'Sensitivity Readers' Are the New Thought Police, And They Threaten More Than Novelists

Nobody calls himself a censor anymore in the 21st century. We've got better words for it.

Welcome to the 21st century and "sensitivity readers," people hired by writers and publishers, especially of young-adult titles, to vet manuscripts to make sure things are, well, politically correct, "authentic," and, especially, inoffensive.

Like fact checkers or copy editors, sensitivity readers can provide a quality-control backstop to avoid embarrassing mistakes, but they specialize in the more fraught and subjective realm of guarding against potentially offensive portrayals of minority groups, in everything from picture books to science fiction and fantasy novels.

As The New York Times reports, sensitivity readers don't just weigh in on matters of historical accuracy. They also have a say in speculative fiction, sometimes even after a book has been published. That's what happened to Keira Drake, when advanced copies of her fantasy novel The Continent received a hostile response from readers.

Online reviews poured in, and they were brutal. Readers pounced on what they saw as racially charged language in the descriptions of the warring tribes and blasted it as "racist trash," "retrograde" and "offensive." Ms. Drake and her publisher, Harlequin Teen, apologized and delayed the book's publication.

In the year since, "The Continent" has changed drastically. Harlequin hired two sensitivity readers, who vetted the narrative for harmful stereotypes and suggested changes. Ms. Drake spent six months rewriting the book, discarding descriptions like her characterization of one tribe as having reddish-brown skin and painted faces. The new version is due out in March.

What's the harm, exactly? As the Times points out, sensitivity readers, despite the Orwellian or Huxleyan euphemism, are really about quality control, right?

"It's a craft issue; it's not about censorship," said Dhonielle Clayton, a former librarian and writer who has evaluated more than 30 children's books as a sensitivity reader this year. "We have a lot of people writing cross-culturally, and a lot of people have done it poorly and done damage."

That's one way of looking at it. But in a culture that rightly champions free expression, assimilation, class-race-and-gender mixing, and empathy, it's a practice that threatens to choke off work. There's no good reason that a small group of experts should be able to claim that it alone can validate a manuscript (and, one presumes, movies and other art forms) as authentic and real for potential protesters who will claim that this or that book must be pulled from shelves, heavily rewritten, or just not published at all. Publishers are free to print (or not) whatever they want, but this is a barely disguised version of thought control that would redact much of children's literature. Author Francine Prose, a progressive novelist if ever there was one, writes in The New York Review of Books of the essential mistake undergirding reliance on sensitivity readers and identity politics when it comes to literature.

We know that many classic novels and children's books have included hideously racist images and passages that make us cringe. One hesitates to put such books into the hands of young readers without cautionary guidance. Not long ago, my granddaughter found, in the attic, a deck of tiny picture cards illustrating the adventures of the Spanish-language version of Little Black Sambo. It seemed helpful, rather than destructive, to be able to explain to her that once it was considered okay to picture black people that way. At six, she was old enough to be appalled, which seemed helpful, educational, surely: the germ of an idea about history and the world.

The young, we know, are impressionable, though one might ask if we aren't giving kids and their families too little credit for being able to sift truth from falsehood, right from wrong. Do we seriously think that books have that much power in shaping character—that Donald Trump, Stephen Bannon, and Richard Spencer are the way they are because their childhood readings lists weren't properly vetted?

Let's leave aside the not-insignificant fact that major publishers are not trying to crank YA or literary versions of The Turner Diaries. They are trying to engage readers who are seeking to either experience something different than what they know or to see their experience reflected back at them. These two aims aren't mutually exclusive by any means, but something the right-wing and left-wing cultural commissars have long believed in what scholar Joli Jensen calls "instrumental culture." In this view, books and other forms of art are essentially like medicine that's injected into people and forces them to think or behave a certain way; bad books (and movies, music, TV shows, etc.) create bad citizens. But that's the wrong way to think about the art we produce and consume, says Jensen, who makes the argument at length in her excellent 2002 study Is Art Good for Us?:

There's an assumption that art is an instrument like medicine or a toxin that can be injected into us and transform us. But there's very little evidence of a direct effect, and we all participate in creating the meaning of a particular piece of work. We should always be considerate about how we choose to tell stories and the stories we choose to tell. That's an ongoing cultural conversation, but I mistrust attempts to control that conversation by excluding a priori categories of stories or by assuming that the stories we are telling are harming us.

Since Is Art Good for Us? was published after a decade of bipartisan attempts to censor rap music and video games, the movement to constrain what is considered acceptable discourse has grown exponentially.

The entire case against cultural appropriation, for example, is based on mistaken beliefs that only certain people can legitimately represent certain points of view even when it comes to cuisine, a traditional example of mongrelization gone beautifully mad (all cooking is fusion, as any pasta-and-tomato-eating Italian will tell you). If we cannot get outside of ourselves through the act of producing and consuming culture that transcends our genetics and sociological milieu, what a degraded experience we will be doomed to lead. In the current moment, sensitivity readers reflect not a good-faith effort to avoid stupid mistakes and offense but a thought-police goon squad enforcing strict parameters on what we can think and say. They are part of the apparatus that is producing more members of the fragile generation, the term that Lenore Skenazy and Jonathan Haidt have coined to describe a world in which children especially are seen as incapable of processing even the smallest problem without suffering long-term, major damage.

There's something else to think about, too, which is that sensitivity readers won't save authors and publishers from hostility. Protesters hell-bent on being offended will always find a grievance, a megaphone, and a Quisling.

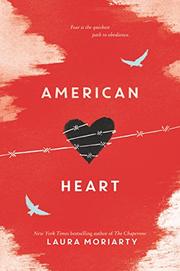

Consider the case of Laura Moriarity, whose forthcoming novel American Heart "unfolds in a dystopian America where Muslims are rounded up and sent to detainment camps." The narrator is a white girl and even though the publisher and Moriarity worked with sensitivity readers and the book received a coveted and rare starred review from Kirkus, an intense, immediate online uproar about the book's basic premise erupted. The original review, written by a Muslim women, called it "suspenseful, thought-provoking and touching." An online mob, which presumably had not yet read the unpublished book, saw it differently, as an intolerable "white savior narrative" and worse.

Critics of the book, who saw the story as offensive and dehumanizing to Muslims, bombarded Kirkus with complaints, demanding the review be retracted. Kirkus took down the review and replaced it with a contrite statement from its editor in chief, Claiborne Smith, who noted that the review, which was written by a Muslim woman, was being re-evaluated. When a revised version of the review was posted, it was more critical, and had been stripped of its star.

"I do wonder, in this environment, what books aren't being released," Moriarity tells the Times.

Related video from 2014: The long war to ban comic books, video games, and other kids' culture.

Show Comments (132)