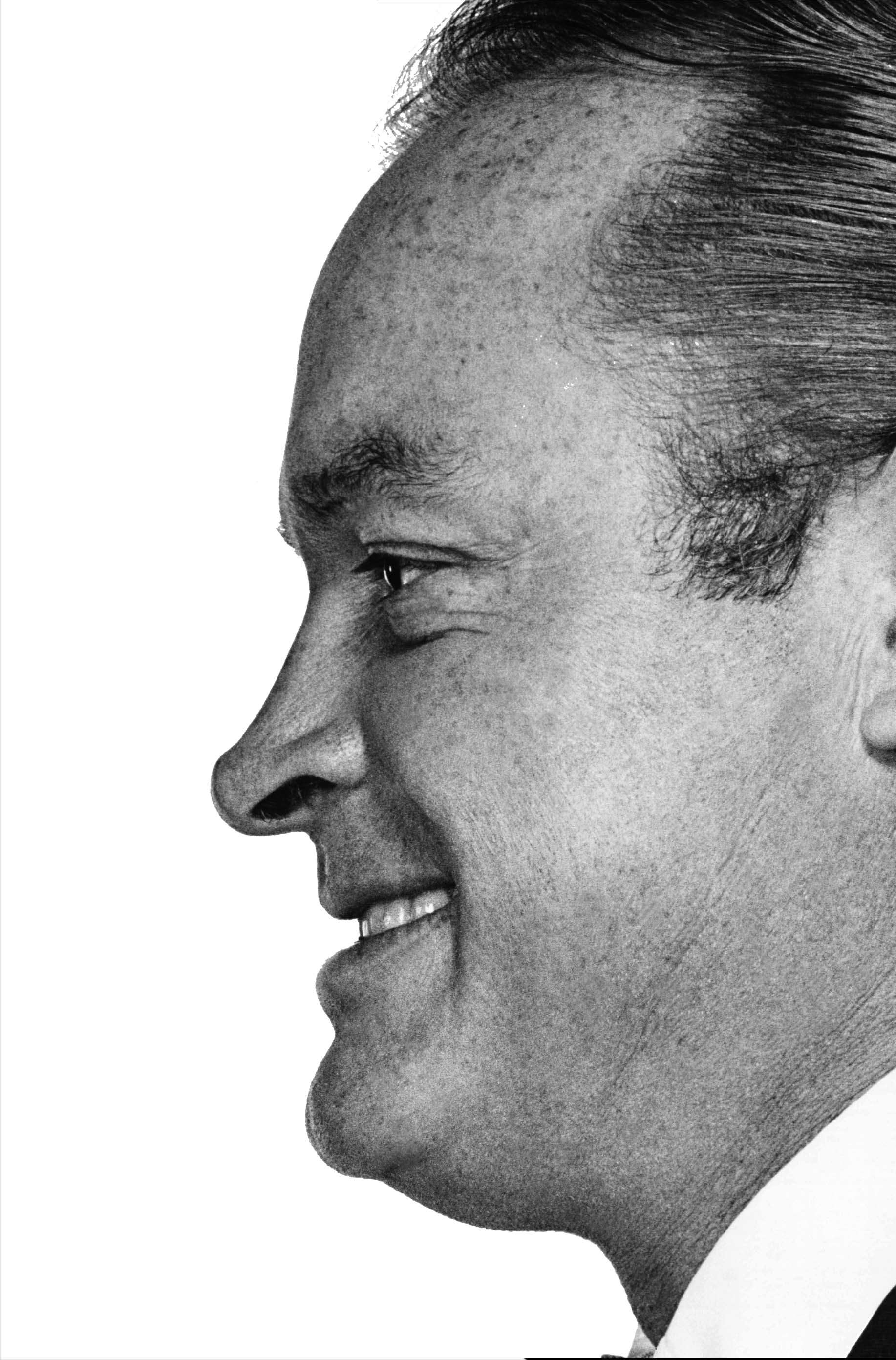

Bob Hope's Journey

How a broadly popular performer became a symbol of cultural and political division

Hope: Entertainer of the Century, by Richard Zoglin, Simon & Schuster, 565 pages, $30

Bob Hope lived to be 100. For most of those years he was one of the biggest celebrities in the world. But what mark has he left? Journalist Richard Zoglin tries to answer that question with his biography Hope: Entertainer of the Century. It's the subtitle that intrigues—does Hope deserve the designation, and if so, what will people make of him in this century?

