The Second Amendment, the Bill of Rights, and the Constitution

What the historical evidence says about the Second Amendment and individual rights.

In 1803 a distinguished Virginia jurist named St. George Tucker published the first extended analysis and commentary on the recently adopted U.S. Constitution. Though it is mostly forgotten today, Tucker's View of the Constitution of the United States was a major work in its time. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, generations of lawyers and scholars would reach for Tucker's View as a go-to constitutional law textbook.

I was reminded of Tucker's dusty tome in recent days after reading one liberal pundit after another smugly assert that the original meaning of the Second Amendment has nothing whatsoever to do with individual rights. Slate's Dahlia Lithwick, for example, denounced the individual rights interpretation of the Second Amendment as a "a hoax" peddled in recent years by the conniving National Rifle Association. Likewise, Rolling Stone's Tim Dickinson complained that "the NRA's politicking has warped the Constitution itself" by tricking the Supreme Court into "recast[ing] the Second Amendment as a guarantee of individual gun rights."

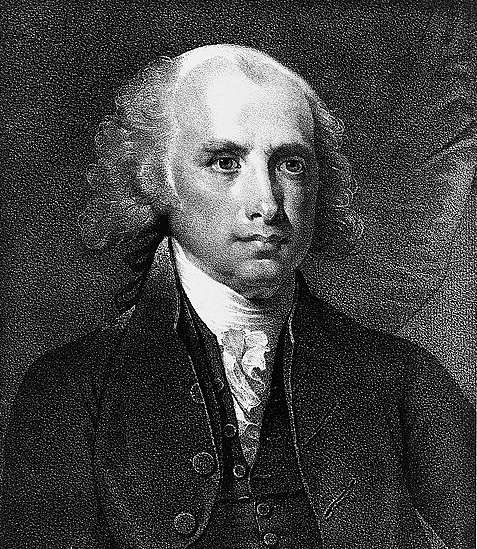

Old St. George Tucker never encountered any "politicking" by the NRA. A veteran of the Revolutionary war and a one-time colleague of James Madison, Tucker watched in real time as Americans publicly debated whether or not to ratify the Constitution, and then watched again as Americans debated whether or not to amend the Constitution by adopting the Bill of Rights. Afterwards Tucker sat down and wrote the country's first major constitutional treatise. And as far Tucker was concerned, there was simply no doubt that the Second Amendment protected an individual right to arms. "This may be considered as the true palladium of liberty," Tucker wrote of the Second Amendment. "The right of self-defense is the first law of nature."

The individual rights interpretation of the Second Amendment was widely held during the founding era. How do we know this? Because the historical evidence overwhelmingly points in that direction. For example, consider the historical context in which the Second Amendment was first adopted.

When the Constitution was ratified in 1789 it lacked the Bill of Rights. Those first 10 amendments came along a few years later, added to the Constitution in response to objections made during ratification by the Anti-Federalists, who wanted to see some explicit protections added in order to safeguard key individual rights. As the pseudonymous Anti-Federalist pamphleteer "John DeWitt" put it, "the want of a Bill of Rights to accompany this proposed system, is a solid objection to it."

James Madison, the primary architect of the new Constitution, took seriously such Anti-Federalist objections. "The great mass of the people who opposed [the Constitution]," Madison told Congress in 1789, "dislike it because it did not contain effectual provision against encroachments on particular rights." To remove such objections, Madison said, supporters of the Constitution should compromise and agree to include "such amendments in the constitution as will secure those rights, which [the Anti-Federalists] consider as not sufficiently guarded." Madison then proposed the batch of amendments that would eventually become the Bill of Rights.

What "particular rights" did the Anti-Federalists consider to be "not sufficiently guarded" by the new Constitution? One right that the Anti-Federalists brought up again and again was the individual right to arms.

For example, Anti-Federalists at the New Hampshire ratification convention wanted it made clear that, "Congress shall never disarm any Citizen unless such as are or have been in Actual Rebellion." Anti-Federalists at the Massachusetts ratification convention wanted the Constitution to "be never construed…to prevent the people of the United States, who are peaceable, from keeping their own arms."

Meanwhile, in the Anti-Federalist stronghold of Pennsylvania, critics at that state's ratification convention wanted the Constitution to declare, "that the people have a right to bear arms for the defense of themselves and their own State, or the United States, or for the purpose of killing game; and no law shall be passed for disarming the people or any of them, unless for crimes committed, or real danger of public injury from individuals."

One of the central purposes of the Second Amendment was to mollify such concerns by enshrining the individual right to arms squarely within the text of the Constitution. Just as the First Amendment was added to address fears of government censorship, the Second Amendment was added to address fears about government bans on private gun ownership.

Like it or not, the idea that the Second Amendment protects an individual right is as old as the Second Amendment itself.

Show Comments (190)