Mike Rowe to Bernie Sanders: Stop Telling Everyone College Is The Only Thing

Sanders implies "that a path to prison is the most likely alternative to a path to college. Pardon my acronym, but...WTF!?"

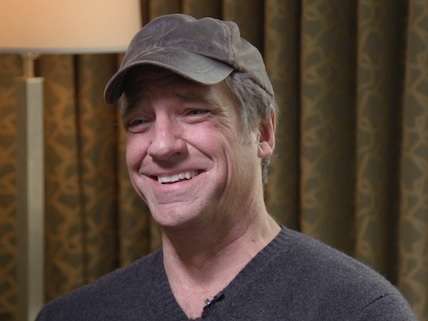

Mike Rowe, the popular host of CNN's Somebody's Gotta Do It and former host of Discovery Channel's Dirty Jobs, lays into Bernie Sanders for pushing everyone to go to college.

Rowe, whom Reason interviewed in December 2013 (see below), isn't against college, but he takes exception to the idea that the only legit way to get ahead these days is to get a university sheepskin. Rather, he argues, there are lots of excellent trade jobs available that many people would not only be successful at but happy to do. He sees a systematic, elitist attempt to denigrate such work in the name of college for all.

From Rowe's Facebook page:

Bernie Sanders tweets, "At the end of the day, providing a path to go to college is a helluva lot cheaper than putting people on a path to jail."

I wonder sometimes, if the best way to question the increasingly dangerous idea that a college education is the best path for the most people, is to stop fighting the sentiment directly, and simply shine a light on the knuckleheads who continue to perpetuate this nonsense. This latest tweet from Bernie Sanders is a prime example. In less than 140 characters, he's managed to imply that a path to prison is the most likely alternative to a path to college. Pardon my acronym, but…WTF!?…

It's a cautionary tale as predictable as it is false. But now, as people are slowly starting to understand the obscenity of 1.3 trillion dollars in student loans, along with the abundance of opportunity for those with the proper training, it seems the proponents of "college for all" need something even more frightening than the prospect of a career in the trades to frighten the next class into signing on the dotted line. According to Senator Sanders, that "something," is a path to jail.

I try not to be political on this page, because the truth is, arrogance and elitism are alive and well in every corner of every party—especially with respect to this topic. But I have to admit, this is the first time I've seen an elected official support the hyper-inflated cost of a diploma by juxtaposing it with the hyper-inflated cost of incarceration. Honestly, I'm not sure what to make of it.

When Reason TV interviewed Rowe, he made a similar argument. It's as forceful as it is convincing. Take a look or a listen. Transcript after the jump.

Diplomas vs. Dirty Jobs

TV host Mike Rowe on the educational bias against unglamorous, good-paying work

Nick Gillespie from the April 2014 issue

"If we are lending money that ostensibly we don't have to kids who have no hope of making it back in order to train them for jobs that clearly don't exist, I might suggest that we've gone around the bend a little bit," says TV personality Mike Rowe. Rowe is the longtime host of Discovery Channel'sDirty Jobs, where he takes on gigs straight out of Bob Dylan songs: working on fishing boats, sewer systems, oil derricks, slaughterhouses, and more.

"There is a real disconnect in the way that we educate vis-a-vis the opportunities that are available," he adds. "You have right now about 3 million jobs in transportation, commerce, and trades that can't be filled."

Rowe, who once sang for the Baltimore Opera and worked as an on-air pitchman for the shopping channel QVC, worries that traditional K-12 education demonizes good-paying, in-demand blue-collar fields while insisting instead that everyone get a college degree. Between the mikeroweWORKS Foundation and Profoundly Disconnected, a venture between Rowe and the heavy equipment manufacturer Caterpillar, the TV personality is hoping both to help people find new careers and to publicize what he calls "the diploma dilemma."

Rowe recently sat down with reason's Nick Gillespie to discuss the problem with taxpayer-supported college loans, the importance of a work ethic, the burden of regulatory compliance, and his own unusual work history. For video of the interview, go here or see the video embedded at the end of this article.

reason: We're doing everything we can to push every kid to go to a four-year college. What's wrong there?

Mike Rowe: It's not working. You've got a trillion dollars in debt on the student loan side. We have a skills gap.

reason: What do you mean by skills gap?