Zoglin's previous book was Comedy at the Edge: How Stand-up in the 1970s Changed America, so it's interesting to see him take on the man who helped create the world those comedians were reacting against. Long before Richard Pryor or George Carlin were performing, Hope was actually hip: When he was new on the scene, he offered something fresh and different that audiences couldn't get enough of. Zoglin, better than anyone before him, shows us how Hope built up that character to become a huge star, beloved for decades and yet at times surprisingly controversial.

That controversy was probably inevitable. It's not so much that Hope changed—though he did, somewhat—but that the audience did. When the comic was coming up, performers who wanted to hit it big knew they couldn't go wrong waving the flag. But in an era of clashes over civil rights, Vietnam, the counterculture, Watergate, and more, it became hip to paint yourself as outside the mainstream, no matter how successful you actually were. Questioning the most basic aspects of our society signaled to the new audience that you were one of them. Hope, being the most noticeable and unembarrassed representative of an older type of entertainment, indeed an older type of America, was bound to come in for his share of denunciation. But inevitable or not, it would be a mistake to let the controversy get in the way of assessing Hope's work and its influence.

Though he would become almost ostentatiously American, Leslie Towns Hope (he'd change it to Bob for show biz) was born in London, England, in 1903. His family emigrated to Cleveland before he turned five. He and his six brothers were raised in poverty, learning to scramble to make it. Even when he became the richest entertainer in the world, he still retained a certain stinginess—he could be very generous to old friends, but he would fret if he felt he wasn't getting the best deal, even over small things.

After bouncing around from one job to another, including a stint as a boxer, Hope went into vaudeville in the 1920s. He started as a dance act but found he had talent as an emcee, which turned him into a comedian. In this role he was a trailblazer, one of the earliest entertainers to do stand-up routines as we understand them today. Before then, a comic generally had an artificial persona and performed prepackaged jokes and routines. Hope helped introduce and develop a more casual, spontaneous, and topical style-ironically paving the way for the comedians who would later dethrone him.

The Depression didn't slow Hope down, and he made a smooth transition to Broadway. As a Broadway star, he wasn't sure he needed Hollywood, but he signed with Paramount and moved out west in the late 1930s. He made a splash in his first feature, The Big Broadcast of 1938, introducing what would become his theme song, "Thanks for the Memories." The next several films didn't show him to the same advantage, but then, in late 1939, came The Cat and the Canary, a comedy mixed with a murder mystery. It's here we start to see the classic Bob Hope character really emerge: a brash coward who talks in wisecracks.

His next film, Road to Singapore, released in 1940, was equally important. The hit film teamed him up with his old friend Bing Crosby, and over the years six more Road pictures would follow. (Hope was planning yet another when Crosby died in 1977.) The series soon found its formula: Hope and Crosby played vaudevillian con men who'd travel to some exotic location, get involved in an adventure, sing a few songs, woo co-star Dorothy Lamour, and crack a lot of jokes. While Singapore is played relatively straight, the later films were all about the gags—often supplied as "ad libs" by their personal writers—while the story was almost an afterthought.

Hope was now a star, appearing on the top 10 list of Hollywood moneymakers for 13 consecutive years from 1941 to 1953, topping the list in 1949. He became a major figure in Hollywood, hosting the Oscars 19 times—more than twice as many as second-place Billy Crystal. He made comedies almost exclusively, but in various genres: spy films, period pieces, Westerns, etc.

Meanwhile, he got into radio and became its top star. Not unlike his movies, his radio performances were mainly about the jokes, the more topical the better. He went through more material than almost any other performer, and he kept a large stable of gag men who wrote to order. Though Hope had a quick wit and could ad lib with the best of them, he was highly dependent on his writers. They were on call at all hours and could be woken up if Hope needed some funny lines for the VIPs he was golfing with the next day.

