Did ExxonMobil Lie About What It Knew About Climate Change?

What did the company know, and when did it know it?

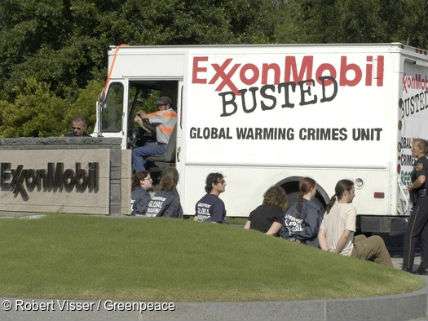

New York State Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman issued subpoenas on Wednesday to oil giant ExxonMobil demanding that it turn over internal communications regarding what the company knew about the risks of climate change. Shades of Watergate: What did the company know, and when did it know it? The investigation by the grandstanding attorney general follows in the wake of a long-standing claim by some environmental activists that oil companies have sought to confuse the debate over climate change in the service of their profits.

On top of this, activists have been more recently pushing the notion of a "carbon bubble" stemming from the argument that in order to protect the climate most hydrocarbon assets will have to remained buried. As a consequence, companies that own those assets will become bankrupt. Maybe. But in its 2014 World Energy Outlook report, the International Energy Agency projects that global oil production will rise from 90 million barrels to 104 million barrels per day by 2040 and that fossil fuel use will increase overall by 37 percent.

In any case, Schneiderman is specifically seeking evidence that ExxonMobil knew, but failed to warn its shareholders, about climate risks to its assets.

In recent months, activists claimed to have uncovered "smoking gun" documents from ExxonMobil showing that the company did in fact know that emitting carbon dioxide by burning oil and natural gas was causing climate change. The activists cite a 1977 memo by Exxon scientist J.F. Black which summarizes:

What is considered the best presently available climate model for treating the Greenhouse Effect predicts that a doubling of the C02 concentration in the atmosphere would produce a mean temperature increase of about 2°C to 3°C over most of the earth. The model also predicts that the temperature increase near the poles may be two to three times this value.

Interestingly, this is about the temperature range for a doubling of atmospheric CO2 in the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report is 1.5°C to 4.5°C. The 1977 memo also notes the many uncertainties about the sources of CO2, the primitive state of climate models, and so forth.

ExxonMobil has made the early climate change memos cited in the recent reporting available to the public. The executives in the company were clearly aware that future climate change caused by burning fossil fuels could become a significant problem in the coming century. On the other hand, the internal reports do take into account important uncertainties about climate prognostication.

In a recent article, the Los Angeles Times makes much of the fact that in the early 1990s, ExxonMobil researchers and engineers were evaluating how global warming might effect the company's arctic operations. As the LA Times however reports one the lead engineers ultimately …

…did not recommend making investment decisions based on those scenarios, because he believed the science was still uncertain. However, he advised the company to consider and incorporate potential "negative outcomes," including a rise in the sea level, which could threaten onshore infrastructure; bigger waves, which could damage offshore drilling structures; and thawing permafrost, which could make the earth buckle and slide under buildings and pipelines.

Smoking gun? Not really. It would be surprising for executives and engineers not to evaluate all kinds of scenarios as they consider long term capital investments. And ExxonMobil researchers and executives were not alone in their uncertainty about the future trajectory of climate change. In 1992, the National Academy of Sciences issued a big report, Policy Implications of Greenhouse Warming: Mitigation, Adaptation and the Science Base, that, among other things, noted:

Increases in atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations probably will be followed by increases in average atmospheric temperature. We cannot predict how rapidly these changes will occur, how intense they will be for any given atmospheric concentration, or, in particular, what regional changes in temperature, precipitation, wind speed, and frost occurrence can be expected. So far, no large or rapid increases in the global average temperature have occurred, and there is no evidence yet of imminent rapid change. But if the higher GCM projections prove to be accurate, substantial responses would be needed, and the stresses on this planet and its inhabitants would be serious.

Over the decades, company executives did frequently point to uncertainties in the developing climate science. But this seems have changed after the IPCC issued its Fourth Assessment of climate science in 2006 which stated:

Most of the observed increase in global average temperatures since the mid-20th century is very likely due to the observed increase in anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations.

After that report, for the first time (that I could find at least), the company's 2006 annual report noted the risks of climate change to its business:

Political and Legal Factors: The operations and earnings of the Corporation and its affiliates throughout the world have been, and may in the future be, affected from time to time in varying degree by political and legal factors including … laws and regulations related to environmental or energy security matters, including those addressing alternative energy sources and the risks of global climate change…

Is that enough to squelch Schneiderman's investigation? As the New York Times notes:

Whether Exxon Mobil began disclosing the business risks of climate change as soon as it understood them is likely to be a major focus of the New York case. The people with knowledge of the case said the attorney general's investigators were poring through the company's disclosure filings made since the 1970s, but were focusing in particular on recent statements to investors.

Exxon Mobil has been disclosing such risks in recent years, but whether those disclosures were sufficient has been a matter of public debate.

That is indeed the debate.

The bottom line: Schneiderman's investigation is likened to the litigation against Big Tobacco that did lie about the health dangers of smoking for decades. The result of that litigation is annual payments to the states totaling $206 billion dollars over 25 years. There is little doubt that Schneiderman is looking for an even bigger pay day from Big Oil.

For more background on how I came to change my mind about the possible dangers of man-made global warming see my 2006 article, "Confessions of an Alleged ExxonMobil Whore."

Show Comments (130)