Television Tackles Invasive Behavior—Both Digital and Romantic

CyberWar Threat and Crazy Ex-Girlfriend may make you paranoid for completely different reasons.

- Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. The CW. Monday, October 12, 8 p.m.

- Nova: CyberWar Threat. PBS. Wednesday, October 14, 9 p.m.

A couple of weeks ago on the ABC sitcom Black-ish, while the rest of the family was worrying about whether the household needed a gun for protection (and surprisingly, for a Hollywood production, the argument was not one-sided), nerdy teenager Junior warned everybody they were missing the real threat: "Cyberterrorism made burglary possible for fat guys who can't fit through windows."

Believe it or not, even that possibility is covered in CyberWar Threat, an engrossing new episode of the PBS science documentary series Nova that considers the problem of digital attacks from nearly every conceivable angle. About the only thing that doesn't come up is the propect of being stalked by a spurned sweetheart, but don't worry—The CW's got it covered with Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, a loopily entertaining comedy about courtship gone wildly off the rails.

Written by journalist James Bamford, who before Edward Snowden started spilling beans was almost the only person in America who knew anything about the National Security Agency (NSA), and veteran Nova producer Chris Schmidt, CyberWar is not only comprehensive yet gibberish-free, a rarity in tech journalism, but also realistic without being paranoid. (The irritating exception to the latter is the tease-in about a ruinous 2009 Siberian dam disaster in which the culprits, you learn after several minutes of breathlessly broody what-ifs, were not cyberterrorists but worn bolts.)

Like many Nova documentaries, CyberWar does a good job of explaining why seemingly abstract scientific and technological notions apply to everyday life. One of the show's most striking moments is a demonstration of computer malware known as Nuclear RAT (for "remote administration tool"), which allows somebody to not only watch what your computer is up to but record keystrokes, steal passwords and even switch on your web camera and watch you dancing along with old Wham! videos in your underwear.

Even on a strictly personal basis, that's alarming, with everything from pacemakers to home security systems to kitty-litter boxes now wired into computers that are in turn linked to the Internet. A University of Washington research team recently succeeded in hacking into a moving automobile's electrical and mechanical system, locking the brakes and sending the car into a skid toward a wall. And what is merely creepy when applied to your Hong Kong porn site becomes ominous when you think about its use against a computer that contains, say, nuclear launch codes.

The show's principal focus is a familiar one, the NSA. But unlike most recent journalism, CyberWar concentrates not on the NSA's domestic spying but its martial ambitions. Little notice has been taken, the documentary notes, that the agency has evolved "from a passive listener into an active spy, able to infiltrate, steal and if necessary attack in cyberspace."

Apparent case in point: Stuxnet, a computer worm unleashed in 2009 against centrifuges at an Iranian facility that produces enriched uranium, a key ingredient in both civilian nuclear-power plants and military weapons. The worm wreaked havoc that, depending on your perspective, was either spectacular or disastrous.

Officially the authors of the attack remain unknown, but the New York Times and other media—as well as NSA defector Edward Snowden, who was interviewed for CyberWar—have reported it was produced by the NSA in cooperation with Israeli intelligence.

Certainly it served their purposes. The worm was clearly designed to seek out and destroy the Iranian centrifuges; it spread through thumb drives rather than the customary vehicle, email, which allowed it to evade the deliberate lack of Internet connectivity in the facilities, and it targeted specific parts manufactured by the German company Siemens that the Iranians were known to use.

Once it penetrated the Iranian plants, the worm lay in wait for weeks before it began monkeying with the speeds of the centrifuges, aruptly speeding them up and then slowing them down until they went up in smoke. Hundreds were destroyed.

CyberWar's retelling of the Stuxnet case is in part a fascinating detective yarn, told in large part by the cybersecurity experts at Symantec, who were the first to dissect and study the worm after it began turning up on ordinary desktop computers in the Middle East. "It was immediately obvious to us, when we started studying the code, that this was not two kids in a basement in Kansas somewhere," says one.

