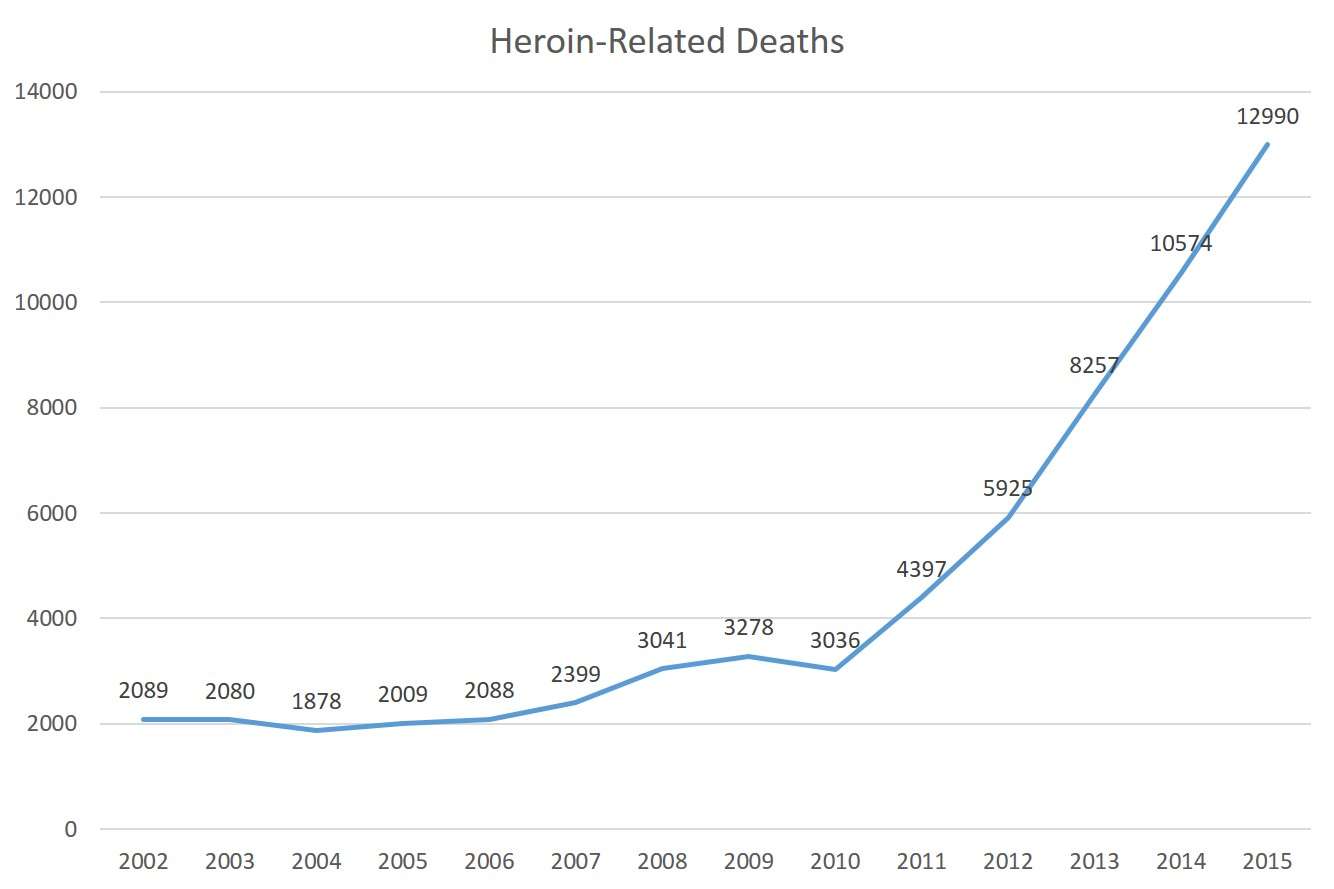

Heroin-Related Deaths Rise As Heroin Use Falls

The divergence reinforces the case for harm reduction.

