Movie Review: In the Heart of the Sea

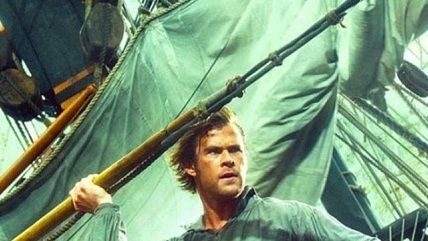

Chris Hemsworth in an old-school whaling tale.

Ron Howard's new movie is a high-seas adventure of a frankly old-fashioned sort. In the Heart of the Sea tells the story of the ill-fated Essex, a whaling ship out of Nantucket, which in 1820 was rammed and sunk by an enormous sperm whale some 2000 nautical miles off the coast of South America. This incident was the basis of Herman Melville's 1851 novel Moby-Dick, and Howard's picture is sprinkled with scenes showing the young Melville (Ben Whishaw) extracting the full, horrible tale of the Essex catastrophe, years after it occurred, from its last living survivor, Tom Nickerson (Brendan Gleeson). This is a useful framing device—it allows us to learn what became of the crew after their ship went down. But it's also a distraction: whenever we flash forward to Melville and Nickerson murmuring at one another ("We were headed for the edge of insanity!" the older man rasps), we keep wanting to get back to sea, to the listing ship and the terrified sailors. And of course the whale.

The story is built on an armature of class and commerce, set in the period when whale oil had transformed the world, lighting up its previously gloomy cities and making wealthy men of the ship owners whose vessels harvested this miraculous resource. The hero is tall, blond, chesty Owen Chase (Chris Hemsworth), a seasoned seaman who's expecting to be hired on as a captain for his next whaling expedition. But Owen is a farmer's son, and he's passed over in favor of a nautical newbie named Pollard (Benjamin Walker), the scion of a well-connected whaling family. Owen has to make do with being Pollard's first mate. Cue the classic shipboard clashes.

After some listless onshore business with Owen and his pregnant wife (Charlotte Riley), from whom he'll be parted for the next two years, he and the Essex finally set sail, and the picture gets down to business. The action is everything you'd want from this sort of movie. We see the athletic Hemsworth scrambling up into the rigging to free a jammed topsail. We see decks being swabbed and crew members muttering darkly after the clueless Pollard orders the Essex straight into a squall that nearly capsizes the ship. Then we hear someone actually hollering "Thar she blows!"

Whale pickings are generally slim, however. After a year at sea, with not much oil to show for it, the Essex puts in at an Ecuadoran port, where Pollard and Owen hear about a rich field of whales, and where it can be found. They also hear about a great white "demon whale," which they'll soon enough be meeting.

Howard shot the movie on the water (in the Canary Islands) and in a studio tank in England, and the great cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle does a fine job of putting us right into the midst of the action on the ship's lurching decks. But the digital effects are the real star of the film: the heaving, mountainous waves; the spectacular sinking of the Essex; the continuing attacks by the giant whale, apparently stalking the beleaguered sailors as they float off in their battered rowboats, guided by the tides to who knows where, or what. The scene in which the starving men contemplate the corpse of a just-deceased shipmate conveys the full extent of their desperation.

The movie has none of the metaphorical weight of Melville's book (or of the 1956 film that John Huston made of it—a picture sunk by the miscasting of mild Gregory Peck as the mad Captain Ahab). Hemsworth's physical brio and emotional reach center the movie (and Cillian Murphy's presence, as the ship's second mate, helps, too). But there's not much more to the movie than its rousing action. That could be fun for kids, but in a box-office season freighted with high-profile blockbusters, it might not be enough.

Show Comments (6)