As Opioid Prescriptions Fall, Opioid Deaths Rise

The latest data underline the folly of tackling the "opioid crisis" by restricting access to pain pills.

The decline in opioid prescriptions that began in 2011 accelerated last year, according to the latest data. Meanwhile, opioid-related deaths continue to rise. The opposing trends show the folly of tackling the "opioid crisis" by restricting access to pain medication.

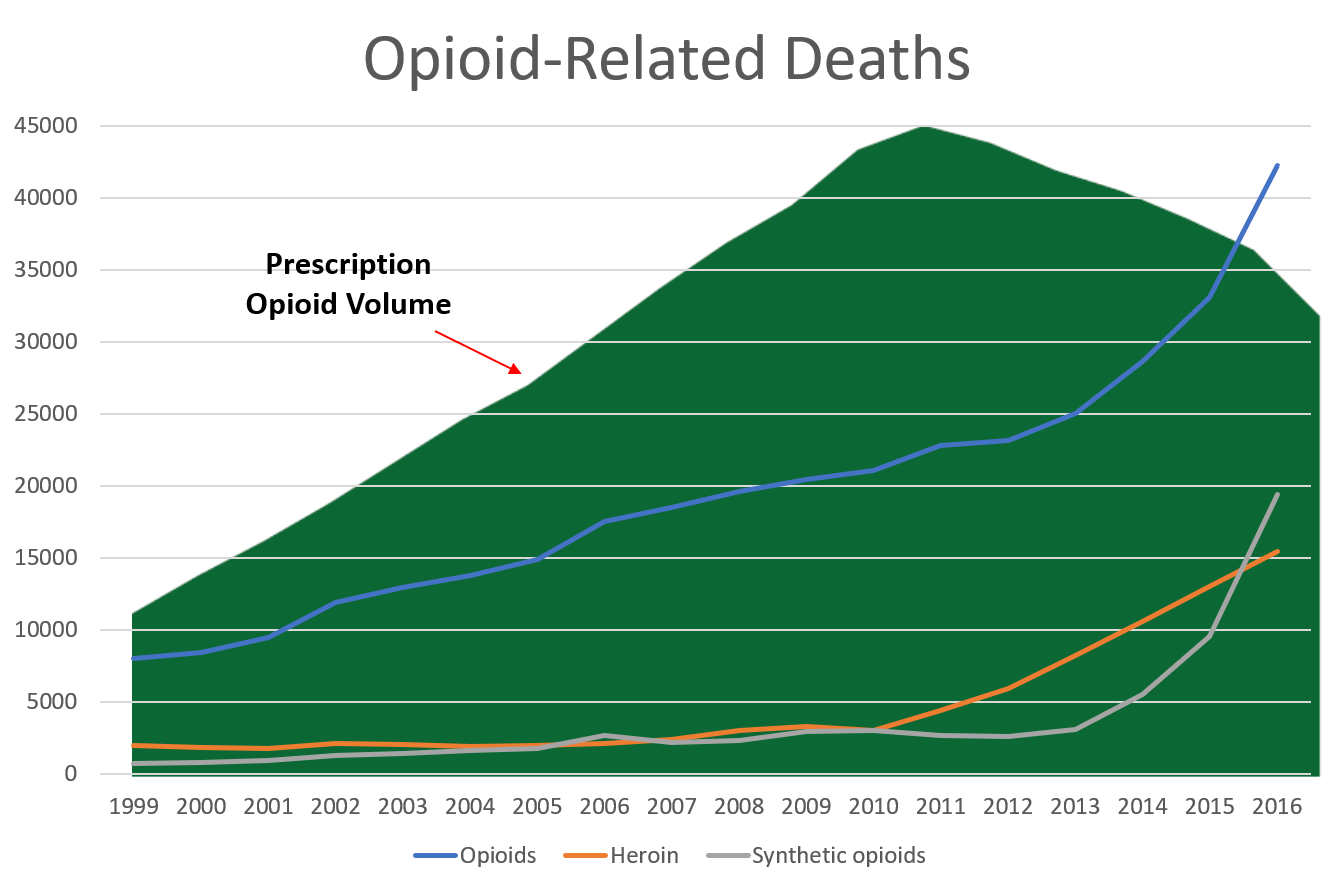

A report published yesterday by the health care consulting firm IQVIA shows that the total volume of opioids prescribed in the United States, indicated by the green area below, fell by 29 percent between 2011 and 2017, from 240 billion to 171 billion morphine milligram equivalents. Last year's 12 percent drop was the largest ever recorded. The number of opioid prescriptions and the number of patients receiving opioids for the first time are also declining. The report notes that "decreases in prescription opioid volume have been driven by changes in clinical usage, which have been influenced by regulatory and reimbursement policies and legislation that have been increasingly restricting prescription opioid use since 2012."

But as you can see in the graph, the total number of opioid-related deaths counted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, indicated by the blue line, is not falling along with opioid prescriptions. To the contrary, it has risen sharply in recent years, driven by dramatic increases in deaths involving heroin (orange) and illicit fentanyl (the main component of "other synthetic opioids," the category represented by the gray line). The CDC has not released final data for 2017 yet, but more increases are expected.

The crackdown on pain pills not only has not reversed the upward trend in opioid-related deaths. It is contributing to it by driving nonmedical users into the black market, where the drugs are more dangerous because their purity and potency are inconsistent and unpredictable. The vast majority of opioid-related deaths now involve illegally produced drugs: heroin, fentanyl, and its analogs. The crackdown is also hurting chronic pain patients, including people who have functioned well on opioids for years but now find it difficult or impossible to obtain the medication they need to maintain a decent quality of life.

Since the current strategy is manifestly not working, drug warriors are, as usual, redoubling their efforts. The Drug Enforcement Administration, which sets annual quotas for opioid production, reduced the limit by 25 percent in 2017 and 20 percent this year. Now the DEA plans to squeeze the supply some more.

The Washington Post reports that the agency will decide how much pain medication should be available based on the "legitimate medical needs of patients" rather than the number of pills manufacturers expect to sell. But the number of pills manufacturers expect to sell is based on the number doctors are expected to prescribe, which is in turn based on their judgment of patients' legitimate medical needs. The DEA is substituting its judgment for theirs, without even bothering to conduct an exam or take a medical history. For a doctor, that would be malpractice. For a drug warrior, it is all in a day's work.

Show Comments (77)