Barry Commoner: The Sunshine Candidate

Does bad science make good politics?

Notable among this year's "other" candidates is Dr. Barry Commoner, biologist turned solar-energy advocate. Commoner is running for president under the banner of the Citizens Party, a leftist coalition organized for the event by himself and friends, and including Mario Savio, Julian Bond, Studs Terkel, and vice-presidential candidate La Donna Harris. Solar energy and economic democracy are leading themes of the Citizens Party platform, which calls for public control of the energy industry, a swift halt to nuclear power, and a strong push for conservation and solar energy. Commoner himself, in his latest book, The Politics of Energy, argues that solar energy is by nature a public good, incompatible with the private, profit-oriented institutions of capitalism, and so requiring public support and direction.

A very articulate man, and renowned for being a scientist, Commoner has succeeded in attracting considerable attention to his candidacy. The Village Voice led the media in touting him as a plausible leftist alternative to this year's major-party offerings. Bill Moyers' Journal has lionized him. His books on energy have been popular and were serialized in the New Yorker. He is an engaging speaker and a hit on the campus speaking circuit. His political activities have sparked interest in the scientific community and have been covered in the pages of Science and Nature.

It is Commoner's work in biology, though, and not in energy economics, that is the basis of his scientific reputation. By his own account, he has never had a course in economics. And now, his tendency toward public advocacy has come to compromise his reputation as a biologist.

"Commoner is in a way always doing too many things," says one prominent Berkeley biologist. "I don't think that any scientist that really knows his work respects him that much." Other scientists confirm that Commoner has a reputation more for publicity than for science, using the ideas of others to draw overly broad and unwarranted conclusions and being "too eager to prove his case."

Even many serious environmentalists and solar-energy advocates have joined the ranks of Commoner's critics. Prominent among them is Prof. John Holdren of the University of California at Berkeley. A leading opponent of nuclear energy, Holdren complains, "The problem with Commoner is that on many issues he is half-right, but the other half is nonsense."

Holdren's disagreements with Commoner date back to 1972, when he and Paul Ehrlich, the noted Stanford biologist, wrote a scathing review of Commoner's best-selling book on ecology, The Closing Circle, for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Upset by what they saw as a "one-dimensional" view of ecology that overemphasized pollution to the neglect of population and economic growth, Ehrlich and Holdren charged Commoner with using "biased selection of data, unconventional definitions, numerical sleight of hand, and bad ecology." In a lengthy but evasive reply, Commoner did everything but refute these charges.

Commoner's first book on energy, The Poverty of Power, met with similar criticism, this time at the hands of the eminent economist Kenneth Boulding, a liberal and judicious scholar who is widely celebrated for his pioneering work in ecological economics. In a withering review for Society, Boulding denounced The Poverty of Power as a "very bad" and "dishonest" book, "a political tract disguised as a scientific statement," with "logical fallacies on almost every page."

In the light of this record, it is perhaps surprising that Commoner was invited to speak on energy and economics before the American Association for the Advancement of Science (of which Boulding, ironically, was then president), at its convention in San Francisco earlier this year. Energy, however, is a popular topic in scientific circles these days.

Commoner acted the part of the politician, taking occasional potshots at President Carter, the Department of Energy, and the oil companies. Except for a handful of hostile questions, his performance was not ill-received by the audience. He was, of course, popular with the not inconspicuous minority of activists calling itself "Science for the People."

His scientific contribution to the conference was more questionable, however. Although he took part in three different panel discussions, unlike many participants he did not contribute any original paper to the proceedings. Rather, with more than a little repetition, he reiterated his standard campaign material, virtually all of which was familiar to me from a lecture I had heard him deliver nearly two years previously at Stanford. Even his slides were the same.

ENERGY ALTERNATIVES Commoner's argument is set forth in his latest book, The Politics of Energy, a slick, popularly written political tract. It begins with the proposition that our present economic system is "cannibalizing itself"; that as long as we are dependent on exhaustible fossil fuels, the cost of energy will rise "exponentially," causing continued inflation and economic distress. The only way out, he deduces, is to go to an entirely renewable energy source, such as solar energy or the breeder reactor. Of these, Commoner is convinced that solar is the only safe, clean, "politically acceptable" alternative, and he has accordingly designed a unique, decentralized, all-solar energy system for the nation.

