Stamps

Not for kids anymore

Life magazine in 1963 called a rare stamp "the most valuable substance on earth." The stamp thus described was a unique 2¢ Hawaiian Missionary, issued in 1851, unused, weighing 1/2,000 of an ounce. Raymond H. Weill Co., a stamp dealer out of New Orleans, had paid $41,000 for the stamp in 1963 at a public auction. Life has passed away, but the tiny 2¢ Missionary lives and grows. In 1968 the stamp was repurchased for $90,000 after its owner died. It last changed hands in 1970 at $121,000!

While new stamp issues are being mass-marketed and advertised with Madison Avenue gusto, rare stamps are gracefully getting older and becoming rarer. To the chagrin of oldtime philatelists, values are moving skyward. The investment aspect has entered the scene. Serious worldwide inflation, depreciating currencies, and international economic crises are partly responsible. Rare stamps have become an important inflation hedge in the last five years—a store of value with international recognition and marketability. Surprisingly enough, liquidity is excellent, although there isn't a Dow Jones Stamp ticker-tape quotation system…yet.

The price appreciation of rare stamps has a negative side, too. Stamp collecting used to be a quiet, inexpensive hobby for half-pints and retired persons. They could putter around for hours with just a few pennies' investment. But one comment we overheard at a recent stamp show from a 10-year-old collector says it all: "Inflation is killing my hobby. Everything costs $20 and I haven't got $20."

PROFITS IN STAMPS

The U.S. Postal Service has had a lot to do with the fanatical new interest. It's even hired Madison Avenue's Young & Rubicam to spend over $5 million a year to promote philately. Not only are they doing a good job, but the philatelic unit is practically the only profit center in Washington. Everytime a collector buys a stamp at the post office and doesn't use it for postage, the USPS rakes in almost pure profit. According to a USPS survey, 16 million Americans collect stamps.

One bigtime NYSE company has entered the scene. General Mills in 1973 acquired Boston-based H.E. Harris & Co., the world's leading mail-order stamp dealer. Why did General Mills, with $2 billion a year in sales, decide to play around with stamps?

According to Fletcher C. Waller, Jr., director of business development and market planning, "This is a business of inherent stability coupled with appeal to conditions on the rise in the future: extended time to pursue hobbies thru early retirement, a shorter work week, rising discretionary income, and smaller families which offer more capability of indulging individual interests. Stamps have good long term growth potential…even faster growth than our traditional businesses."

In 1974 General Mills also acquired Bowers & Ruddy, one of the largest coin auctioneers and mail-order firms. Waller wouldn't disclose earnings for the stamp and coin divisions, but he conceded that "both are profitable…and in fact more profitable on return than the average of General Mills."

Both H.E. Harris, with General Mills backing, and the USPS, with the government standing behind it, are major pluses for the stamp industry's future potential. Beginner and intermediate collectors add liquidity as they move into the better-grade stuff, so Harris and the USPS may lose some customers moving up the philatelic ladder to the rarities. But the auctioneers and fine-stamp dealers happily take over.

COLLECTING ECONOMICS

Old stamps are a big hit in England, probably for more than philatelic reasons. Inflation is growing there at more than 25 percent annually. Although Treasury bills offer 9½ percent, the yield is negative, given the inflation rate. The value added tax and wealth taxes eat into assets.

But one can buy rare stamps at home in England, without elaborate packing arrangements and without attracting attention. Simply slip them into a pocket or envelope and quietly hop over to Switzerland or Germany for conversion into more stable currencies. Or the stamps can simply be stored in safe deposit boxes in anticipation of higher future prices. A more exotic method of transporting stamps is merely to mail them ahead. Who can forget Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn's discovery in the movie "Charade" of the missing fortune cleverly glued to an envelope? In a world of increasing economic turmoil, crime, and red tape, portability and ease of storage have become significant to investors.

Of course, it's all (or mostly) quite legal in England. Antiques over 100 years old are exempt from the value added tax, and goods under £1,000 in value are exempt from capital gains taxes. Very few items are both exempt and obtainable in sufficient quantities. Stamps are a notable exception.