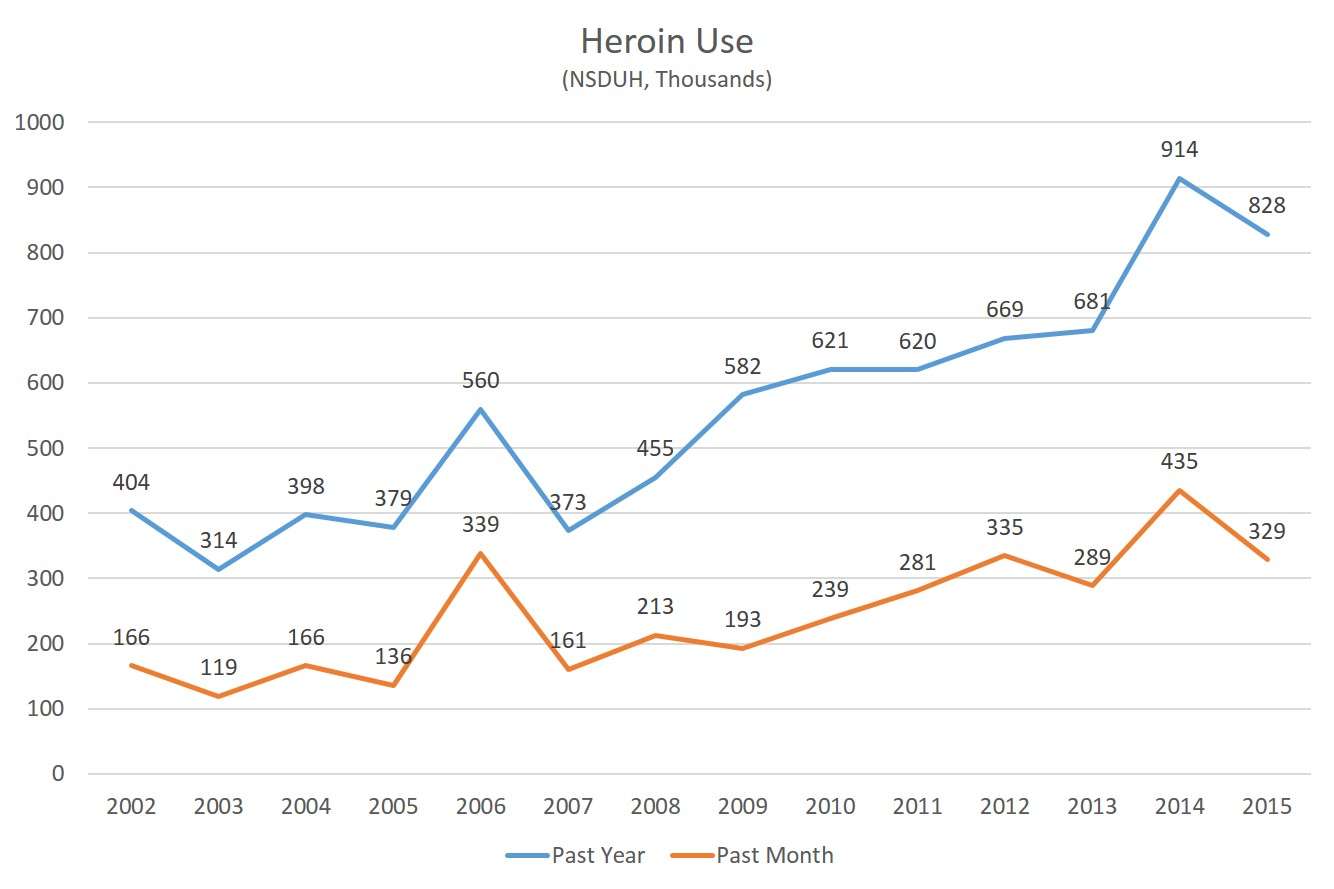

CDC numbers released last week indicate that the number of heroin-related deaths in the United States rose from 10,574 in 2014 to 12,990 in 2015. That 23 percent increase occurred even though heroin use, as measured by the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), declined last year. This development underlines a phenomenon I've noted before: Heroin use is more dangerous than it used to be. Since 2002, according to NSDUH, the number of heroin users has more than doubled, but the number of drug poisoning deaths involving heroin has more than sextupled. To put it another way, heroin users are about three times as likely to die from drug poisoning as they were in 2002.

Several factors may help explain this striking development. As the government cracked down on nonmedical use of prescription painkillers, a lot of opioid users switched to heroin, and these new heroin users were not accustomed to the black market's inconsistent potency. One reason heroin can be stronger than expected is the addition of the synthetic narcotic fentanyl, which has become more common in recent years. "Overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone rose from 5,544 in 2014 to 9,580 in 2015, an increase of 73 percent," the CDC notes. "This category of opioids is dominated by fentanyl-related overdoses, and recent research indicates the fentanyl involved in these deaths is illicitly manufactured, not from medications containing fentanyl." Fentanyl aside, most heroin-related deaths involve drug mixtures, and it's possible the new heroin users are more inclined to combine it with other depressants.

The shift to the black market can't be the whole story, because there was a similar divergence between consumption of legal opioids and deaths involving them. Nonmedical use of these drugs fell slightly between 2002 and 2014, when the number of deaths involving them rose by 150 percent. It seems clear that fatalities are not a simple function of use rates, which means policies aimed at driving down consumption may not be the most effective way to reduce deaths. Such efforts may even have the opposite effect, as the crackdown on painkillers apparently did by driving opioid users to heroin.

Taking these points into account, a new set of recommendations from the Drug Policy Alliance (DPA) suggests several ways to make opioid use less dangerous, including wider distribution of the overdose-reversing opioid antagonist naloxone, legal reforms to protect bystanders who report overdoses, "drug checking services" that would alert users to the presence of adulterants such as fentanyl, and supervised injection facilities, where people can consume drugs in a safe and sanitary setting monitored by medical professionals. DPA says "SIFs have been rigorously studied and found to reduce the spread of infectious disease, overdose deaths, and improperly discarded injection equipment, and to increase public order, access to drug treatment and other services, and to save taxpayer money." DPA also suggests "heroin-assisted treatment," which gives addicts access to pharmaceutical-quality heroin. It says "research has shown that HAT can reduce drug use, overdose deaths, infectious disease, and crime, while saving money and promoting social integration."

These harm reduction measures go beyond "just say no" to grapple with the factors that make opioid use more dangerous than it has to be. It's doubtful that the Trump administration, which so far leans strongly toward old-fashioned prohibitionism, will be open to such ideas. But any response to the rise in opioid-related deaths that does not address the divergence between consumption and fatality trends will be missing an important part of the picture.

Show Comments (29)