The Myth of the Playground Pusher

In Tennessee and around the country, "drug-free school zones" are little more than excuses for harsher drug sentencing.

On July 9, 2008, officers of the Columbia, Tennessee, police department arrested Michael Goodrum and charged him with possession of crack cocaine with intent to distribute in a drug-free school zone.

Sounds bad, right? Surely the kind of monster who sells crack in a school yard should be put away for a long time. Lawmakers certainly think so: All 50 states and the District of Columbia have laws on the books that provide for harsh sentences for people who buy or sell drugs near schools. In Tennessee, it's considered such a serious crime under the state's Drug-Free School Zone Act of 1995 that Goodrum's charge was automatically upgraded to a Class A felony—the same category as murder.

But Michael Goodrum was not peddling dope to kids on a playground. He wasn't on school property, and school wasn't in session. In fact, he wasn't within sight of a school.

According to court testimony by the police who arrested him, the 40-year-old was sitting in a private residence at 10:30 p.m. when officers swept into the living room with a narcotics search warrant. Goodrum was ordered to the floor, and when an officer picked him up, the cop found a small bag of crack cocaine underneath him.

Goodrum says he was only visiting the house. He had never been convicted of a felony before.

Normally, he would have been facing a stiff eight years in prison for possession with intent to sell of 1.7 grams of crack cocaine. (That's about the same weight as two blueberries.) But the room he was in happened to fall within 572 feet of a park and 872 feet of a school—roughly two blocks away from either, but still well within the 1,000-foot drug-free radius created under Tennessee law.

After a four-year odyssey involving a hung jury and a retrial, Goodrum was convicted and sentenced to 15 years without the possibility of an early release. Had he been convicted of second-degree murder, he might have ended up serving less time in prison. That crime carries a minimum 15-year sentence but includes a possibility for release within 13.

Goodrum's case isn't unusual. Drug-free school zone laws are rarely if ever used to prosecute sales of drugs to minors. Such cases are largely a figment of our popular imagination—a lingering hangover from the drug war hysteria of the 1980s. Yet state legislatures have made the designated zones both larger and more numerous, to the point where they can blanket whole towns. In the process, they have turned minor drug offenses into lengthy prison sentences almost anywhere they occur.

In some cases, police have set up controlled drug buys inside school zones to secure harsher sentences. That gives prosecutors immense leverage to squeeze plea deals out of defendants with the threat of long mandatory minimum sentences.

In recent years, this approach has begun to trouble some state lawmakers, and even some prosecutors are growing uncomfortable with the enormous power—and in some cases, the obligation—they have been handed to lock away minor drug offenders.

Nashville District Attorney Glenn Funk ran for office in 2014 on a platform that included not prosecuting school zone violations except in cases that actually involve children. He says almost every single drug case referred to his office falls within a drug-free zone.

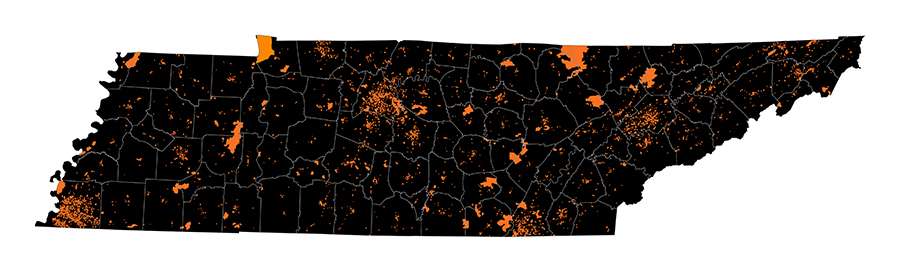

He's right. Data obtained from the Tennessee government show there are 8,544 separate drug-free school zones covering roughly 5.5 percent of the state's total land area. Within cities, however, the figures are much higher. More than 27 percent in Nashville and more than 38 percent in Memphis are covered by such zones. They apply day and night, whether or not children are present, and it's often impossible to know you're in one.

For a drug offender charged with possession of under half a gram of cocaine with intent to distribute, a few hundred feet can mean the difference between probation vs. eight years of hard time behind bars.

"In places like Nashville, almost the entire city is a drug-free zone," Funk says. "Every church has day care, and they are a part of drug-free zones. Also, public parks and seven or eight other places are included in this classification. And almost everybody who has driven a car has driven through a school zone. What we had essentially done, unwittingly, was increased drug penalties to equal murder penalties without having any real basis for protecting kids while they're in school."