Unfortunately, however, Commoner does not think his scheme can be realized within the framework of a market economy, on the grounds that existing economic institutions are guided by private, rather than "social,", profits. Just what social profits are, he never explains, but he does claim that it will be necessary to impose public control on the energy industry through a system of "social governance." Again, Commoner does not explain what social governance is, other than to suggest that it is related to "economic democracy."

For all its vagueness, Commoner's discussion of energy alternatives is by no means implausible on first hearing, and he is skillful at making it sound convincing to an unsophisticated audience. Frequently, he introduces it with a simplistic but amusing "short course in thermodynamics," in which he defines such concepts as work and energy in the manner of a good junior high school science teacher. It is all very elementary and unexceptionable, and it gives a pseudoscientific air of exactitude to what follows—the utterly fallacious proposition that energy costs rise "exponentially."

This, according to Commoner, is the one "absolutely essential idea" for understanding the energy crisis: as nonrenewable fuels are depleted, the cost of producing them will rise exponentially, forcing up energy prices accordingly. Exponentially, of course, is an impressive-sounding word coming from the mouth of a scientist. In contrast to all of Commoner's vague utterances, however, exponentiality is a precise, mathematically defined relationship whose implications can be easily tested.

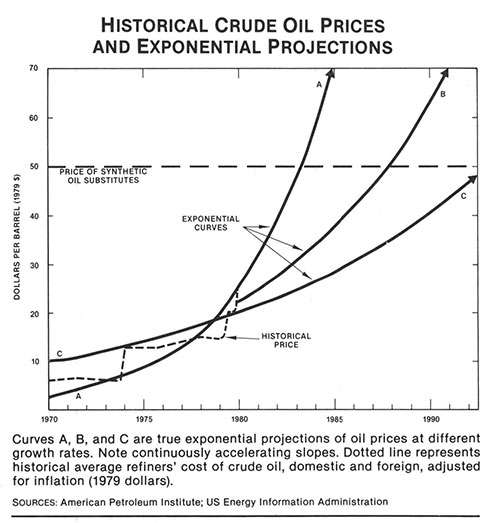

Take, for instance, the recent trend in the price of oil. The law of exponential growth would require that oil prices continue to rise at the same rate, like compound interest, into the indefinite future. And since the average price of crude oil in the United States has risen some 250 percent over the past six years (adjusted for inflation), this would mean a projected average price of $75 per barrel of crude oil by 1986, $275 by 1992, and $1,000 by 1998 (see Curve A, above). The last figure is obviously absurd, but even the first is improbably high, since a vast supply of crude oil substitutes—alcohol, synthetic fuel from coal, shale oil, etc.—becomes economically competitive at prices of around $50 per barrel. Far from rising exponentially, the price of liquid fuels is likely to stabilize around this level, effective well through the next century.

Where does Commoner's claim come from, then? He rests his case on analogies—for example, between pumping up oil and eating spaghetti. The idea is that, as one gets toward the bottom of the plate, spaghetti becomes "exponentially" more difficult to eat. Whether this is so, and what it says about the cost of oil, are left to the reader's imagination. Few petroleum geologists, however, subscribe to the spaghetti theory of oil. And the facts about oil are that production costs tend to level off, rather than increase exponentially, as new reservoirs are opened up.

QUESTIONABLE CURVES Commoner, of course, does not dwell on the evidence of recent energy prices. This evidence does not support his claim (see the figure on p. 39.) Once at the AAAS conference, however, while discussing another subject, he happened to display a slide on which the historical "price of energy" had been plotted as a curve, lurking alongside other data. Those who noticed it may have seen that the price had risen, not exponentially, but rather in a highly irregular manner that was, if anything, suggestive of a stock market chart. Commoner did not refer to this curve until he was ready to change the slide. "As you can see," he briefly observed, "the price rise is clearly exponential." Next slide.