Rowe: You have right now about 3 million jobs in transportation, commerce, and trades that can't be filled.

reason: This is anything from carpentry to being an electrician, a plumber, construction-

Rowe: Heating, electric, truck drivers. Welders is a big one. There's a long list of jobs that parents typically don't sit down and say to their kids: "Look, if all goes well, this is what you're going to do."

reason: But these are actually jobs that are not only available but pay well.

Rowe: Yes, is the short answer. But of course, "pay well" is kind of relative. What they are mostly, in my opinion, are opportunities. A good welder right now can pretty much write his or her own ticket. Companies like Caterpillar, Bechtel, you can go down the list: They have had open shortages for decades. I talked to a kid the other day up in Butler, North Dakota. So it's Butler, right? It's cold. But he works on heavy equipment up there, makes over $100 an hour, works when he wants, paid for his house in cash, raising a family, no debt. People don't tell his story.

reason: Instead, we're telling everybody you've got to get that sheepskin, you've got to get the college B.A., otherwise you're not going to be happy or have any opportunity.

Rowe: It feels that way to me. That was my experience in high school, and I still hear the same platitudes today.

reason: You have a great story about your high school guidance counselor.

Rowe: Mr. Dunbar, yeah. He called me down, as millions of kids have been called down, to talk about my future. He was looking at some test scores and said, "You're not an idiot. You've got a shot at James Madison University in Maryland, maybe some other schools." I said, "I don't have any money, but more importantly, I don't have any idea what I want to do. So, while I figure that out, I thought I'd go to a community college." At which point he says, "Well, that's way below your potential," and pointed to the poster that said "Work Smart, Not Hard."

The thing about the poster wasn't just the bromide at the bottom. It was the image. On the left-hand side you've got a college graduate, recently matriculated, cap and gown, sun setting behind him, looking like he owns the world and the future. Next to him is a mechanic, holding a wrench, covered in grease or something worse, looking at the ground like he won the vocational consolation prize of all time. That was a very specific PR campaign for college, higher education.

reason: This was the late '70s?

Rowe: 1979, yeah. All PR campaigns always go too far, and they always, it seems, promote the thing they want to focus on at the expense of something else. Now, it's kind of egregious in education, but in my opinion, it shouldn't be shocking, because the best way to sell a truck is to talk about how lousy the competitor is. The best way to get elected is to talk about how creepy your opponent is. The best way to really promote college hard is to talk about how subordinate all the other opportunities are.

Now, as part of our ongoing campaign for the trades, we sell posters that say "Work Smart and Hard." I now play the role of the graduate standing there holding my degree looking somewhat confused by the industrial setting in which I find myself next to a far more aspirational tradesman. It's just another way to juxtapose these roles.

reason: What are the goals of the "Work Smart and Hard" campaign?

Rowe: We have to change the conversation and we have to challenge the existing protocol. The first thing is this general PR campaign around the trades. The second thing, there is a financial thing. The posters were only $10, but if I can get 20,000 or 30,000 of them hanging in guidance counselors' offices around the country, well that's fun. We take the money we raise, of course, and it goes into a foundation to keep the conversation going and to award what we call a work ethic scholarship.

reason: What is a work ethic scholarship?

Rowe: The scholarship business, as I understand it right now, rewards four basic things: intelligence, so you have academic scholarships; athleticism-if you can hit a three-pointer, we have money for you for days; talent, we reward talent; and of course need. Who's addressing work ethic? Who's affirmatively trying to reward the behavior we want to encourage? The behavior that mikeroweWORKS wants to at least talk about redounds to two things: the willingness to learn a useful skill and the willingness to work your ass off. Combined, we think that is something that ought to be affirmatively rewarded.

reason: When did the idea disappear that you should learn a skill that is actually useful or in need, and that you should work hard?

Rowe: That's a good question for a real social anthropologist. My own opinion is just that there's a kind of inertia that most parents would agree exists, and it's the desire to see something better for your kids than you had. The question is: What is better? Is it better right now today to have $140,000 in debt but a degree from Georgetown in law? Or is it better to be that kid I described up in Butler? I don't know. But there is an inertia that says the first one is a better thing.

reason: Let's talk a little bit about the college loan scam. You talk about how there's a trillion dollars in debt. Most of that principal will be paid off by the people who take the loans. But you're against the idea of taxpayer-supported loans for going to college.