The Rise of the Drug-Free Zone

Goodrum is one of 436 inmates currently serving time in Tennessee state prisons for possessing or selling drugs in a drug-free zone. The oldest of those inmates, Harry Watts, was 74 years old at the time of his sentencing. It was his first felony conviction. The youngest, Sammy Russell, was 16 when he received eight years in an adult prison for having half a gram of cocaine, or less than a packet of sugar, on him. It was his first felony conviction as well.

For a drug offender charged with possession of under half a gram of cocaine with intent to distribute, a few hundred feet can mean the difference between probation or release within three years, on one hand, vs. eight years of hard time behind bars without any hope of parole, on the other.

Tennessee's drug-free school zone laws are among the harshest in the country, but the state is far from an outlier. Statutes that increase sentences for drug crimes that occur near schools or other places where children congregate—parks, rec centers, libraries, day cares—exist in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Congress created the first drug-free zone law in 1970 as part of the federal Comprehensive Drug Abuse, Prevention and Control Act. At the time, supporters argued that the laws deterred drug sales to children and reduced other criminal activity associated with drugs in areas around schools.

"Those who have a drug habit find it necessary to steal, to commit crimes, in order to feed their habit," President Richard Nixon said in a signing statement. "We found also, and all Americans are aware of this, that drugs are alarmingly on the increase in use among our young people. They are destroying the lives of hundreds of thousands of young people all over America, not just of college age or young people in their 20s, but the great tragedy: The uses start even in junior high school, or even in the late grades."

The law was amended in 1986, near the height of the '80s-era drug panic, to double the maximum sentence for drug distribution or manufacturing within 1,000 feet of a school, college, or playground, and to add areas within 100 feet of swimming pools, video arcades, or youth centers.

States followed suit. Throughout the 1980s and '90s, drug-free school zones became ubiquitous throughout the country. In the 1990s, some states expanded their zones to include public housing, shopping malls, parking lots, and amusement parks, as well as expanding the types of offenses that would be covered. Indiana expanded its drug-free zones to include public housing complexes and "youth program centers." Utah brought in movie theaters, parking lots, arcades, and malls. Washington state included bus stops.

Pennsylvania was the last state to enact a basic drug-free school zone law, in 1997. But a few states have expanded theirs as recently as 2015, despite widespread support for other criminal justice reforms that reduce, rather than ratchet up, penalties for nonviolent crimes. In 2011, Arkansas changed its law to allow simple drug possession offenses that occur in drug-free zones to be eligible for the state's mandatory 10-year sentencing enhancement. In 2012, Hawaii amended its law to include public housing complexes. In 2015, Texas enacted legislation that allows for opioids to be included in the list of substances eligible for a drug-free zone sentencing enhancement.

Alabama has the widest drug-free zones in the country, extending three miles from schools, colleges, and housing complexes. Drug offenses inside those areas carry a five-year enhanced sentence. In practice, this means that 38,267 square miles of Alabama—73 percent of the state—are within a -drug-free zone. Cities with a higher concentration of schools and public housing projects are worse. Ninety-four percent of Montgomery falls within a drug-free zone.

Prosecutors and law-and-order legislators have fiercely opposed changes to these laws. When the Connecticut legislature considered shrinking the size of its drug-free zones in 2012 from 1,500 feet—a distance of more than three football fields—to 200 feet, one outraged lawmaker testified that he was "appalled as to why anyone would support a bill that puts our children at greater risk by easing restriction on drug dealers."

"Many children walk this distance every day to and from school, and it is our job to ensure there are laws in place which adequately protect them," Republican state Rep. Prasad Srinivasan declared. "As drugs get closer to our schools, other forms of crime and violence will certainly follow."

Phantom Pushers

The fearsome image that spurred these laws and keeps them on the books—a shifty drug dealer handing a child a bag of drugs through a chain-link fence—is little more than a phantom.

Funk, the Nashville district attorney, says that over the last three years he's dealt with only three drug cases that involved the actual endangerment of a child. One happened when a suspect fleeing the police ran through a middle school's grounds, sending the school into a lockdown.

In the early 2000s, former Massachusetts Assistant Attorney General William Brownsberger conducted a review of drug cases in three Massachusetts cities. He found that 80 percent of them occurred in drug-free school zones, but almost none of them involved sales to minors.