INVESTMENT POTENTIAL

A review of the H.E. Harris price lists over the years indicates a steady upward climb. For example, in 1944, Harris sold unused Lexington-Concord sets of three stamps for $1.42. In 1975, it was up to $21.95. In 1954, a Famous American plate block set of 35 issues cost $49.50. Now it's $440. That's reaching toward a 1,000-percent rise and will hit it probably in the next year or two. Of course, if you were around in 1925 you could have bought the Lexington-Concord set for 8¢ at the post office or the Famous American set for $5.88 when it was issued in 1940. Neither of these issues is a rarity but because of the tremendous number of new collectors, they're getting scarcer. Naturally, prices are moving upward.

In answer to a query as to whether stamps are recession-proof, Wesley Mann, president of the H.E. Harris division of General Mills said: "When money gets tight, the advanced collector becomes more active. He avoids the stock market and tends to invest his money in collectibles. In the recent recession the number of orders went down slightly but the collecting interest reverted to higher ticket items."

William Amos, a collector since high school and copublisher of Linn's Weekly stamp newspaper, is skeptical of people who look upon stamp collecting as an investment. Nevertheless Mr. Amos admits there's "no question about it, stamps have definitely kept pace with inflation, and it's going to continue. In fact, the new 1976 Scott catalogue for US/UN and British Colonies [released in June] lists over 25,000 new prices on the upside. The trend is looking up." So is Linn's circulation, which reflects the new excitement over stamps. With 10,000 subscribers in 1942, that figure jumped to 60,000 by 1969, and is now 90,000.

Although the Scott valuations are not actual selling prices, they are a reliable market guide and offer comparable year-to-year figures. The condition of the stamps helps to determine the selling price. While a very fine set of Columbians will sell for 50 percent to 100 percent over catalog, poor copies with thins, tears, off-centering, fading, etc. might go for 25 percent to 50 percent under catalog.

PERFORMANCE EXAMPLES

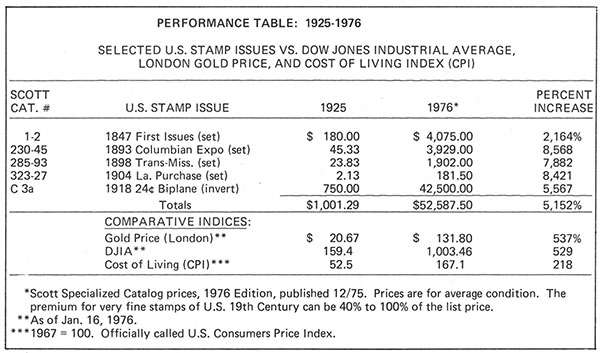

Our 50-year Performance Table going back prior to the depression indicates that the current price action is no fluke, ready to take a dive as have so many other recent investment schemes.

John Wanamaker, Postmaster General in 1893, had the first U.S. commemorative set produced for the 1893 Columbian Exposition. The 16 Columbian issues range from the 1¢ to the $5.00 and are beautifully designed and engraved in single colors. The set was valued at $25.37 in 1910 (Scott), $45.33 in 1925, $78.71 in 1930, $107.93 in 1935. It jumped to $240.65 in 1940, $306.25 in 1945, $383.45 in 1950, and $397.25 in 1955. It then broke the $500 barrier in 1960 with $527.70 and in 1965 hit $752.85. Then the real action began: in 1970 the set hit $1,834.25, and in 1975 the Scott catalog showed $3,513.25.

In just the last 10 years, the Columbian set has risen a remarkable 400 percent. Collectors and investors alike compete for it, it is likely to bring $5,000 sooner than later. In plate blocks and sheets, Columbians prove to be an even more spectacular story. A full sheet of 50 stamps of the $1.00 value was sold for $28,000, with active bidding, at the recent Siegel "Rarities" auction. At individual catalog value, the stamps would have been worth $17,500.

A further review of our Performance Table indicates that the 1847 First Issues depicting Franklin and Washington, respectively, on the 5¢ and 10¢ stamps are undervalued. While the Columbians are up 8,568 percent since 1925, and the Trans-Mississippi and Louisiana Purchase sets show about the same percentage rises, the First Issues show only a 2,164-percent increase.

Perhaps the reason is that many collectors have albums starting with the 1893 commemorative issues. The earlier "regular" issues are mostly portraits of the Founding Fathers. But popularity has finally come to these issues, after 100 years. Prices are beginning to move up—and fast. The First Issues are now listed at $4,075 in the 1976 Scott (specialized) catalog, a 38-percent jump over 1974. Further increases are likely in 1977.

