There Should Be No 'Punishment' Phase When a Culture War Ends

Dozens of supporters of gay marriage, including many noted journalists and scholars, have signed on to a statement today calling for an end to the kind of public outrage that haunted ex-Mozilla CEO Brendan Eich when people discovered he once donated money to the opposing side.

The full statement is posted at Real Clear Politics, and the signatories include many names recognizable here at Reason: Jonathan Rauch, Paypal's Peter Thiel, Eugene and Sasha Volokh (and other contributors to The Volokh Conspiracy), Andrew Sullivan, Charles Murray, Reason Contributing Editor Cathy Young. The letter calls for advocacy and debate, but an end to retributive responses to those who have opposed (or still oppose) same-sex marriage recognition. In the section titled "Disagreement Should Not Be Punished," they argue:

We prefer debate that is respectful, but we cannot enforce good manners. We must have the strength to accept that some people think misguidedly and harmfully about us. But we must also acknowledge that disagreement is not, itself, harm or hate.

As a viewpoint, opposition to gay marriage is not a punishable offense. It can be expressed hatefully, but it can also be expressed respectfully. We strongly believe that opposition to same-sex marriage is wrong, but the consequence of holding a wrong opinion should not be the loss of a job. Inflicting such consequences on others is sadly ironic in light of our movement's hard-won victory over a social order in which LGBT people were fired, harassed, and socially marginalized for holding unorthodox opinions.

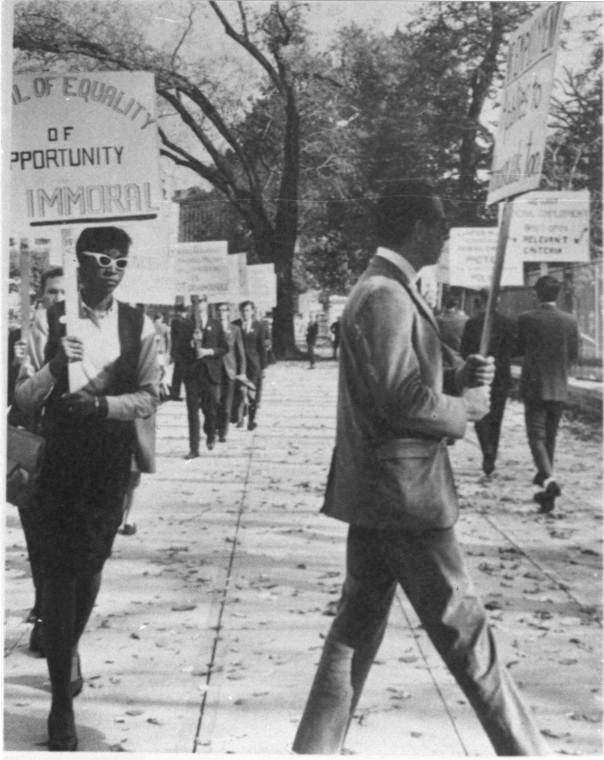

During the debate over whether what happened to Eich was appropriate—and very frequently in the debate on recognizing gay marriage itself—supporters of how the conflict ended with Eich stepping down invoked interracial marriage. Would we have supported Eich if he was opposed to interracial marriage? How is opposing same-sex marriage different from opposing interracial marriage? Indeed, the issue was immediately raised in the comment thread after signatory Dale Carpenter posted an excerpt at The Volokh Conspiracy. Should a CEO opposed to interracial marriage be immune from any sort of consequences from such a position?

Since the laws against interracial marriage were struck down so many years ago, it's appropriate to respond: Who, actually, was punished for being on the wrong side of that debate? Did people who opposed race-mixing lose their jobs for supporting the wrong candidates? Can anybody point to CEOs who were fired back in the '60s or '70s for supporting some racist candidate somewhere? I have done a bit of a stab at trying to track down any info that such outcomes happened, but that would seem to take a lot more time than I have as a blogger.

To the extent that those particular civil rights battles ended, I don't recall there being a punishment phase afterward. The battles were certainly punishment enough. Those people on the wrong side—and there were millions of them—didn't go anywhere. They continued on with their lives under new laws and probably most of them eventually came around on the issue, or at least kept it to themselves. Winning a culture war isn't like winning an actual war. You're not stopping an invasion (or initiating one). When the war is over, the participants are still around and they still have to negotiate a way to live together. That realization is why the end of a culture war simply can't have some sort of Nuremberg Trials. There isn't an equivalent. You have to live next door to people who may have extremely different views from yours. Sometimes, those views were actually the majority view at one point. If you try to initiate a punishment phase, why would your opponents then agree to stop fighting and accept your victory?

Nobody who knows the history of the gay movement in the United States should countenance people being punished by their employers for the way they express themselves, unless they value revenge more than liberty (some probably do, sadly). The conclusion of the letter notes:

LGBT Americans can and do demand to be treated fairly. But we also recognize that absolute agreement on any issue does not exist. Franklin Kameny, one of America's earliest and greatest gay-rights proponents, lost his job in 1957 because he was gay. Just as some now celebrate Eich's departure as simply reflecting market demands, the government justified the firing of gay people because of "the possible embarrassment to, and loss of public confidence in…the Federal civil service." Kameny devoted his life to fighting back. He was both tireless and confrontational in his advocacy of equality, but he never tried to silence or punish his adversaries.

Now that we are entering a new season in the debate that Frank Kameny helped to open, it is important to live up to the standard he set. Like him, we place our confidence in persuasion, not punishment. We believe it is the only truly secure path to equal rights.

The tragedy was not that this sort of workplace treatment happened to gays and lesbians (or that it still happens). It was that it happened to anybody at all.

Show Comments (129)