Alex Berenson Is a Little Too Eager to Prove That Weed Makes People Crazy

The relationship between cannabis consumption and psychiatric diagnoses is more subtle and ambiguous than the anti-pot polemicist implies.

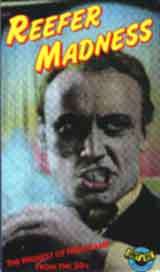

Alex Berenson complains that he has been "mocked as a modern-day believer in 'Reefer Madness,' the notorious 1936 movie that portrays young people descending into insanity and violence after smoking marijuana." Yet the former New York Times reporter decided to call his new book about the mental health hazards of cannabis Tell Your Children, the original title of that camp classic.

Although I have not read Berenson's book yet, I am sure it surpasses the scientific rigor of a movie that portrays madness and murder as routine consequences of cannabis consumption. But judging from Berenson's recent New York Times op-ed piece summarizing his findings, the book shares with its namesake a tendency to favor scaremongering over a judicious weighing of the evidence.

Keen to show he is no crackpot, Berenson quotes The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids, a 2017 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM): "Cannabis use is likely to increase the risk of schizophrenia and other psychoses; the higher the use, the greater the risk." While Berenson describes that sentence as a "conclusion" of the report, it actually appears in the "highlights" section at the beginning of Chapter 12, and it overstates what NASEM's research review found. NASEM's official conclusion on this point is decidedly more ambiguous: "There is substantial evidence of a statistical association between cannabis use and the development of schizophrenia or other psychoses, with the highest risk among the most frequent users."

Contrary to the impression left by Berenson, the nature of that relationship remains unclear. "There are a number of proposed explanations for why the comorbidity of substance abuse and mental health disorders exists," the report notes. One possibility, favored by Berenson, is that "substance use may be a potential risk factor for developing mental health disorders." Another hypothesis is that "mental illness may be a potential risk factor for developing a substance abuse disorder." A third explanation is that "an overlap in predisposing risk factors (e.g., genetic vulnerability, environment) may contribute to the development of both substance abuse and a mental health disorder."

One, two, or all three of these hypotheses might be true to some extent. As NASEM puts it, "the relationship between cannabis use and cannabis use disorder, and psychoses may be multidirectional and complex." The report also notes that "in certain societies, the incidence of schizophrenia has remained stable over the past 50 years despite the introduction of cannabis into those settings"—a puzzling fact if you believe that marijuana use makes schizophrenia more common.

To reinforce his interpretation of the relationship between cannabis consumption and mental health disorders, Berenson cites data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), which he says "show that rates of serious mental illness are rising nationally, with the sharpest increase among people 18 to 25, who are also the most likely to use cannabis." The most common "mental illnesses" identified by NSDUH are anxiety and depressive disorders. An NSDUH document to which Berenson links, for instance, shows a 27 percent increase in the rate of "major depressive episodes" among 18-to-25-year-olds between 2015 and 2017. But according to the NASEM report, "cannabis use does not appear to increase the likelihood of developing depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder."

Berenson thinks marijuana's dangers make "decriminalizing possession" a better policy than legalization. "I am not a prohibitionist," he writes. "I don't believe we should jail people for possessing marijuana." But reducing penalties for marijuana use while maintaining a ban on commercial production and distribution is morally incoherent: If it should not be a crime to use marijuana, why should it be a crime to help people use marijuana?

The "decriminalization" favored by Berenson is also contrary to the interests of consumers. Whatever the hazards of marijuana use, prohibition surely does not reduce them or make them easier to deal with. To the contrary, prohibition tends to make drug use more dangerous and unpredictable, while a legal market featuring a wide variety of products that are tested for potency and come in labeled doses, accompanied by open discussion of precautions aimed at minimizing unpleasant effects (such as "start low, go slow" for edibles), tends to reduce risk.

The case for repealing marijuana prohibition does not depend on demonstrating that "the drug is safe," which Berenson takes to be the message of "legalization advocates." Rather, the question is how a free society should deal with potentially dangerous activities that people enjoy, taking into account not only the claims of individual liberty but also the ways in which prohibition aggravates the harms it aims to prevent.

Show Comments (19)