"In all of those cases that we looked at, in that entire set of about 450 files from two different district attorney's offices over the course of a year, there was exactly one case of drug dealing to a minor," says Brownsberger, now a Massachusetts state senator. "That happened in an apartment late at night, and it just happened to be near a school."

In all the years since, he's still never come across a case of the dreaded playground pusher in action.

"I've been a practitioner in the area for 10 years and a legislator for another 10, and I've never seen that case," he says. "The only cases that I'm aware of involving dealing drugs on or in a school are always kids selling to other kids. Usually in those cases, you don't want them getting a two-year mandatory minimum. It's just totally inappropriate. The whole school zone concept is bankrupt and should be repealed entirely."

States created drug-free school zones thinking that the threat of draconian prison sentences would keep dealers away from schools. But the very size of these zones undercuts that premise. If a whole city is a drug-free zone, then the designation has no targeted deterrent effect. In practice, it exists to put more people in prison for longer periods of time, not to keep children safe.

"Drug-free school zone laws show how good intentions can go horribly wrong," says Kevin Ring, president of the advocacy group Families Against Mandatory Minimums. "Adult offenders who aren't selling drugs to or even near kids are getting hammered with long sentences. Most don't even know they are in a school zone. These laws aren't tough on crime. They're just dumb."

'We Don't Need the Police Department Setting Up Buys on School Property'

By covering wide swaths of densely populated areas in drug-free zones, states end up hitting low-level and first-time drug offenders with sentences usually reserved for violent crimes.

Tennessee's drug-free school zone laws bump up drug felonies by a level and eliminate the possibility of an early release. For example, a first-time drug offender found guilty of a Class C felony for possession with intent to distribute of less than half a gram of cocaine—which carries a maximum six-year sentence—instead receives a Class B felony with a mandatory minimum sentence of eight years.

These penalties are zealously applied. Knoxville criminal defense attorney Forrest Wallace says that one of his clients received an enhanced drug sentence for merely walking through a school zone that bisected the parking lot of his apartment complex on his way to meet the informant who had set him up. The client received a normal sentence for the sale of the cocaine, but an enhanced charge of possession with intent to distribute for passing through the school zone.

"If they can prove it's in a zone, you know they're going to charge it," Wallace says. "That's just the way it is."

Undercover cops and confidential informants sometimes go to extra lengths to get these enhanced sentences. David Raybin, a Nashville criminal defense attorney, says that police informants often purposely set up deals in school zones, a practice that has led to accusations of entrapment from defendants and rebukes from judges dismayed by the practice. "The police will frequently have people sell drugs in a school zone so they can enhance them," Raybin says.

"The only cases that I'm aware of involving dealing drugs on or in a school are always kids selling to other kids. Usually in those cases, you don't want them getting a two-year mandatory minimum. It's just totally in appropriate."

Tennessee resident Jordan Peters was 20 years old when he sold a bag of hallucinogenic mushrooms to a police informant at a gas station in 2010. Peters testified at trial that the informant had been "blowing up" his phone and asking for drugs. He said he told the informant that he needed to gas up his car before meeting her, and the informant suggested they just meet at the station.

Peters had no prior criminal history, but because the $80 drug transaction happened 587 feet from an elementary school, he received a mandatory 15 years in state prison. He will not be released until 2027.

Peters' case is not unusual. In a 2015 ruling upholding his sentence, Appellate Judge Camille McMullen noted her "increasing concern regarding enhancement of convictions under the Act."

"I simply do not believe that the Tennessee legislature intended the scope of the Act to include drugs brought into the protected school zone by law enforcement's own design," she wrote. "This concept of luring, which commonly takes the form of an undercover sting operation, is inconsistent" with the law's goal of reducing illegal drug activity around schools. (In the end, however, McMullen "reluctantly" concurred with her two fellow judges that, based on precedent, Peters' case did not amount to entrapment.)

In another case, a judge warned that drug stings on school grounds could create an unsafe environment for students. In 2001, police officers from Davidson County's Metro Drug Task Force testified at the trial of defendant Baudelio Nieto that they had driven Nieto to an elementary school parking lot to discuss a cocaine deal for the expressed purpose of securing an enhanced sentence against him. The tactics bothered Judge John Aaron Holt. "All the problems we are having with our schools, we don't need the Police Department setting up [drug] buys on school property," he said, according to The Tennessean. "This is not a good thing to be doing."

