Four Reasons US Intervention in Nigeria Is a Bad Idea

Superpowers can't be superheroes

Earlier this week the Nigerian government accepted an offer from the United States that involved deploying a special security team to participate in the attempted rescue of nearly 300 girls kidnapped last month by the Islamist extremists Boko Haram. The girls were taken from a government school in Chibok. About fifty girls were able to escape the kidnap attempt, and provide details about how the kidnapping took place. One girl said the Boko Haram men told them they were soldiers and that nothing would happen to them. Then they set fire to the storage room and started shouting "Allahu Akhbar," according to the girl, who said it was then they knew what was actually happening.

The U.S. government first offered help this month after the story of the kidnappings broke into mainstream media in the West. Nigeria's president, Goodluck Jonathan, was initially reluctant to accept international help. On Tuesday Jay Carney, the White House press secretary, said he took Jonathan's "welcoming" of a U.S. offer as an acceptance, even though he didn't "speak for the Nigerian government." Carney stressed, too, that the Nigerian government had to make sure it was doing everything it could in the situation. Jonathan finally "accepted a definite offer of help" from the United States. The U.S. will be sending a special rescue team to aid the Nigerian government, but the State Department says it will not include any commandos or special forces, although it will include a small military team. Nevertheless, on the Today show President Obama called U.S. aid in rescuing the kidnapped girls a "short term" goal, and said the United States would also "have to deal with the broader problem of organizations like this that can cause such havoc in people's day-to-day lives."

Arguably the U.S. would not have put as much pressure on Nigeria to accept its aid were it not for the popular outrage over the horrific crime. Nigeria's president himself didn't comment on the kidnapping until this weekend, nearly three weeks later. Now he says it will mark a turning point in his country's war on terror.

And while the offer of limited U.S. help may alleviate the understandable outrage over the kidnapping, even if it can't significantly improve the chances of rescuing the girls, broader U.S. intervention in Nigeria, no matter how benevolent-minded in this particular instance, is a bad idea all around. Here's why:

It's bad for Nigeria

Boko Haram has waged a campaign of terror in northern Nigeria for the better part of the last five years, for the entirety of Jonathan's term as president, and Jonathan has been criticized for his lack of control of the broader situation. The kidnapping of nearly 300 girls may have been unprecedentedly brazen, but Boko Haram commits kidnappings, murders, and lootings on an almost daily basis. Earlier this week as many as 300 people may have been massacred by Boko Haram in a town along the border with Cameroon.

In the aftermath of the mass kidnapping, the Nigerian government first insisted it had rescued the girls before admitting it had no idea where they were. Nigeria's first lady wondered if the incident hadn't been staged in an effort to embarrass her husband.

In an open letter to Americans, Compare Afrique co-founder Jumoke Balogun writes that the popular call for U.S. involvement in the kidnapping "undermines the democratic process in Nigeria and co-opts the growing movement against the inept and kleptocratic Jonathan administration." Balogun writes that it was Nigerian outrage that forced President Jonathan to act, and that Nigerians had to hold Jonathan and the government accountable in the crisis. American emphasis on U.S. action, Balogun insists, "only expands and sustain[s] U.S. military might."

Indeed U.S. involvement has the potential not only to lower the pressure on Jonathan and the Nigerian government's responsibility to establish order in the north but at the same time to permit Jonathan to harness the "rally around the flag" effect without taking the necessary steps to form more effective policies to deal with the wider Boko Haram campaign

It's bad for Africa

The wider Boko Haram campaign has been bad for the region and its people too. Indeed, some believe the kidnapped Nigerian girls have already been taking to neighboring countries. The intelligence chiefs from the member countries of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) will meet in Ghana to discuss the security situation in northern Nigeria, although ECOWAS has so far done little more than pledge "solidarity" with Nigeria. The same is true for the intracontinental African Union (AU), which issued a statement last week which expressed "solidarity with the anguished families."

Yet ECOWAS and the AU are attempts by African countries to build the kind of regional organizations that could, through cooperation and international governance, help promote security and stability on the continent. "Every asset and expertise should be brought to bear," former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said this week in comments about the kidnapping. "Everyone needs to see this for what it is, it is a gross human rights abuse but it is also part of a continuing struggle within Nigeria and within North Africa." She called Nigeria's government "somewhat derelict" in its responsibility to protect children, and urged the international community, Nigeria's neighbors, and the AU to stay involved in the crisis.

But why would ECOWAS or the AU step up when the U.S. can be prodded into doing the work?

It's bad for the United States

The United States has long considered Boko Haram a terrorist organization. Nevertheless it was a regional group that therefore didn't fall under the rubric of the "war on terror by another name." Members of Boko Haram have already killed hundreds of people since last month's kidnapping and a broader U.S. intervention would drag America into the regional unrest and continue an American legacy of disastrous intervention in North Africa. Remember, the 2011 intervention in Libya that toppled the government of Colonel Moammar Qaddafi also resulted in thousands of weapons going missing. Those have made their way throughout the wider region, to Mali, where they contributed to a deteriorating security situation into which the French led a military intervention, and from Nigeria to Syria.

The U.S. Congress, meanwhile, focuses on the deadly 2012 attack on the U.S. mission in Benghazi with almost no regard for how the military intervention in Libya it did nothing to stop contributed to the situation. House Republicans insist the Obama Administration minimized and misrepresented the terrorist nature of the 2012 attack without addressing how the U.S. intervention in Libya created the opportunity for Al Qaeda and Al Qaeda-linked affiliates to flourish there in the first place.

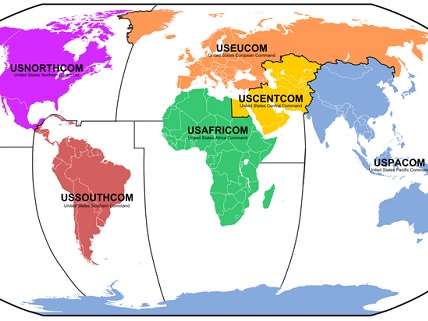

The longer term inclusion of Boko Haram in U.S. counterterrorism policy President Obama alluded to on the Today show won't come with an accounting of how the intervention in Libya may have helped to fuel Boko Haram's campaign, but it will provide another reason for the U.S. to expand its military footprint in Africa and extend the fiction that the United States has the means, resources, and moral and political capital to remain the world's policeman indefinitely.

It's good for Boko Haram

Drawing the United States into the conflict could be exactly what Boko Haram wants. By engaging the United States, the group is signaling to the Nigerian government that it is beyond its purview, that it's presented a credible enough claim on control in Nigeria to elicit U.S. attention and a U.S. response. Boko Haram has been reported to loosely mean "Western education is forbidden." Dan Murphy at The Christian Science Monitor took issue with that, tracing the definition of boko to a description of the imposition of a foreign, non-Islamic, in that case British, or Western, education on the Hausa people.

Today, then, boko might extend to the authority emanating from Abuja, the Nigerian capital. Boko Haram wants a fight with the West and with the United States (and former colonial power the United Kingdom, which is also offering assistance) because such western intervention helps it to demonize the Nigerian government it seeks to depose. Nurturing a reliance by the Nigerian government on western assistance to impose order in the north, meanwhile, diminishes the Nigerian government's strength in relation to Boko Haram, which has grown from a local Islamist militant group to designation as a foreign terrorist group by the U.S. State Department in 2013, when the department warned of Al Qaeda links. "Proving" itself in the eyes of Al Qaeda by executing a brazen attack that the Nigerian government appears powerless to respond to without outside help could even lead to strengthened ties between Boko Haram and the amorphous global terrorist organization.