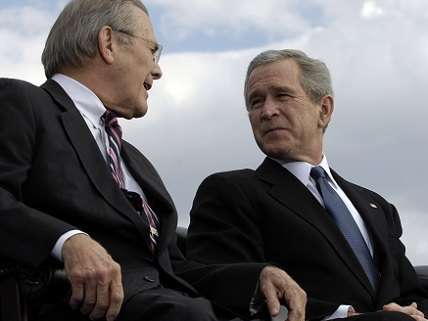

Donald Rumsfeld Says Goal of Democracy in Iraq Was 'Unrealistic,' Still a Popular Bipartisan Goal

The former Bush defense secretary's said he's always been uncomfortable with the democratic rhetoric.

In an interview with the Times of London, Donald Rumsfeld, secretary of defense during the first six years of the Bush administration, said that administration's goal of democracy in Iraq as "unrealistic" and that President Bush had been wrong to adopt that strategy. CNN pulls a quote getting a lot of attention:

"I'm not one who thinks that our particular template of democracy is appropriate for other countries at every moment of their histories. The idea that we could fashion a democracy in Iraq seemed to me unrealistic. I was concerned about it when I first heard those words," Rumsfeld told the Times of London last weekend.

The comments, CNN claims, mark a "rare departure" for Rumsfeld. Here's Rumsfeld describing his stance on democracy in Iraq in the run up to the war in his 2011 memoir, Knowns and Unknowns:

If we hurried to create Iraqi democracy through quick elections, before key institutions--a free press, private property rights, political parties an independent judiciary--began to develop orgnaically, we "could end up with a permanent mistake--one vote, one time--and another Iran-like theocracy," as I wrote in a May 2003 memo.

Rumsfeld wrote that he suggested "the administration soften the democracy rhetoric" and "talk more about freedom and less about democracy, lest the Iraqis and other countries in the region think we intended to impose our own political system on them, rather than their developing one better suited to their history and culture."

In fact, in his memoir, shifts the blame for the rhetoric to Bush and/or Rice. "It was hard to know exactly where the President's far-reaching language about democracy originated," Rumsfeld wrote. "It was not a large part of his original calculus in toppling Saddam's regime."

Bush's memoirs, Decision Points, written in sections about specific decisions, place the threat of weapons of mass destruction front and center as the reason for the war. "The only logical conclusion was that [Hussein] had something to hide, something so important he was willing to go to war for it," Bush wrote while defending his decision to go to war as a last resort to deal with the Iraqi dictator's refusal to submit to demands on weapons inspections.

In Decision Points, Bush also cites the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998, signed into law by President Clinton, which made regime-change and democracy in Iraq a U.S. foreign policy goal. As for Rumsfeld's preference for "freedom" over "democracy," Bush appeared to have adopted or accommodated it when ordering the invasion of Iraq "for the peace of the world and the benefit and freedom of the Iraqi people."

Of course the Iraq war did neither. There were no smoking gun weapons of mass destruction, the Bush administration appeared wholly unprepared to manage Iraq after toppling its government, an eight-year-war led to a precarious strongman "democracy," and now thanks to power vacuums created in part by the American interventions of the last two decades, a significant portion of Iraq, and Syria, are under the control of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), an off-shoot turned alpha to Al-Qaeda, the terrorist group responsible for 9/11 and who, along with "associated forces," are the target in the U.S.'s open-ended "war on terror."

While President Obama has contributed with his own interventions, with assists for Hillary Clinton, the likely 2016 Democratic nominee, it's Republicans who are mostly jockeying to say they're carrying the torch of the Bush interventionist legacy. Last month Jeb Bush and Marco Rubio became the centers of media controversy for their answers to questions about whether the Iraq war was a mistake in hindsight. Of course it was. But it was also a mistake then. There's been more than a decade of other foreign policy mistakes since then, mostly supported by guys like Rubio, and far more bipartisan than partisans would like them to appear. The presence of so many pro-Iraq war presidential candidates, from Hillary Clinton to most of the Republicans not named Rand Paul, illustrates that bipartisanship.

Rumsfeld tried to resign at least twice during his six year tenure as secretary of defense. His successor, Robert Gates, served into the Obama administration. Democratic regime-change, from Libya to Syria, remains a seldom questioned bipartisan establishment foreign policy goal, the occasional attention given former officials who used to be decision-makers notwithstanding.

Show Comments (47)