Nieto's lawyer, Mario Ramos, says he has worked on three or four cases where police set up drug transactions in drug-free zones. "Literally every time there was a drug buy, they were trying to figure out how to get near a school," Ramos says. "It led to enhanced punishment, and of course the enhanced punishment gave them a greater negotiating arm."

But such planning is largely unnecessary because of the ubiquity of school zones and the lack of viable defenses for drug offenders who stumble into them. Tennessee's drug-free zone laws do not include what's known as a mens rea—Latin for "guilty mind"—requirement. That means defendants are just as culpable if they had no idea they were in a drug-free zone, which in the state extend roughly three city blocks as the crow flies from designated areas.

The law applies even if one is driving down a closed-access highway that happens to pass through a school zone. Take the case of Danny Santarone: In 2011, a FedEx employee flagged a suspicious package (which turned out to be full of prescription opioids) addressed to Santarone. Police watched him arrive and pick up the package, but they waited to initiate a traffic stop until he was down the road, inside a school zone.

Santarone later received enhanced sentences for possession of oxycodone, cocaine, and heroin with intent to distribute. A Tennessee appeals court denied his appeal in 2015, ruling that "the state is not required to prove that the defendant knew that he was committing an offense within 1,000 feet of a school, nor even that school was in session at the time of the offense."

Locking Up Minorities

Like many U.S. drug laws, drug-free school zone statutes have a disparate impact in low-income and minority neighborhoods. This can be partially explained by the fact that cities, which have a higher percentage of minority populations than rural areas do, often have overlapping drug-free zones, since schools, parks, and other youth services tend to be located near low-income housing. Eleven states explicitly include public housing complexes in their drug-free zones.

Sentencing data from Tennessee show minorities are indeed disproportionately represented in school zone sentences relative to their share of the population. Tennessee is 17.1 percent black, but blacks make up 69 percent of all drug-free school zone offenders currently serving time in the state.

The disparities continue at the county level. For example, Knox County, Tennessee, is 6.8 percent black, but blacks make up 27.6 percent of all school zone sentences.

"Once you start looking at these things, you'll notice that in Knox County there are certain areas of town where there's a higher population density and a higher density of restricted zones," Wallace says. "Coincidentally, a lot of those places happen to be in a poorer section of town. Knoxville is a historically segregated city, so the majority of the African-American population lives in East Knoxville. There's a huge concentration of restricted zones in East Knoxville. I always joke that you can't swing a cat without it landing in a drug-free school zone."

He's right, too: 39 percent of the city is covered by a drug-free zone, but in poorer East Knoxville that figure is 58 percent.

State Senate Minority Leader Lee Harris (D–Memphis), who has been working to reform school zone laws, describes a huge gulf between how the laws affect rural areas and major cities like Memphis.

"You end up creating all these different zones, and it swallows the entire city," Harris says. "You compare that to what a rural county looks like. The other 91 rural counties in the state, the vast majority of their space is not in a drug-free school zone. I have to ask those who are concerned about justice and fairness, why should drug dealers who live in cities get 15 years while drug dealers who do the same crime get 29 months because they live in a rural area? At the end of the day, drug-free zones just penalize people for living in cities. I mean, you can't get 10 years for some homicides."

But this is not solely an urban issue. More than 13 percent of all Tennessee inmates serving drug-free zone enhancement sentences are from rural Maury County, population 28,000. Although only 4 percent of Maury County's total area is covered by drug-free zones, 21 percent of the area within city limits in the county is covered by a drug-free zone. Of the 58 inmates from the county who are serving these sentences, 45 are black, even though African Americans make up only 0.43 percent of all Maury County residents.

A disproportionate number of drug-free zone inmates come from rural Sullivan County as well. Although the county accounts for roughly 2.5 percent of the state's population, over 22 percent of all drug-free zone inmates were convicted here. More than half of these inmates are black, compared with only 2.6 percent of the county's population. Like Maury County, the total area covered by drug-free zones in the county is low (8.6 percent). However, 28 percent of cities within Sullivan County are covered by these zones.

Minorities also receive longer drug sentences than whites for school zone violations statewide. Sentencing data show that white defendants receive eight-year sentences on average, while blacks and Hispanics receive 11.6 years and 15 years on average, respectively. Out of the top 20 longest drug sentences for school zone violations, only two of the defendants were white.