Rowe: We hold the note. Whether I'm against it or not, I get a little curious about when it gets to a trillion dollars. If we are lending money that ostensibly we don't have to kids who have no hope of making it back in order to train them for jobs that clearly don't exist, I might suggest that we've gone around the bend a little bit.

reason: And pumping that extra money into the system allows colleges to raise their prices.

Rowe: Of course. The cost of a degree has increased so exponentially, I can't believe it's not daily news. Imagine any other commodity increasing at that rate.

I get it, education is hugely important. If there's one thing that's more important than education, it may be health and fitness, because what's the point if you're not functioning? But imagine if the conversation we have about colleges we have today applied to gyms. Imagine saying: OK, it's important to be healthy and fit, so what you need to do is spend $1,000 a month at the most expensive club in town, otherwise your heart might explode, you'll crap your pants, you'll get fat, nobody will love you.

reason: Obviously you've done some background research on this.

Rowe: I didn't want to say anything, but there's an odor.

reason: But you're not anti-college?

Rowe: Not at all. I'm not anti-gym membership. If you've got $1,000 a month and can go to the place with the shiny equipment and the cadre of personal trainers and the private Jacuzzi-do it and enjoy your protein shake in the privacy of your own largesse. Not your large ass, your largesse.

But if you can accomplish the same thing for $12 a month, I think it'd be prudent to at least put the two things on the table. And if I have to pay for part of your membership in either facility, I must get a little exercised about your ultimate choice if you can't pay it back.

reason: You come from a background in which your grandfather was a laborer. He worked with his hands, he built things. Did he say to you, "I want you to do things exactly as I did"? Or did he want you to have a job-you hear this all the time-where you don't have to wash your hands for 45 minutes when you come home before you eat dinner?

Rowe: He was fairly agnostic about my hopes and dreams. I wasn't. I very specifically wanted to follow in his footsteps. The guy could build a house without a blueprint. He only went to the eighth grade, but by the time he was in his thirties, he was a master electrician, carpenter, steamfitter, pipefitter.

reason: You've talked about how one of the best days you've ever had was when you first learned the pleasures of dirty work.

Rowe: I was maybe 10 or 11. We lived in a small little farmhouse with one toilet. I went down one morning, took care of business, stood up to flush it. For whatever reason I like to watch it go away, there's something satisfying about watching something that was just in me going away. On this particular morning, it went away and the toilet made a sound kind of like the pig noise in The Amityville Horror, a gurgling, demonic, sort of disappointing screech. Everything that had just been in me came flying backwards and covered me.

My grandfather lived next door. Obviously something between the septic tank and toilet had gone tragically wrong. My grandfather, being a magician of sorts, dug up the yard in just the right place, found the problem in a pipe, replaced the pipe. There was welding, laughing, cursing. My mother brought me my first thermos of coffee. My dad and my grandfather worked covered in crap for most of the day. I took the day off school to do it. It was a very satisfying day, because I was with the two most important men in my life, and I saw again, certainly not for the first or last time in my life, a real problem corrected. I wanted to do that.

The gene my grandfather had cruelly and horribly skipped right over me, and I washed out of every shop class there was in high school. It was my grandfather who ultimately said, "Look, you ought to think about getting a different toolbox."

reason: So he was like, "Sorry kid, you don't have the chops to become a master electrician, go into TV"?

Rowe: No, he didn't go that far. What he said was, "It doesn't matter what you do. You think you want to do what I can do. What you want to do is work in the way I'm working. So in other words, whether you're a TV interviewer or an opera singer or a writer, you can approach your craft like a tradesman."

And by that I mean like a freelancer, instead of, "OK, I need my job, and my job will be 30 years, and it'll come with benefits and it'll be provided blah blah blah." That's not working anymore. I was never really enamored of it. I like the idea of the classic freelancer. I always have.

reason: What are the ways you develop a stronger work ethic in people?

Rowe: I think it has to do with being suspicious of anything that's too easy, suspicious of anything that doesn't hurt a little bit. It has something to do with the willingness to find and take the reverse commute. That's the big lesson on Dirty Jobs.

