believe that marriage should be between a man and a woman only or that sex should be confined to marriage.

The list of areas the laws is intended to apply seems limited at first glance. It would prohibit the government from revoking tax exemptions or refusing to allow tax deductions for charitable donations by or to these groups or individuals. It would prohibit the federal government (only the federal government) from denying grants, contracts or loans, or employment to people because of their positions on same-sex marriage. It would also prohibit the government from denying benefits to people for holding such positions, and it would require the government to accept the accreditation or licensing of those who believe or act according to their positions.

While that seems like a limited list, there was also a final sentence saying the federal government may not "otherwise discriminate against such person." That's awfully vague and could mean any number of things, including federal employees using their religious beliefs to not do their jobs. What started off as a bill to keep the federal government from denying tax exemptions to religious schools ended up possibly creating a phalanx of federal Kim Davises. As such, Reason contributor and Cato Institute Fellow Walter Olson warned against FADA because of its vagueness in a piece for Newsweek:

So for openers, FADA doesn't try to distinguish rights from frills and privileges: So far as I can tell, someone who is denied an ambassadorship or an invitation to a White House dinner because of disliked political views is covered, just like someone fired from his or her job. And "his or her" isn't quite right either: The bill covers artificial legal persons both profit-making and nonprofit, while also defining "federal government" to include all three branches and every element thereof.

The sum of this would be to create an extremely broad new category of anti-discrimination law—retaliatory discrimination based on a certain set of beliefs or acts—which would offer protected group status to powerful institutions as well as individuals, and afford very valuable legal leverage: recipients of federal subsidies, for example, could challenge any cutoff as motivated at least "partially" by political animus.

Astoundingly, the protection would run in one direction only: It would cover those who favor traditional definitions of marriage, while leaving those who might see merit in same-sex marriage or cohabitation or non-marital sex perfectly exposed to being fired, audited or cut off from public funds in retaliatory ways.

The good news is that Sen. Lee absorbed this criticism and prepared changes to the legislation. His new draft (read here) eliminates the part that says "otherwise discriminate against such a person," making it more specifically about the federal government attempting to punish people or organizations for their marriage views by denying them federal contracts or tax exemptions. It no longer appears to give coverage to federal employees refusing to do their jobs by, for example, refusing to process tax forms from married gay couples. It's still a one-way street, though, as Olson warns. Guess the First Amendment right to support same-sex marriage recognition doesn't need defending?

The bad news, for Lee anyway, is that his updated version of FADA is not the one that shows up on Congress' website or when somebody searches for the legislation on Google. It's still the broader version of the law with the potential for abuse. I did check with Lee's office to make sure is the revised version is the one they want passed. It is.

This matters now because conservative organizations the American Principles Project, Heritage Action for America, and the Family Research Council are pushing FADA in front of Republican presidential candidates and asking them to pledge to sign it into law during their first 100 days. Six candidates—Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, Ben Carson, Carly Fiorina, Rick Santorum, and Mike Huckabee—have signed the pledge. Jeb Bush, Rand Paul, and Donald Trump did not sign the pledge but have expressed public support for FADA.

But it's not clear which version of FADA we're talking about. The American Principles Project, which pushed for the pledge, links to the Heritage Foundation's analysis of the law, not to the law itself. So, when these conservative groups announced just recently who had signed the pledge, criticism went back to the earliest analysis of FADA, warning it would prohibit the federal government from disciplining federal employees who pulled Kim Davis-type refusals over same-sex marriage filings.

Furthermore, pushing the pledge for the American Principles Project is Maggie Gallagher of the National Organization for Marriage, the woman who, in the eyes of many in the gay community, is the face of national activism to prevent same-sex marriage recognition. Even if FADA does absolutely nothing that threatens federal recognition of same-sex couples, it's going to be tough trying to sell it to non-conservatives with her name attached.

In recent related news: A Massachussetts court ruled a Catholic school couldn't refuse to hire a married gay man for a non-administrative, non-educational position, despite the church's position on same-sex marriage.

Show Comments (210)