Louisiana Tries to Bring Back Electric Chair and Make Lethal Injection Drugs Secret, Luckily Fails at Both

A bill that would have brought one of the toughest lethal injection secrecy regimes in the country to Louisiana was pulled by its sponsor just hours before the 2014 legislative session came to an end yesterday.

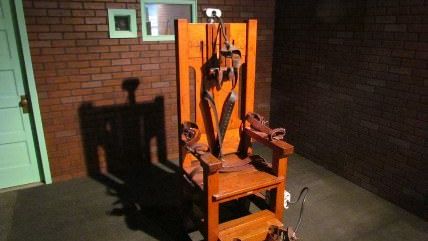

The bill, HB 328, has a peculiar genealogy. It started out as a backdoor reauthorization of the electric chair in the Bayou State. After a few weeks, the legislature decided Gruesome Gertie wasn't worth resurrecting and abruptly changed course.

In April, the legislature rewrote HB 328 to give cover to Louisiana's Department of Corrections for the sloppy, illicit practices officials had attempted to get away with over the past few months—such as illegally purchasing lethal drugs out of state (from the dubiously named compounding pharmacy, The Apothecary Shoppe, in Oklahoma last year), changing its drug cocktail protocol without giving sufficient notice (as in the case of child-killer Christopher Sepulvado, whose execution has been stayed twice over this issue), and keeping information about the execution drugs a secret (even from inmates set to be strapped to the table). The bill also would have prohibited any public inquiry into botched executions.

The real reasons for scrapping the legislation—after both houses of the Louisiana legislature approved it—are still unclear. Republican state Rep. Joe Lopinto told reporters yesterday, "We passed a resolution today to study this issue. There's no reason for us to rush through and pass piecemeal legislation that will only be a short-term fix for something that needs a long-term solution."

A growing number of other states have adopted secrecy measures regarding the procurement of execution drugs, such as Oklahoma and Missouri, in response to a shortage of the drugs made by the only FDA approved manufacturers, who stopped making the drugs available for executions.

Among the states to adopt secrecy measures is Georgia, which passed a law that makes the identity of the pharmacy that supplies the state with its execution drugs a "state secret." That law has faced a number of legal challenges from lawyers, but the state supreme court upheld the law last month on the grounds that it made executions "more timely and orderly." Legal challenges to secrecy measures are currently pending in numerous other states.

The Guardian, Associated Press, and three local newspapers have filed suit over Missouri's lethal injection secrecy measures, asserting that the public has the right to know "the type, quality and source of drugs used by a state to execute an individual in the name of the people," under the first Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

The fact that Louisiana's lethal injection secrecy bill was scrapped yesterday signals that at least some state legislators, like Lopinto, are willing to reconsider the costs and potential unintended consequences of allowing states to conduct its most grisly business behind closed doors. Let's hope that others follow suit.

Show Comments (46)