At a later session, Commoner was finally questioned on the subject of exponentially rising prices by Prof. Georgescu-Roegen, a noted theorist on the economics of depletable resources. Commoner completely evaded the question, so I posed it again, pointing out all of the problems I saw. His reply consisted of two points.

First, he indignantly insisted that he was talking, not about the price of energy, but rather about its cost of production. In fact, however, he had repeatedly used the word "price" in his talks and had elsewhere confounded the two terms as if it were a matter of indifference.

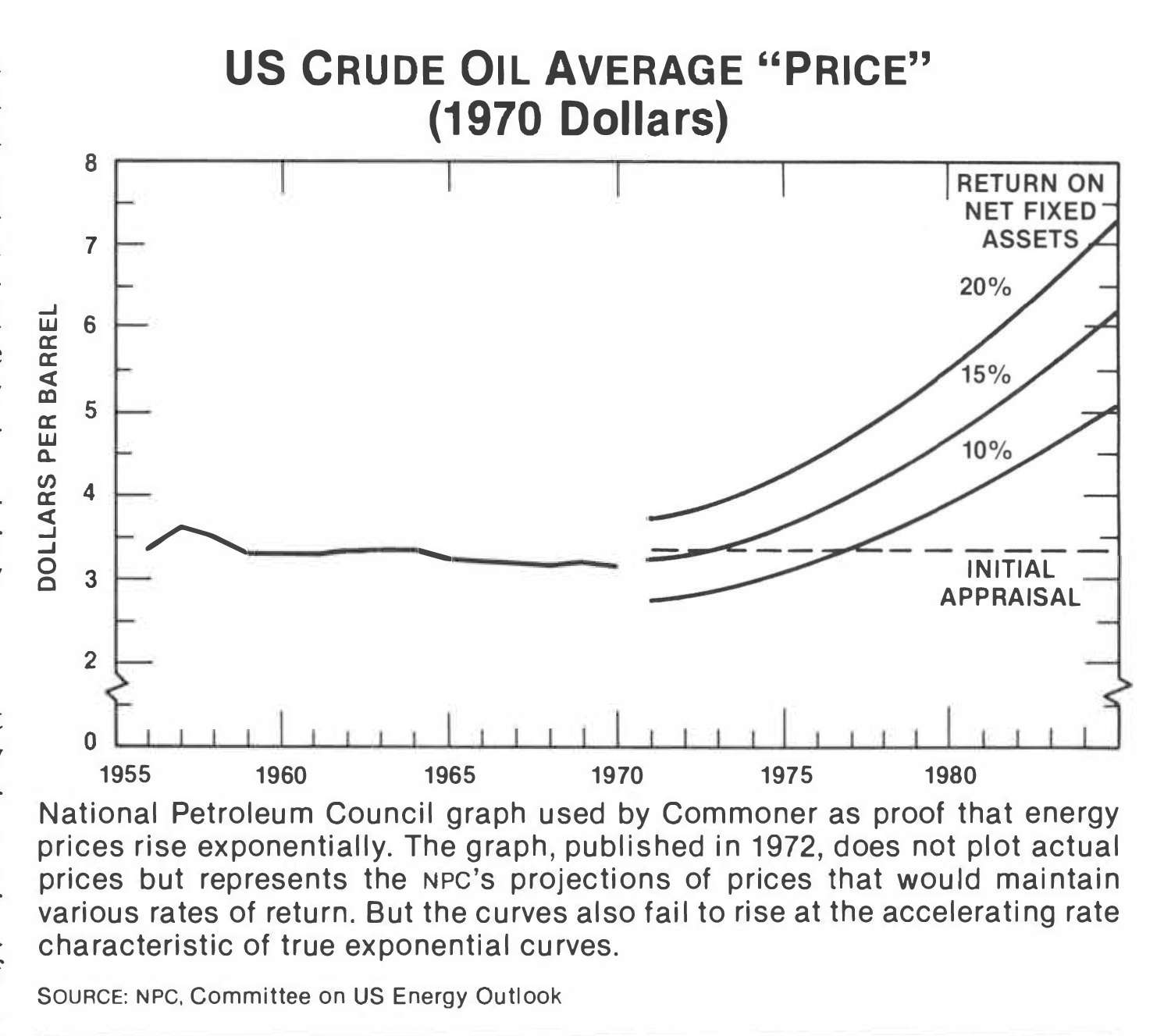

Second, he referred to a graph of the domestic cost/price of crude oil that had been published as part of a National Petroleum Council study in 1972 (see figure above). The graph in question had nothing at all to do with real costs or prices: it represented the NPC's projections of what prices would be necessary if the industry were to maintain various specified rates of return on investment. The result was not one, but a series of curves, rising in a suspiciously ambiguous manner that Commoner was claiming to be exponential.

A later investigation confirmed what seemed likely to me at the time, namely, that Commoner was misrepresenting the NPC's results. As was confirmed to me by those who actually conducted the study, and is evident from an examination of its text, the NPC curves are in no way exponential. On this fraudulent thread of evidence, Commoner rested his case.

This fallacy, while not inconsequential, is just one of many in Commoner's logical house of cards. By arguing that the economy is doomed to be "cannibalized" by exponentially rising prices, Commoner instills a false sense of urgency for abandoning fossil fuels. He then proceeds to limit the discussion to entirely renewable energy systems. Only after he has finally settled on the design of his solar system does he discuss what transition fuels could get us there.

In the meantime, he has greatly simplified his argument by eliminating any examination of such complicating options as coal, shale oil, tar sands, petroleum, or uranium without the breeder reactor. (Commoner classifies the breeder—a nuclear reactor that produces more fissionable material than it consumes—as a renewable technology because the known reserves of uranium are sufficient to last some thousands of years with its use. Without it, however, exhaustion seems possible in a period of decades, and Commoner accordingly treats existing non-breeder nuclear reactor technology as nonrenewable.) Similarly, he is able to slough off any serious consideration of conservation. Claiming that it "misrepresents the fundamental cause of the energy crisis," he is willing to discourage conservation through price controls in order to keep energy prices low.