Part of the value of stamps arises from people's fascination with the ancient. Holding an old, rare stamp is like holding a piece of history in your hands. Especially old covers. If you've still got grandma's love letters in your attic, you definitely have some value there. And if it's postmarked prior to 1900, it could be quite valuable, although perhaps not in the class of the greatest philatelic items in the world. The Mauritius cover of 1850 was purchased by the Weill's in 1968 for $380,000 at a Harmer auction. It last came from the Alfred Lichtenstein estate.

The single most valuable stamp in the world is the 2¢ British Guiana, an ugly, scratched blotch of purple paper with cut corners. It's the only one known to exist. Its value? Maybe $500,000…more or less. It last surfaced at a Siegel auction in 1969. An investment syndicate out of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, took it for $280,000. Its price has risen steadily ever since it was discovered by a 12-year-old schoolboy in 1873. He sold it for $1.50.

The Penny Black, a "dog" for so many years, is fast moving up in value. The world's first postage stamp, it was issued on May 6, 1840, and portrayed the Queen of England. All black, usually cut cockeyed (the perforation machine wasn't invented yet), and, in used condition, commonly marked with a thick, smudgy Maltese Cross cancellation, the stamp has become an investment winner. An average used copy was cataloged in 1975 by Scott for $35, and in 1976 for $40, a 14-percent increase. Similar desirable copies go as high as $100, especially in England. Only as recently as 1966, one could buy fine used copies for $6 to $10, or in the 1950's for $3.50. Multiples such as pairs and blocks are fetching even more exotic prices, up to $4,000 for certain variations.

DOWNSIDE RISK

The downside risk factor, on the minds of sophisticated investors considering getting into rare stamps, depends on the collectors to a great degree. While many adults have only investment motives, and will shake out to take profits, when they get nervous, it's the millions of kids and true-blue philatelists who form the all-important base. As the kids grow up, they continue to build their collections backward—reaching toward the older, rarer stamps. Thus, legitimate demand renews itself each generation.

But the older people don't sell so fast, which keeps the prices constantly moving up. Herant Mozian, principal in the 74-year-old New York City auction-dealer firm of Vahan Mozian, has commented that, "to a real philatelist, letting your stamp collection go is like letting your last teeth go."

From an investor's point of view, what it amounts to is a limited finite supply of rare stamps being chased by a growing infinite demand. The usual reaction is upward price pressure. When and if the frenzy stage hits, as it has for so many other investment forms, things could get out of hand.

AUCTION ACTION

Although not many people outside of philatelic circles know about stamp auctions and how they work, they've been around a long time. It's a big business, estimated at $200 million per year worldwide. Bernard Harmer, head of the 88-year-old prestige firm of H.R. Harmer, figures "there's an auction a day held somewhere in the world."

Harmer's does $7 million in sales through its New York City-London-Sydney operations. Robert Siegel Galleries, which runs the popular "Rarities of the World" sale each spring, does $5 million from the United States alone. The recent March auction was the first single million-dollar sale in the United States. Price realizations were phenomenal, some rarities bringing 20 percent to 100 percent higher than estimate or catalog. With only 275 lots in the sale, the average per stamp or lot was close to $4,000.

Stanley Gibbons of England also is in the bigtime auction business. Their overall sales volume, including retail, wholesale, and publishing, is more than $14 million, with auctions alone comprising $2.5 million per year. Robson Lowe, another English concern, connected with Christie, Manson, and Woods in New York, has auctions in Paris, The Hague, Basle, and Milan, doing over $3 million in business.

Handsome color-illustrated auction catalogs are mailed to thousands of eager collectors, dealers, and investors throughout the world. The key to international liquidity is universal cataloging and sequence-numbering systems. Scott is the big-name cataloger in the United States, Stanley Gibbons in England, Yvert & Teller in France, and Michel in Germany. All their catalogs are illustrated and impressively bound volumes.

Auction bidders can easily bid by mail, without examining the lots in person, guided by the sequenced catalog numbers and estimated values assigned each and every stamp issued in the world. Horse, art, tobacco, and antique car auction players don't have such luck. And when it comes to shipping out the winning bidder's merchandise, it's easier to mail an envelope of stamps than to deliver a horse. Says Abbot Lutz, U.S. agent for Stanley Gibbons: "Worldwide interest is leaping. The portability factor is important once again." When questioned about this remark, Lutz expanded. Back in 1945, many refugees aboard the Exodus had stamp albums and little else. Lutz knows—he was the cook.