But it's also a creation story in which the sound of something slouching toward Bethlehem echoes ominously in the background. Computer viruses are nothing new, but Stuxnet went beyond that to inflict physical damage, and in that sense CyberWar's fidgety references to the Siberian dam disaster have some resonance, even if only indirectly.

If Stuxnet was indeed the sound of a genie emerging from a bottle, the United States may well regret popping the cork. Stuxnet was swiftly followed by what to many experts looked like Iranian retaliation against computers of the Saudi Arabian oil industry and the U.S. banking industry.

As CyberWar notes, cyber attacks are sometimes called "the poor man's atomic bomb" because they don't require the vast resources of a wealthy nation-state, they can be launched utterly without warning ("no reports of troop movements to signal a threat, or air-raid sirens to give warnings," notes one expert) and their authorship can be cloaked in multiple layers of digital misdirection. President Obama slapped sanctions on North Korea after the massive 2014 hack of Sony, but nearly a year later, there's still no agreement among computer security experts about whether the attack even came from outside the company, much less Pyongyang.

No less than Michael Hayden, former head of both the NSA and the CIA, who resolutely approves of the destruction of Iranian nuclear facilities ("Crashing a thousand centrifuges in Iran? Almost an absolute good") admits on-camera that "this smells like August of 1945." He wasn't referring to chocolate Ovaltine or Betty Grable pinups.

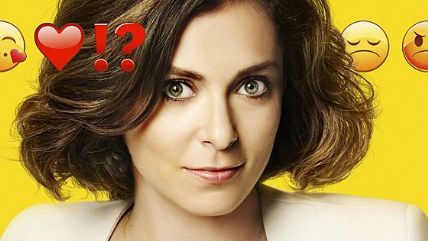

It's doubtful that even the NSA could come up with a countermeasure for the title character of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, whose compulsive stalking of a summer boyfriend of a decade earlier is out-weirded only by her propensity to burst into song while doing so, often to the accompaniment of a full marching band. Not since the short-lived, little-remembered and even-less-mourned Cop Rock tried mating the police-procedural to musicals has television been this barkingly mad.

Crazy Ex-Girlfriend stars Rachel Bloom as Rebecca, the newest junior partner at a ball-busting New York law firm, whose joyless career overachievement only serves to underline the throbbing mass of neuroses that direct her personal life.

One day on the street, she spots a summer-camp boyfriend who broke her heart at 16. (She: "You've awakened my sexual being for the first time. … this has been the best summer of my life." He: "You're like dramatic and weird. I think maybe we should take a break.") Groundlessly, she interprets his off-hand remark that he's moving to suburban West Covina, California ("two hours from the beach, four if there's traffic!"), as an invitation to join him.

She heads west, ditching Wall Street for a bargain-basement law firm where the entire office is in an uproar because somebody's emotional-support cat has just escaped. Amidst various musical salutes to such Southern California flora and fauna as shopping malls and giant pretzels, she makes an ally of her new bat-guano-bonkers paralegal (Broadway actress Donna Lynne Champlin), whose proposed strategy for conquest of the ex is, "Hit him like a bag of nails to the balls!"

Everything about Crazy Ex-Girlfriend is balls-out nutbaggery, including its origin: It started out as a half-hour comedy for premium-cable channel Showtime and somehow wound up on a network devoted mostly to high-school bitchery and boy-band vampires, where it's not always clear if the demographic target of 13 to 34 refers to age or IQ.

Bloom, the star, sometimes voices characters on the Cartoon Channel's Robot Chicken, but is best known for the viral video Fuck Me, Ray Bradbury (You write about earthlings going to Mars/And I write about blowin' you in my car). She appears a perfect match for executive producer Aline Brosh McKenna, author of such chick-madness parables as The Devil Wears Prada and 27 Dresses. Whether this lunacy can survive on The CW remains to be seen. If the show makes it to the big tap-dance production number without getting canceled, Bloom and McKenna can declare victory and go home.

Show Comments (9)