Before Calling People Racist or Politically Correct, Let's Remember That Law Enforcement Has Conflicting Definitions of the Word 'Terrorism'

Reluctance to use the T-word after mass killings can be routinely found whether perpetrators are white or brown.

I was still getting up to speed on this morning's awful news from Las Vegas when the first of many Twitter fights erupted in my feed, beginning with this pair of tweets from Slate's Jamelle Bouie:

Essentially, by the definition currently in common currency, a white person cannot be a terrorist.

— Jamelle Bouie (@jbouie) October 2, 2017

This prompted The Week's Damon Linker to reply, "Amazing how when you assume everything is about race, suddenly everything is about race," and we were off to the proverbial races. Glenn Greenwald, for instance, tweeted: "Everyone knows (even if won't admit it) that in the early stages of mass shooting, 'no signs of terrorism' means: 'shooter isn't Muslim.'"

This is emphatically not true.

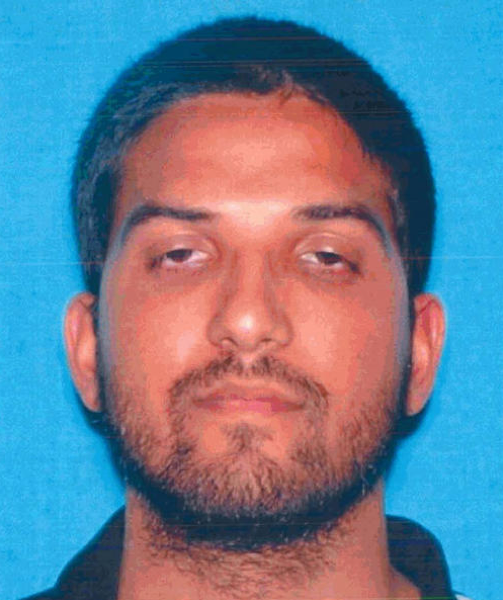

"Is this a terrorist incident? We do not know," David Bowdich, assistant director of the FBI's Los Angeles field office, said after Syed Farook and Tashfeen Malik had been killed in a shootout with police following their murder of 14 people in San Bernardino nearly two years ago. "Have you noticed the government still is not calling this terrorism?" Rush Limbaugh scoffed at the time.

So before falling once again into a rut of ritualized response, it's worth examining what different people mean at different times by the word terrorism. Start with July 4, 2002.

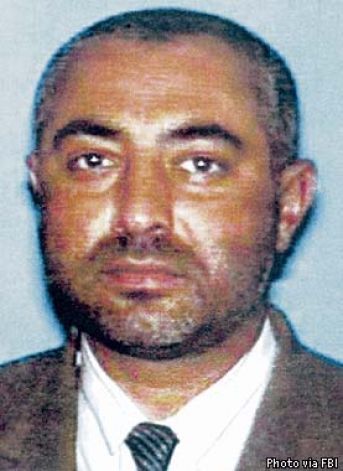

Back then, when America's nerves were still raw to the bleeding point after 9/11, a 41-year-old Egyptian national and Irvine resident named Hesham Mohamed Hadayet took two guns and a hunting knife to LAX, and opened fire at the ticket counter of the Israeli airline El Al, killing two and wounding four. Prior to targeting Israelis on America's Independence Day, Hadayet, who U.S. immigration officials knew had been arrested back in Egypt for association with an Islamist group, had reportedly expressed anger at a neighbor for flying an American flag after Sept. 11, and also decorated his front door with a "Read the Koran'' bumper sticker.

Despite all this information being known by the morning of July 5, then-White House spokesman Ari Fleischer said that day, "There is no evidence, no indication at this time that this is a terrorist." This echoed comments from L.A. Mayor James Hahn ("We have no reason to believe that this was a terrorist activity"), the office of Gov. Gray Davis ("isolated incident"), and several law enforcement officials.

At the time, I was apoplectic about what I felt was a paternalistic condescension toward the public's ability to handle the truth during a moment of crisis (note that the act was judged to be terrorism months later by the FBI and Dept. of Justice). But with the passage of years and the dreary compilation of subsequent murderous acts, it has become obvious that, especially during moments of intense crisis, the law enforcement definition of "terrorism" has little in common with the dictionary description of "The unlawful use of violence and intimidation, especially against civilians, in the pursuit of political aims."

For instance, look at the Telegraph piece Bouie linked to support his initial "ruled out terrorism" claim:

When asked by a reporter if it was an act of terrorism, Sheriff [Joseph] Lombardo said: "No, not at this point. We believe it was a local individual. He resides here locally."

"I'm not at liberty to give you his place of residence yet, because it's an ongoing investigation, we don't know what his belief system was at this time. … Right now we believe he is the sole aggressor at this point and the scene is static."

Sole aggressor, local individual, unknown belief system. As in the cases of Farook and Hadayet, an official during the initial moment of investigative confusion, local panic and national grief seems to be defining "terrorism" as "an act coordinated with a probably overseas-based terrorist organization." Such a definition would rule out any number of attacks we easily recognize now as terroristic, from Timothy McVeigh's Oklahoma City truck bombing to possibly even Nidal Hasan's murder of 13 people in Fort Hood.

So why are authorities frequently slow to use the T-word? When you set aside the intense emotions surrounding racism and political correctness, an easy set of answers lurks in plain sight: They don't want people to freak out about still being under attack. Motives as yet aren't crystal clear. They are still investigating a matter that may very well be classified as terrorism—maybe involving those links to outside groups—later on.

The disputed meaning of terrorism, is, at this late date, sadly not new. Nor, almost as sadly, is the tendency to interpret the resulting paradoxes as evidence of the opposing side's worst possible faith.

Show Comments (76)