There's another bromide, another platitude out there that always chapped my ass a bit, which is "follow your passion." My scoutmaster, my reverend, my dad, everybody growing up was like, "just follow your passion." It's terrible advice. On Dirty Jobs I met a lot of very passionate people, but very few followed their passion into their current vocation.

Les Swanson from Wisconsin cleaned septic tanks. I asked him one day-we were literally standing up to our nipples in the most indescribable bouillabaisse-"Les, what'd you do before this?" It's like 110 degrees, the sweat is running off his face, and he looks and me and he says-I swear-"I was a guidance counselor." He was a psychologist. I said, "Why'd you leave that?" And without missing a beat he said, "I got tired of dealing with other people's shit."

It was very funny, but it was also very instructive, because he always thought that what he wanted to do was the thing he was told he should do. He became passionate about something he really didn't care for. When it came time to make the change, he just looked around to see where everyone else was going, and just went the other way. It took him into a septic tank, his own business, a couple workers, very happy.

How do you know you're going in the right direction, how do you foster a good work ethic? I think you just have to identify the thing that most people don't want to do, figure out a way to do it, and figure out a way to love it.

reason: Should schools be more in the business of doing vocational-technical training stuff? Should it be businesses that are doing apprenticeships and building up interest and saying, "Look we can offer you a good job at a good wage with some honor and integrity"?

Rowe: I would if I had a big business. I don't know if they should do it. I don't want to should all over anybody, but I think that if I depended on a skilled workforce, I would not depend on the public education system to provide it for me. I would set up my own things internally and I would make sure I was doing things in the most effective way I could in terms of training the best candidate I could find.

But I do think that companies are at a kind of disadvantage, because so many kids who come to apply for the kind of work we're talking about, they have an expectation that's not realistic. They've been watching American Idol for too long. They just have an idea that I did my time in high school and maybe I even did my time in college, so where's my cheese? You want me to do what?

There's a real disconnect in the way we educate vis-Ã -vis the opportunities that are available. There's a disconnect between the companies that are providing the opportunities and the parents and guidance counselors who are advising their kids. Ultimately, the company is going to have to step in to provide the training that is required.

reason: You're a critic of credentialism. In a world where everyone graduates from high school-everyone graduates from college, it seems-how do we tell who's good and who's bad?

Rowe: I don't think we do. It's one of the reasons we fall in love with credentials. It's the same with falling in love with one-size-fits-all education. "Look, it's simple, all you have to do is go to college." "Look, it's simple, either you have your credentials or you don't."

I was at the Marine Corps ball a couple weeks ago. I go every year. I talk to them at it. You can't find work. Now eight months earlier, he's somewhere over there. He's got his service revolver in one hand, he's holding the femoral artery shut, he's saving a life, he's taking a life. The guy's qualified, but he's not credentialed. He can't get hired as a nurse.

All the c-words get tricky. Compliance-the hidden costs of compliance in the workplace today is staggering. The cost of hiring someone is not simply the cost of paying them their salary. On Dirty Jobs, I've talked to so many employers in every state, and after we shoot, usually over beer, we start to talk about the way things really are, what are the real problems. Compliance is always a word.

reason: That's compliance with a wide variety of state and federal regulatory agencies?

Rowe: There is an army of angry acronyms out there, and they each have a very specific agenda. And this is not a judgment call on OSHA or the EPA, or the SPCA or PEtA, but they all have their letters and they all have their marching orders and none of them are there to make your life easier. They're there to make you more compliant.

reason: I think one charge that can be leveled against you is that you're in the business of romanticizing blue-collar work. Hard physical labor, which wears people out, is hard. And I'm looking at a Bureau of Labor Statistics chart about earnings and unemployment rates by educational attainment. If you've got a high school degree, this is in 2012, your median weekly earning is $652. If you have a bachelor's degree, it's $1,056. If you've got a high school diploma, the unemployment rate is 8.3 percent. If you've got a bachelor's degree, it's 4.5 percent. What do you say to that?

Rowe: I suppose I'd get another graph with some other numbers and I'd say we're $1 trillion in debt. I get hundreds of letters a week from parents whose beautifully educated snowflakes are back home, sleeping on their sofa, but completely unqualified for any of the work that's available.