This pattern isn't limited to Tennessee. A 2007 study by the New Jersey Commission to Review Criminal Sentencing found that "nearly every offender (96 percent) convicted and incarcerated for a drug-free zone offense in New Jersey is either Black or Hispanic." According to the report, overlapping drug-free zones had "a devastatingly disproportionate impact on New Jersey's minority community." At one point, roughly 50 percent of both Newark and Jersey City were covered by drug-free zones.

A study in Connecticut showed similar results. "Two of our big cities, Bridgeport and Hartford, are completely covered by these zones," says David McGuire, executive director of the state's American Civil Liberties Union chapter. "In New Haven, the only place that's not included is the Yale golf course."

A 2010 report commissioned by the Illinois General Assembly also concluded that the state's drug-free zone law had a disproportionate impact on minority communities. It found that nearly 90 percent of arrests for drug-free zone violations in Illinois involved nonwhite arrestees. In Florida, a 2011 report published by the state Senate's Committee on Criminal Justice found that black offenders made up 55 percent of admissions to prison for all drug offenses in fiscal year 2009, but they made up 88 percent of those admitted to prison for a drug-free zone conviction that same year.

The Prosecutor's Toolkit

When Memphis resident Rodgerick Griffin Jr. was arrested for possession with intent to distribute a sugar packet's worth of crack cocaine in 2009, he was originally charged with a Class B felony. But because the offense occurred three blocks from a school, it was elevated to a Class A felony. Instead of a maximum eight-year sentence with parole eligibility in under three, Griffin faced a minimum of 15 years in prison with no possibility of an early release. He would have faced less time in prison under Tennessee sentencing guidelines if he had been convicted of rape or aggravated robbery.

The outsized sentencing mandates in drug-free school zone laws give prosecutors incredible leverage. Rational defendants are more likely to take a plea deal, even if they believe they are innocent, when the punishment from losing at trial is much more severe than the deal being offered by the prosecutor.

"With the enhancement, what was happening was somebody might have a couple grams of cocaine, and they'd go to court, hoping to get probation for simple possession," Funk explains. "Their lawyer would then tell them it's a school zone case, and they're looking at 15 to 25 years in prison. The state offers them eight years to serve at 30 percent, or a 10-year probationary period or something. If the client persists, the lawyer has to say, 'Do you feel lucky? Because if you go to trial and lose, you won't be home for the next couple of decades.'"

Available sentencing data include only defendants who went to trial, not cases where prosecutors dropped school zone charges in exchange for a guilty plea. So there are almost certainly many more Tennessee inmates serving drug sentences longer than those they would have normally received because of deals struck with prosecutors under threat of school zone sentence enhancements.

"There's an astronomical amount of people who were threatened with school zone charges," Raybin says. "I can tell you, anecdotally, it goes on all the time."

Rodgerick Griffin ultimately pleaded guilty, caving to the threat of decades behind bars, and received eight years in prison with no possibility of an early release.

"His son will be 19, and Terrance has basically missed every milestone—going to kindergarten, fifth-grade graduation, high school graduation, college move-in day. He's missed so much."

Such deals are the rule, not the exception, in the criminal justice system. More than 97 percent of all federal cases end in plea deals, leaving only a tiny percentage to be disposed of at trial. In some states, an actual trial by a jury of one's peers, as guaranteed by the Constitution, is an endangered species.

McGuire notes that Connecticut's geographic area courts, which handle all misdemeanor and most felony cases in the state, had a total of 74,503 cases in 2016.

"How many of those cases do you think were disposed of at trial?" he asks, pausing for effect.

"103."

'It's Tearing Families Apart'

For a measure meant to protect children, drug-free zones have been awfully destructive for families.

Nashville resident Joi Davis' husband, Terrance, has been incarcerated since 2003 on drug-free school zone charges. Undercover police bought more than 20 grams of cocaine from him one night inside his apartment.

If he'd lived in a unit on the other side of the gated complex, he would have faced 12 years in prison for the drug charges, with the possibility of parole within four, and would likely be a free man today. But his actual residence fell just within a school zone, so he ended up taking a plea deal for 22 years. He had prior drug offenses, but no violent criminal history. It was, in fact, a somewhat generous deal from the prosecutors' perspective, considering the several other charges and maximum sentences they could have pursued against him.