ARBITRARY DECISIONS In his discussion of renewable energy technologies, Commoner manages to reduce everything to a choice between just two alternatives, the breeder reactor and his own solar plan. In order to achieve this, of course, he must rule out a host of other possibilities, most notably nuclear fusion (in which energy is produced by uniting hydrogen atoms rather than splitting uranium atoms, as in the current fission technology). This he does on the summary grounds that its feasibility has not yet been conclusively demonstrated. "We must be certain of it now," he declares. "We can neither wait for the experiments to succeed nor take the risk of embarking, now, on a transition that depends on their future success."

Why must we decide such matters now? Commoner offers no explanation. Nor does he divulge why, at this particular moment in history, it makes sense to commit ourselves to an all-renewable energy system in the first place. This is perhaps the most crucial fallacy in Commoner's whole program. After all, we have been dependent on depleting fossil fuels for well over a century now. Would we be better off now had we embarked on an all-renewable energy system in, say, 1955, in the heyday of "Atoms for Peace"? If not, why should we do so today, especially if this means ruling out fusion, which is believed by many concerned scientists to carry great potential for energy production from a virtually limitless source—hydrogen.

Commoner is equally arbitrary in ruling out any form of solar energy that does not accord with his own design. In particular, he dismisses all "centralized" solar technologies, such as satellites and power stations, as "inherently uneconomical"—a view for which he again provides no supporting analysis. Ironically, this excludes ocean thermal energy conversion, a technology once touted as a kind of energy panacea by Ralph Nader, who is nonetheless reported to be a Citizens Party sympathizer.

Having finally reduced the universe of discourse to just two energy systems, his own and the breeder reactor, Commoner proceeds to force the choice in his direction:

Is it necessary to choose between the two routes? Can we not follow both of them, emphasizing the advantages and minimizing the hazards of each? Unfortunately, we cannot; the two routes are inherently, intractably, incompatible. The breeder-based system would require the creation of a huge electrical transmission network.…The cost of either system would be so great that the nation simply could not afford to build both of them. We can take one route or the other, not both.