During World War II, he also started entertaining the troops. This became something he'd be associated with for the rest of his career. More than once he was close enough to the fighting to have to take cover during an air raid. But he would go anywhere to do these shows. A few decades later in Vietnam, Zoglin reveals, he was running late and arrived at the aftermath of an explosion that, it was discovered, was meant for him.

As old-time radio was dying, Hope switched to the medium that was killing it: television. In fact, in 1947 he hosted the first commercial TV broadcast in Los Angeles, when television sets in the city numbered in the hundreds. Television grew quickly, and while many in movies saw it as the enemy, Bob became a mainstay at NBC. He never had a weekly show, but he hosted numerous hours, generally in the variety format. His specials were often the highest-rated broadcasts of the year, and he continued putting them out into the 1990s.

But it's hard to stay on top. Like any performer, especially a comedian, Hope was always in danger of becoming old-fashioned. When he first appeared on screen, his quicksilver style and up-to-date gags made him an exciting and novel presence. But the audience can burn out on anyone, and comedians often lose a step as they get older. By the late '50s, Hope was part of the old guard-still popular, but no longer cutting edge. His films were getting a little tired, and the receipts started dropping off. His TV appearances were still a big deal (TV demographics skew older), but by the '60s his small-screen efforts were also suffering from age, with Bob mocking beatniks and bra burners. (Not that Hope's personal tastes were necessarily stodgy. He was a fan of Lenny Bruce; he just would never put him on one of his shows.) With the era of sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll on the rise, Hope found himself on the wrong side of the generation gap.

Along the way, he got on the wrong side of a political divide, getting attacked for what he saw as simple patriotism. There's little evidence that Hope saw himself as particularly political, and he kidded politicians of all stripes. But he did become more conservative as he got older, or perhaps his innate conservatism became more obvious. In the Vietnam era, it made him a lightning rod.

In the 1940s, entertainers had unquestioningly supported World War II. In the 1960s, when Hope strongly supported the war in Vietnam, he not only got pushback from protesters but even started hearing occasional boos from the troops. Entertaining the First Infantry at Lai Khe in 1969, he spoke positively of President Richard Nixon's war plans and was, by most accounts, driven from the stage by the negative reaction. After the war was over, tempers cooled, and most of the political hassles were put behind him. But there was always a portion of the country that didn't forget and saw him as a reactionary.

Hope continued working into his 90s, reaching audiences on TV and in person but not getting the critical approval that was once his. Did it bother him? He was a revered institution, world ambassador, and friend of presidents, and that may have been enough. (He was also a philanderer, but his wife Dolores put up with it so it didn't affect his public persona.) In what must have made Zoglin's research difficult, it's hard to know much about Hope's inner life-if he had one, he was too glib to let most people in on it. But the one thing he apparently needed was to be in front of an audience, and that's something he did for as long as his body let him.

Bob Hope died in 2003, after he turned 100. Was he, as Zoglin puts it, the entertainer of the century? Well, he rose to the top at everything he tried—vaudeville, Broadway, radio, movies, TV, and personal appearances. He even was a significant singer, introducing such standards as "It's De-Lovely" and "Buttons and Bows," and he wrote (or signed, anyway) several bestselling books. If not Hope, then who?

But how will this star of the 20th century appear to the 21st, and beyond? Looking back at his TV specials, they have a certain nostalgic charm but not much else. It's his movies, at their best, where he stakes his claim to immortality. Titles such as Monsieur Beaucaire, My Favorite Brunette, and The Paleface, not to mention his Bing Crosby pictures like Road to Morocco and Road to Utopia, may not be all-time classics, but they can still make an audience laugh. And what makes them work—rising above the movies themselves—is the character Hope invented. Hope as a clown may not quite have the depth or resonance of a Groucho Marx or a W.C. Fields, but his comic style makes him indelible. He's a direct inspiration to such big names in comedy as Woody Allen, who channels Hope in films like Love and Death, and Seth MacFarlane, who sings a parody of "Road to Morocco" in an early episode of Family Guy.