I'm not saying that what you ought to do is go to high school and then go straight to work. That view is just as ridiculous as saying to go into the most expensive school you can possibly get in and get your degree. Those two things are equally fallacious. There's got to be a component of a freelance mentality, a new understanding of basic margins. If you have 12 million people unemployed right now, most reasonable people would go, okay so we need 12 million more jobs. Except we don't. It doesn't work that way. If it did, we wouldn't have 3.9 million jobs available right now. It's an inconvenient truth to the prevailing narrative.

I'm not against job creation. I'm not against education. I'm not against any of those things. I'm just saying that the statistics I've seen, that are right in front of us right now, scream opportunity. The problem is, the opportunities they've been screaming for have been historically, consistently, and traditionally beaten out of our own aspirational wish-fulfillment.

reason: During his stimulus a couple of years ago, when President Obama talked about shovel-ready jobs, he also talked about how ATMs were taking people's jobs. It seems kind of odd-airplanes displaced railroads, but then you need mechanics to fix the airplanes, you need guys to fuel the airplanes, you need people walking up and down the aisle serving drinks on airplanes. Is technology the problem here?

Rowe: It's not a problem. The displacement theory is interesting. I first read about it in our industry, where the idea was the newspaper would displace the telegraph, movies would displace books, TV would displace movies, and on and on. It doesn't.

But the 8-track's gone. Sometimes things are displaced. Sometimes they're just re-imagined.

The first time I heard the phrase shovel-ready jobs, I was in a water tower in New York with the guys that replaced the wooden water towers on top of skyscrapers. A guy had a small TV, we were on break, everyone was watching it. Everyone just laughed at the expression and one of the guys I was working with said: He's going to have a lot more success selling shovel-ready jobs to a country that still values the notion of picking up a shovel.

reason: People growing up today, as opposed to maybe 30 years ago, recognize that companies like IBM, AT&T, and Sears are not long for the world-that the companies we assume will guarantee you lifetime employment are not around anymore. Part of your message is that recalibration.

Rowe: The welder is a really interesting example, because he's like the freelancer-he doesn't have a lance, he has a welding torch. And a good welder is a very artistic thing to watch. Many, many different kinds of welding exist, and the people who are good at it are almost savant-like. It used to be called the industrial arts.

All the press I read about the vanishing thing from high school was the arts. It really was voc-tech that went first and hardest. The idea that artistry can still exist with work is really important. When you separate work from artistry, you get the same problem you get when you separate clean from dirty or blue-collar from white-collar: You create a gap, and it's that gap to which all sorts of things fall, including expectations, including opportunity, including millions of jobs.

I look at welding as maybe the best example of everything we're talking about right now. The opportunities exist, the opportunities pay well and are wildly underserved, people don't aspire to it, and yet everything in this room requires it. Whether it's smooth roads or runways or cheap electricity or indoor plumbing or basic infrastructure: We used to look at the people that provided those services as vaguely heroic. Now it's not that we disparage them, we just don't look at them. And if we do, we just don't see them.

reason: Speaking of freelancing, or recalibrating, Dirty Jobs is over. Do you know what you're doing next?

Rowe: This is it. I'm going to do a series of interviews in hotel rooms around this great land talking about the changing face of the modern-day proletariat. The bad news is there will be no money.

reason: But the good news is there's room service.

Rowe: There's room service.

I'm living in the age of Honey Boo Boo. Not a bad thing necessarily-it's transitioning, just like anything else. We were joking before that the ducks have a dynasty and the Amish have a mafia and non-fiction television right now is being hugely impacted by writers. These shows have writers' rooms. Dirty Jobs is a very tough sell in that regard, because I didn't know how Dirty Jobs would end. I still don't, except that it's over, so I guess I knew it eventually would end. But episode by episode, segment by segment, what was really for sale on that show was uncertainty.

Viewers dug it. People liked the idea of no rehearsal, no scripts, no writers, no second take. That today makes people really anxious, and so we're seeing a much more careful, measured, controlled look at something that should be uncareful, unmeasured, and uncertain, in my opinion.

Rather than jump into some version of Dirty Jobs that is more controlled, I'd rather talk about some of the things I've learned from doing it and see maybe if there's a way to stay relevant in that space. Because really, I was lucky. I went to a community college, then I went to work, then I went back to school and I got my degree. But my real education took place in reality TV. Mostly in a sewer.

For more on Rowe at Reason, go here.

Show Comments (195)