Of course, by the same argument, the existing electrical and gas transmission systems would have to be deemed "inherently, intractably, incompatible." In fact, they are complementary. Commoner has it all backwards; a mixture of energy technologies is virtually certain to be more efficient than a single one alone. In the same way, where it may be prohibitively expensive to build everything out of wood, or out of steel, it may be relatively cheap to build some things of wood and others of steel and some things of both.

Surprisingly, Commoner does not cover any new ground in discussing the relative merits of nuclear and solar power. Instead, he recites all the familiar objections to nuclear energy, as if these spoke for themselves, omitting any reference to equally well known counterarguments. He makes no attempt to put facts into context but plays to his audience's emotions, reciting, for example, the story of a woman who, following her exposure during the Three Mile Island incident, gets physically sick at the thought of radiation, and comparing TMI, jokingly, to a "relatively small nuclear bomb going off on campus."

Sharing the platform with Commoner on one of the AAAS panels, the well-known nuclear advocate Dr. Petr Beckmann noted that the radiation to which the public was exposed at TMI was comparable to what one might receive in traveling to Denver (where natural cosmic radiation is higher because of the altitude). Since Commoner did not dispute this point, one member of the audience rose to ask him whether, as a scientist, he feels any responsibility to inform the public of such facts in order to help people to evaluate the risks of nuclear energy more intelligently. No, Commoner replied with a shrug; he sees no reason to interfere with public opinion in such matters.

With all other alternatives handily disposed of, Commoner is left touting his own unique plan for a nationwide, decentralized, all-solar energy system. This turns out to involve (1) deriving alcohol from crops and methane from biomass conversion, (2) construction of a nationwide methane/hydrogen gas pipeline network, largely replacing the existing electrical grid, (3) decentralized electrical generation from photovoltaic cells, and (4) extensive use of solar heating and cooling, plus other miscellaneous solar technologies.

EMBARRASSING How are we to evaluate the economics of this ambitious scheme? Commoner fails to produce any estimate for its overall cost in capital, labor, or raw materials. While he estimates that the area required for solar energy collectors would be on the order of half that now devoted to roads, he glosses over the fact that his plan would require a 15 percent expansion in land under cultivation. He suggests that the cost of his gas system compares favorably to the cost of electricity but neglects the fact that there is an electrical grid already in place. He also assumes a substantial net energy contribution from gasohol, which many experts would dispute.

Most embarrassing of all, when Commoner finally gets around to considering what fossil fuel would be acceptable as a "bridging fuel" to make the solar transition, the answer turns out to be natural gas. Despite the fact that US natural gas production has been declining in recent years, Commoner's projected gas network turns out to demand, during the 50-year transition period, natural-gas production at an average rate nearly 25 percent higher than presently. This in turn demands somewhat more natural gas resources than are currently thought to exist in the United States. Undaunted by his previous taboo against technologically chancy approaches, Commoner manages to conclude that his transitional system would "in theory" produce enough energy, though "a practical answer is more difficult."

Given such technical flaws, there are few, if any, energy analysts who take Commoner's program seriously. One solar energy advocate minces no words: "Commoner's program is full of biomass," jokes Holdren. On the pro-nuclear side, contempt for Commoner runs so high that few will even bother to try to refute him. One who did is Samuel McCracken, whose critique in Commentary magazine in October 1979 is enlightening.

Especially amusing is McCracken's analysis of a proposal by Commoner to turn on the nation's streetlights via photovoltaic cells. An obvious drawback of this scheme is that all such generation of electricity must occur by day and so requires some kind of storage for night use. In addition, it turns out that, on the basis of his own performance estimates, Commoner has underestimated the required collector area by a factor of 10 and that 1,000 square feet of solar panels are required for every streetlight. Accepting Commoner's own optimistic cost estimates for solar cells, McCracken plausibly estimates the total cost of the proposed nationwide streetlight system to be on the order of $2 trillion. Asked about this, Commoner's only reply is that McCracken's numbers are "back-of-the-envelope calculations"—as if he had done even that much.