If anything, Hope is underrated because he makes it look easy. It may seem he's merely spraying out one gag after another, with his writers doing the heavy lifting, but it takes years of experience, not to mention a unique charm, to pull that off. It's the delivery: slick, but never oily. And the pace: brisk, but full of sly pauses and double takes. And the tone: light, but ready to strike hard at any moment. And the attitude: a character who thinks he's a step ahead, only to discover the joke's on him. On top of which, he's got a dancer's grace, whether doing physical comedy or just leaning into a line.

So will he live on? Probably. Tastes change, but funny is funny—and future generations are less likely to care how he felt about the Vietnam War. And if the fans to come want to find out the story behind it all, it's hard to imagine a better place to start than Zoglin's book.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Bob Hope's Journey."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Bob Hope and Johnny Carson were perfect comedians. Not to say that there aren't any good comedians nowadays, but Hope and Carson had perfect timing.

Carlin never recovered from his hatred of Reagan. Occasionally, his later rant-based comedy produced some genuine laughs, but it paled in comparison to A Place for My Stuff.

I remember as a little kid a Carson show with Hope, and several other big names of that era. It was like crosby, Sinatra, Sammy Davis, jr. etc etc. They all three or four walked out on stage *unexpectedly it was claimed* drunk as skunks. One of them was smoking while sitting on the couch and would really dump his ashes in anothers drink glass when he was talking to Johnny. Everyone knew it except the one who kept drinking out of the glass.

One of the best Carson's ever was when ZaZa Gabor was on the couch with a cat on her lap. She asked Johnny if he would like to pet her pussy. Without hesitation he replied, " If you would move your cat I would be happy to (paraphrase) ". That's not much in the age of free porn but it was was racy shit back when we only had three channels of broadcast TV.

Ha!

I dont remember where i read it, but I recall that Carson hated Bob Hope as a guest because he wasnt conversational and would insist on reciting his scripted bits. Apparently Hope was only on so much because the network forced him to.

Also, The Fiends:

Die Bob Die!

You Sugarfree'd the link.

Entertaining the First Infantry at Lai Khe in 1969, he spoke positively of President Richard Nixon's war plans and was, by most accounts, driven from the stage by the negative reaction.

He should have led with a joke about child molestation and Mounds bars. But Hope knew those V's they were flashing weren't peace signs, they were WWII victory signs.

I guess "Snore" is le mot juste for this one.

Hope was a very funny guy, and I liked him a lot. However, I have heard one thing that disappointed me. I think it was while making My Favorite Spy that he realized that Hedy Lamarr was getting a lot of laughs, and demanded that the script be changed so that he looked better. It was a churlish and ungenerous thing for him to do. He was already a huge star, and her later career might well have been better had her ability to do comedy been on better display in that film.

And no discussion of Bob Hope is complete without a mention of his role as secret Illuminati master of a global MK-Ultra Mind Control slave troupe!!1!

You might be some kind of a weirdo. The idea that he would have enjoyed and allowed some production to use his name/talent and leave him worse for wear is really nutty.

"Hey, I noticed you wrote his character pretty well, but wrote mine like crap. I'm Bob Hope. Fix it."

"Hey I noticed you made his costume pretty well, but mine looks like crap. I'm Bob Hope. Fix it."

"Hey I noticed you raped his face pretty well, but mine remains chaste. I'm Bob Hope. Fix it."

Ah, Hollywood.

Supporting the plan that would ultimately disentangle the USA from Vietnam and which was three years later the centerpiece of a 49 state landslide makes on a reactionary?

IMO, one reason for Hope's success was his quick mind and his ability to improvise. I saw him live one time. He was the half-time entertainment at a home coming game at the university I want to. All his jokes were about the game, the team, the university, the city and the state. Everything was funny and spot on. I couldn't believe how good he was. I think people tend to underestimate his talent.

Is that irony, or do you really think writers wouldn't've produced such topical material?