"Boom, there he goes, a decade and a half of his life already gone, all because of a couple hundred feet," Davis, an employee at a charter school, says in a phone interview. "I know for a fact there's people who have committed crimes like second-degree murder and rape, and they have went home, whereas Terrance is sitting there twiddling his thumbs and patiently waiting."

"His son will be 19, and Terrance has basically missed every milestone—going to kindergarten, fifth-grade graduation, high school graduation, college move-in day," the 39-year-old adds. "He's missed so much."

Thanks to a judge's ruling, her husband will be eligible for parole in under a year, after he finishes the mandatory 15-year portion of his sentence. Davis says they have a five-year plan for after he gets out: a truck driving license, maybe their own business, a little log cabin somewhere nice.

Until his release, Davis works and counts the days. Some days she sends out 30 to 40 emails to state lawmakers about the injustice of Tennessee's school zone laws. She talks about turning her one-woman advocacy blitz into a nonprofit organization.

"It's not just affecting my family," she says. "There's plenty of other families out there. Some lawmakers really want change, but the ones voting against it need to see it's wasteful for taxpayers, it's tearing families apart, and it's so unnecessary."

Reform at Last?

Many states, both liberal and conservative, are now reconsidering their drug-free school zone laws, but lawmakers are reluctant to roll back legislation that's supposed to protect children.

In 2008, the Indiana legislature was considering a bill to expand its drug-free zones to include churches and bus stops. A group of freshmen from DePauw University, taking a class on public policy from former political science professor Kelsey Kauffman, testified at a committee hearing and brought along a map they had created showing what the result would look like.

The drug-free zones would have swallowed nearly everything in Indianapolis except the airport. As it stood, state laws already created what the students called overlapping "superzones."

The classmates were the only ones to testify against the proposal. After they revealed the map, the hearing was "absolute pandemonium for the next hour and a half," Kauffman says. The bill passed through the committee by one vote, but it died in the state Senate.

Groups of freshmen from Kauffman's classes continued to bring their maps to the legislature over the next several years, and in 2014, then–Gov. Mike Pence signed a law, over the objections of the state prosecutor association, shrinking Indiana's drug-free zones from 1,000 to 500 feet, reducing the sentences for school zone violations, and removing public housing complexes and youth centers from the designation.

Utah lawmakers passed a bill in 2015 that dramatically altered its drug-free zones, reducing their size from 1,000 feet to 100 feet and limiting their application to between 6 a.m. and 10 p.m. around schools, and only during business hours around other locations. Prior to 2015, the zones covered 10 percent of the entire state and made any drug offense except for possession a first degree felony if it occurred near a school, public park, amusement park, arcade, recreation center, church, shopping mall, sports facility, movie theater, playhouse, or parking lot.

Massachusetts lawmakers passed a bill in 2012 that reduced the size of drug-free zones from 1,000 to 300 feet and made them applicable only between 5 a.m. and midnight. Brownsberger said the effect on sentencing and the state prison population was dramatic, dropping the number of school zone–enhanced sentences by two-thirds or more.

"If you looked at the houses of correction populations going back six or eight years ago, you would have seen a lot of people doing school zone sentences," Brownsberger says. "Now, most people who are doing mandatory minimum sentences are there for drunk driving or gun charges. There just aren't a lot of school zone charges being booked."

Many advocacy groups would like to see drug-free school zones eliminated entirely or at least severely limited, but they've had to settle for compromises to assuage more conservative lawmakers. While several states have reduced the number of locations that turn the surrounding area into such a zone and have limited the types of offenses the statutes cover, none have shrunk the perimeter to less than 100 feet.

Harris, the Tennessee lawmaker, says Indiana is a model for his own reform efforts. A bill to reduce the Volunteer State's drug-free zones from 1,000 feet to 500 feet passed the state Senate last year but died in the state House. Legislators are trying again this year, with support from a coalition of conservative and liberal advocacy groups.

"It's an uphill battle in Tennessee," Harris says. "The good news is there are conservative states out there that are taking a look at these laws and making changes, because they're not a good use of resources."

Statistics in this story regarding age, race, sentence length, and the number of Tennesse inmates were derived from data obtained from the Tennessee Department of Corrections. Vector data on the size and locations of drug-free school zones were also obtained from the Tennessee state government. All of the data used in this story can be viewed and downloaded on Github.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Myth of the Playground Pusher."

Show Comments (28)