Suspicion of Government Isn't Racist, But People Suspicious of Government Are? What?

Honestly, Jonathan Chait has me perplexed when he insists that I was wrong to characterize him as claiming that skepticism toward the state is all about internalized racism. To the contrary, says he, (keep in mind that, to him, any suspicion of government is "conservative") "while conservatism and racism may be historically, sociologically, and psychologically inseparable, it is absolutely necessary to debate conservative ideas on their own terms."

So far as I can tell, his argument is that anti-statism is like a unicorn: it can maintain its innocence only when unsullied by contact with people. Once it suffers a human embrace, though, it becomes tainted.

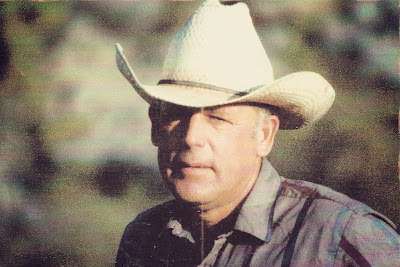

But it's true that people can bring bad associations to other, unrelated ideas. Chait triumphantly points to Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy (pictured above right), of tussling with the Bureau of Land Management fame, for making hideous comments about African-Americans, including "they abort their young children, they put their young men in jail, because they never learned how to pick cotton."

That's contemptible stuff. It was also contemptible when progressives merged pseudo-scientific racist notions with their ideology and implemented them as policy to such a degree that Booker T. Washington wrote during Woodrow Wilson's presidency that he had, "never seen the colored people so discouraged and bitter as they are at the present time."

Indeed, the later New Deal, often touted as a pinnacle of progressive policy, was largely a raw deal for minorities.

But just as advocates of a large and forceful state aren't bound by the bigotry of a William Jennings Bryan or a Woodrow Wilson, so Cliven Bundy's moronic notions about race don't rope in those who are skeptical about just that sort of government.

Even before Bundy opened his mouth to reveal a yawning chasm of idiocy, I noted that his standoff with the feds was a sideshow to a more contemporary debate over the control of western lands.

"Why do all these people with strong antipathy toward the federal government turn out to be racists?" asks Chait. Maybe it's because the cameras and journalists focus on one loudmouth on horseback, even as representatives of nine state governments meet in Salt Lake City at the Legislative Summit on the Transfer of Public Lands.

If all skeptics of the state are tainted by racism, does that include the oft-cited (by libertarians) Lysander Spooner, who was an abolitionist as well as anarchist? He argued that natural law forbade slavery, offered free legal services to escaped slaves, and even supported guerrilla warfare to defeat the institution.

He also said that the laws of the state "have no color of authority or obligation."

Suspicion of state power has a history, and it's certainly not reliant on bigotry.

Chait's reliance on one research study to tie (presumably anti-government) political sentiments in the Old South to the legacy of slavery founders on the facts of history. Writing last year in Jacobin about the Tea Party movement, Seth Ackerman pointed out:

The notion that Southern Democrats in Congress during the middle third of the century were progenitors of ideological Tea Party-style anti-government extremism cannot withstand a glance at their actual voting records.

In the 1930s and afterwards, Southern members almost unanimously insisted on shielding the South's social system, based on labor-surplus agriculture and formalized racial hierarchy, from any federal policies that might erode it. But once those guarantees were granted, usually through quiet negotiations in committee or within the Democratic leadership, those legislators openly and overwhelmingly supported the New Deal.

He added, "there was simply no mass electoral base in the South for the kind of free-enterprise fundamentalism that could thrive in historically prosperous northern regions like rural upstate New York or small-town central Ohio."

If a legacy of slavery is responsible for southern opposition to Washington, D.C., today, was it also responsible for southern support for Social Security and other elements of the welfare state?

Or perhaps liberalism, like anti-statism, is also innocent only until touched by the people it attracts, and sullied by their support.

Show Comments (304)