I wonder if Andy Breckman ever wrote for him.

It seems to me that the people who disliked Hope (as opposed to not happening to find him funny) were political ideologues who judged everything on the basis of whether it helps or hurts their agenda. No one should ever miss such "fans".

The worst element of the Bruce/Carlin/Pryor/etc. type was how comedians have to spew propaganda and that comedy has to serve some political or cultural agenda.

Especially when somebody like Mort Sahl could be political, funny, & not tall into that trap.

When I was a little kid, Hope gave the address at my oldest brother's graduation. My middle brother told me that Hope was referred to as "Old Ski Nose". Not knowing any better (I was maybe 6 at the time), I hollered out "There his is, Old Ski Nose" as Hope was coming down the aisle to be introduced. To his credit, from what I'm to understand, he handled the situation with grace noticing the comment and laughing.

He called himself that.

Start making cash right now... Get more time with your family by doing jobs that only require for you to have a computer and an internet access and you can have that at your home. Start bringing up to $8596 a month. I've started this job and I've never been happier and now I am sharing it with you, so you can try it too. You can check it out here...

http://www.jobnet10.com

The Crosby Show starring Malcolm Jamal Warner

My dear, the next five minutes can change your life!

Give a chance to your good luck.

Read this article, please!

Move to a better life!

We make profit on the Internet since 1998!

............... http://WWW.WAGE-REPORT.COM

Provocative title for the book. Obviously wrong. Mel Brooks is an obvious comparison who will be remembered long after Hope. Hope is like Carson and Letterman. Great for immediate consumption. Gone tomorrow. Nothing wrong with that. Good work if you can get it.

Come on! One of you rich libertarians pony up and buy Bob's old digs. The place is fucking amazing.

http://www.zillow.com/homedeta.....9489_zpid/

It's a cool place, but $286,356 in property taxes every year, yikes....

I also remember an amusing piece in Spy magazine 20+ years ago. The writer was given a ride by the elderly Hope on some winding roads, worried about dying in a crash, and imagined headlines reading: "Bob Hope Dies in Crash with Unidentified Male Companion."

Seriously? A fluff piece to promote a book about an almost entirely irrelevant comedian? I am astonished at how displaced this article is from the generally topical, interesting, and libertarian-minded offerings from Reason. I guess Zoglin must be a good buddy of Kurtz's.

We each know the funniest person in the world. He?it is more often a he than a she?is someone in your family, your business, maybe your neighborhood. His jokes are set up by your shared experience. He has a vast head start over the standup comic.

..

The standup comic is a stranger. From a standing start, he has to generate laughs without their having been set up like the funny people we know. That's something to appreciate.

Start your buissnes from home!

Grow a second income and become your own boss!

For a better future! CHECK FREELY t............ http://WWW.TIMES-REPORT.COM

Nathaniel . although Stephanie `s rep0rt is super... I just bought a top of the range Mercedes sincee geting a check for $4416 this last four weeks and would you believe, ten/k last-month . no-doubt about it, this really is the best-job I've ever done . I actually started seven months/ago and almost straight away started making a nice over $79.. p/h..... ?????? http://www.Jobs-Cash.com

Start making cash right now... Get more time with your family by doing jobs that only require for you to have a computer and an internet access and you can have that at your home. Start bringing up to $8596 a month. I've started this job and I've never been happier and now I am sharing it with you, so you can try it too. You can check it out here...

http://www.jobnet10.com

Nathaniel . although Stephanie `s rep0rt is super... I just bought a top of the range Mercedes sincee geting a check for $4416 this last four weeks and would you believe, ten/k last-month . no-doubt about it, this really is the best-job I've ever done . I actually started seven months/ago and almost straight away started making a nice over $79.. p/h..... ?????? http://www.netcash9.com

Start making cash right now... Get more time with your family by doing jobs that only require for you to have a computer and an internet access and you can have that at your home. Start bringing up to $8596 a month. I've started this job and I've never been happier and now I am sharing it with you, so you can try it too. You can check it out here...

http://www.gowork247.com