Commoner is remarkable in his enthusiasm for photovoltaic electricity. He regularly cites the 1976 federal Task Force on Solar Energy Commercialization, whose projections show the cost of photovoltaic electricity declining tenfold in just three years, given mass production of solar cells. Numbers like this are of course highly speculative and in this case reflect the hypothetical assumption that technological improvements in solar cells will follow the same "learning curve" as electronic semiconductors.

Although most authorities regard the Task Force estimates to be highly optimistic, Commoner refers to them as if they were virtually established fact, going so far as to argue before the AAAS that a guaranteed federal purchase program could give us photovoltaic cells tomorrow "at the stroke of an administrative pen." When I questioned his assurance in this regard, Commoner took umbrage, claiming that these were truly "scientific numbers," the work of the Federal Energy Administration, and that such data were not to be questioned at a scientific conference.

ELITISM BY ANY NAME… As it happens, Barry Commoner is a personable man and may even be sincere, but there were times at the AAAS conference when it seemed hard to credit the sincerity of his politics. Rather, he seemed to play the part of the demagogue, accusing dissenters of various deceits and making it sound as if they are to blame for all of our energy problems. He variously insinuated that the oil companies had held their prices not only too high but also too low and proceeded to blame them for OPEC's own 1973 price hike. The latter accusation turned out to depend on nothing more than the 1972 NPC price study, mentioned above—the notion being that the OPEC leaders got wind of the fact, through the NPC study, that the oil industry was forecasting higher prices, and this put the idea in their heads.

There is a certain political bigotry here, reflecting the vulgar Marxist position that private corporations are by definition bad and constitutionally incapable of acting in the true social interest. Scientist-politicians are, of course, another matter. Not only can they discern what the true social interest is; they can even prescribe entire energy systems for their grandchildren.

This technocratic presumption echoes the work of Thorstein Veblen, another scientifically inclined socialist who pioneered the American technocracy movement some 60 years ago. Veblen, like Commoner, mistrusted business and thought that everything could be run more efficiently by scientists and engineers. It is Veblen who wrote, in a classic moment of excess: "The situation is ready for a self-selected, but inclusive, Soviet of technicians to take over the economic affairs of the country and to allow and disallow what they might agree on."

Today, these words would no doubt be denounced as "elitist" by fashionable leftists. Instead, we read in the Citizens Party manifesto a call for "putting the vast corporations which control our economy under our control" (italics in the original). But who are "we," other than the rather elite and well-educated minority who constitute Dr. Commoner's following and who insist that nothing but solar energy can be in our interest?

What about the rest of us, who may have doubts about the solar option, who have different opinions of the costs and risks, or who have a legitimate interest in some other form of energy? "Society as a whole must be involved," writes Commoner, "for the solar transition is a great historic passage which only the people of the United States can decide to undertake." But why the United States, and not Canada or Cuba? On the contrary, isn't there enough room within our borders for different people to enjoy different energy sources? Shouldn't we have the right to a choice of energy lifestyles?

Commoner has little to say on this, other than to note:

It will also be argued that "social governance" would necessarily impose political constraints that would erode civil liberties and weaken democratic government. This is a serious problem, but the country does, after all, seem to have the wisdom and strength to protect our liberties from erosion or assault. In only the last two decades we have thrown back Senator McCarthy's assault on civil liberties and Mr. Nixon's powerful attempt to subvert the democratic governance of the nation.

It is remarkable indeed, when a minor-party politician offers us the prospect of major-party corruption. It is a shame that Dr. Commoner did not have the wisdom and strength to address this problem more seriously before he embarked on his grandiose energy program. Had he done so, he might have been worth listening to.

Dale Gieringer is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Engineering-Economic Systems at Stanford University. He is doing his thesis on FDA drug regulations.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Barry Commoner: The Sunshine Candidate."

Show Comments (0)