The auction market is growing. Keith Harmer, of the third generation to step into the Harmer firm, sees a new trend. "In the past, there was the usual number of known buyers. Mostly dealers and a handful of avid collectors and professional agents. Now new faces are showing up and buying expensive pieces." Harmer's volume is up substantially in 1975. Their mail list increased 30 percent in the last two years, and the number of successful bidders in a general auction is up to 700 compared with 400 a few years ago. And, as Bill Roscher, the once president of Harmer's, emphatically states, "Where other artifacts have priced themselves out of the market, you can still buy stamps for under a few hundred dollars. In fact, the average price per lot in a Harmer general auction is about $125 to $150, and there's such a wide variety to choose from."

CAVEAT EMPTOR

What are the problems you can encounter with a rare stamp investment? Below is a short review of some key caveats, with accompanying solutions:

- Proper selection is imperative, as with any investment. Potential growth areas should be studied and countries or categories with overhanging supplies avoided. Beware of most new stamps; they're issued in huge quantities and are not investment-grade material.

- If you buy a "unique" stamp (one of a kind) or a very rare recently issued stamp where "only 50 are know," (etc.), you might some day discover that 5,000 exist. Investment-grade stamps have to pass the test of time or be guaranteed by the seller as to the quantity in existence.

- Avoid any source of rare stamps that does not come with impeccable personal recommendation. Never buy street-corner bargains, as they usually turn out to be duds. A good philatelic agent can do wonders for you, just as a good doctor, lawyer, and stockbroker can.

- If you're interested in a quick buck, forget it. You've got to hold rare stamps for at least a couple of years to overcome initial fees and expenses and reap maximum capital gains rewards.

- Most investment-grade stamps should be certificated or expertized by a recognized philatelic authority. Beware of local, unsophisticated dealers who will try to expertize top quality stamps and buy your rarities cheap. The major expertizing services are located in New York, London, Paris, and Berlin. Your personal agent can handle this for you, without a service charge. And if it's necessary to get your money back, it's imperative that your purchase came from a reliable source. Generally speaking, local dealers are not investment-oriented, but are geared to serve collectors.

- Values can go down as well as up, although a 50-year track record proves "up" is a better bet. It's interesting to note that of approximately 25,000 price changes in the 1975 Scott catalog for the United States, more than 24,500 were upward changes.

- Stamps do not earn interest. They grow in value, but they don't throw off dividend checks. But, there are no records to file every year. Appreciation is based on capital gains.

- Another problem is security. That's why most collectors and investors keep their philatelic endeavors quiet. Bank vaults are an excellent storage place, inexpensive and safe. Remember, millions of dollars of rare stamps can fit into the average-sized safe deposit box. Bank vaults also take care of potential humidity dangers; rare stamps should be kept at relatively stable temperature and humidity.

- Rare stamps, like other valuable assets you respect, should not be left lying around the house. If someone in your family uses one of your rare stamps to mail a letter, you're out of luck.

TULIPMANIA AGAIN

In 1634, investing in tulips was the hottest game in Holland. Everybody was making money. Rare tulips were traded on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange. And in 1636 tulipmania even spread to France and the London Exchange. Eventually people stopped buying rare tulips and the bubble burst. Bankruptcies were widespread, and the ensuing chaos lasted for years.

Will history repeat itself with rare stamps? Non-philatelists have been getting into stamps purely for speculation and investment, driving prices up. The wild speculative phase of the cycle hasn't hit yet, but those close to the situation can almost smell it coming. Nevertheless, there are major differences between rare stamps and rare tulips.

Stamps have a multimillion collector base—growing rapidly. Tulips also grow, but one never knows exactly how many there are, or who's growing them, or where. With rare stamps, government has the monopoly and certifies the quantity printed—thus the finite supply tied to the infinite demand. And, although pretty to look at, tulips are certainly not a permanent asset that one can store in a bank vault and auction off five years hence or pass on to family members. Stamps, on the other hand, have passed the test of time, proving their investment mettle over a 100-year period.

Myron Kaller is a philatelic agent and consultant. He personally owns many of the world's greatest rarities. His book, charting stamp price trends (the first of its kind) will be published in the fall of 1976.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Stamps."

Show Comments (0)