Why the Merrick Garland Nomination Is a Disappointment to Progressives

Left-wing activists complain about Obama's SCOTUS pick.

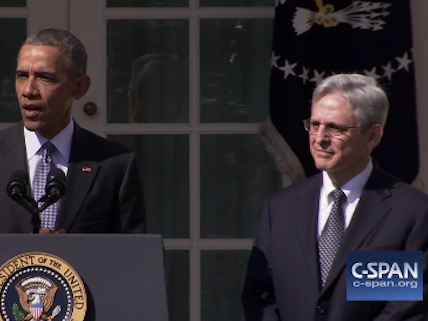

President Barack Obama said he selected Judge Merrick Garland to replace the late Justice Antonin Scalia on the U.S. Supreme Court because of Garland's sterling credentials. "I've selected a nominee who is widely recognized not only as one of America's sharpest legal minds," Obama announced, "but someone who brings to his work a spirit of decency, modesty, integrity, even-handedness, and excellence."

Unfortunately for Obama, not all of his liberal allies seem to see it that way. "Judge Garland's background does not suggest he will be a progressive champion," protested Murshed Zaheed, political director of the liberal activist group CREDO. Left-wing pundit Mark Joseph Stern offered a similarly disapproving view. "President Barack Obama's nomination of Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court is extremely disappointing," Stern griped at Slate. Even Terry O'Neill, president of the National Organization for Women and normally a staunch friend to the Obama administration, took a shot at the president's pick. "It's unfortunate that President Obama felt it was necessary to appoint a nominee to the Supreme Court whose record on issues pertaining to women's rights is more or less a blank slate," O'Neill complained.

Why are so many progressives voicing complaints about the Merrick Garland nomination? One plausible explanation comes courtesy of liberal legal scholar Jeffrey Rosen, a contributing editor for The Atlantic and the president of the National Constitution Center. In Rosen's view, the Garland nomination counts as a "victory for judicial restraint." That victory is precisely why lots of progressives are unhappy. Here's Rosen:

Garland clerked for two legendary judges—Henry Friendly and William Brennan. But he has embraced the deferential jurisprudence of Friendly, rather than the activist jurisprudence of Brennan. (Chief Justice John Roberts, who also clerked for Friendly, said admiringly, "Any time Judge Garland disagrees, you know you're in a difficult area.") As Damon Root, the libertarian writer accurately concluded, "While Garland is undoubtedly a legal liberal, his record reflects a version of legal liberalism that tends to line up in favor of broad judicial deference to law enforcement and wartime executive power." That's why Garland's nomination may discomfit libertarians and progressives who want to use the courts to impose contested visions of social change on a divided nation. But, in any rational world, it should lead traditional conservative and liberal defenders of a limited judicial role to dance in the streets.

The idea behind judicial deference is that unelected judges should be extremely wary about overturning laws enacted by the democratically accountable branches of government. As Rosen suggests, modern progressives do sometimes favor this minimal approach to judging. In 2012, for example, as the Supreme Court was weighing the constitutional merits of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, President Obama lectured the Court on why it had no business taking the "unprecedented extraordinary step of overturning a law that was passed by a strong majority of Congress." Chief Justice John Roberts ultimately came to the same conclusion, voting to uphold Obamacare on the deferential grounds that, "it is not our job to protect the people from the consequences of their political choices."

Most progressives probably thought that sort of judicial deference sounded exactly right. Yet just one year later, those same progressives probably thought differently when the Supreme Court weighed the constitutional merits of another law "passed by a strong majority of Congress," the Defense of Marriage Act. In that case, United States v. Windsor, the Court adopted a wholly different approach to judging, gave no deference to Congress, and struck down a central provision of a democratically enacted federal statute. Not exactly "a limited judicial role" for SCOTUS.

Which brings us back to the Merrick Garland nomination. If Garland really is a true believer in judicial deference, that means Garland thinks judges should consistently tip the scales in favor of lawmakers, including in cases in which lawmakers have passed legislation that progressive activists don't like (such as regulations that govern abortion providers).

In other words, the Garland nomination ended up delivering a surprising and unwelcome message to Obama's progressive supporters, Namely, progressives can't have it both ways and still claim to favor any sort of coherent judicial philosophy. No wonder they're upset.

Show Comments (33)