Nicholas Kristof Says Busting Johns Is the Key to Shutting Down the World's Oldest Profession

Is there any police activity more pointless and pathetic than a "sting" aimed at people seeking to buy arbitrarily proscribed products or services? It is bad enough when the government criminalizes a transaction—a wager, a drug purchase, the exchange of money for sex—that violates no one's rights. When cops go out of their way to enforce that prohibition by tricking people into talking about transactions that will never occur, they manufacture "crimes" that are doubly phony. So how should we view armed agents of the state who invite people to engage in peaceful exchange, only to pounce on them with guns and handcuffs?

New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof thinks they're heroes. Consider the breathless opening of his latest column equating prostitution with "human trafficking":

Several police officers are waiting in a hotel room, handcuffs at the ready, when they get the signal. A female undercover officer posing as a prostitute is with a would-be customer in an adjacent room, and she has pushed a secret button indicating that they should charge in to make the arrest.

The officers shove at the door connecting the rooms, but somehow it has become locked. They can't get in. The undercover officer is stuck with her customer. Tension soars. Curses reverberate. A million fears surge.

Then, suddenly, the door frees and the police officers rush in and arrest a graying 64-year-old man, Michael. His smugness shatters and turns to bewilderment and shock as police officers handcuff his hands behind his back.

Exciting stuff. It takes a brave cop to join with several of his heavily armed colleagues in ambushing a defenseless 64-year-old who has committed the unpardonable offense of being smug in the presence of a fake prostitute.

How does Kristof justify this unprovoked violence? In his usual slippery way. "Some women sell sex on their own," he concedes, "but coercion, beatings and recruitment of underage girls are central to the business as well." Then he mentions "a 14-year-old girl in Queens" who ran away from home and was "locked up by pimps and sold for sex." Although they threatened to kill her if she tried to escape, "after three months she managed to call 911."

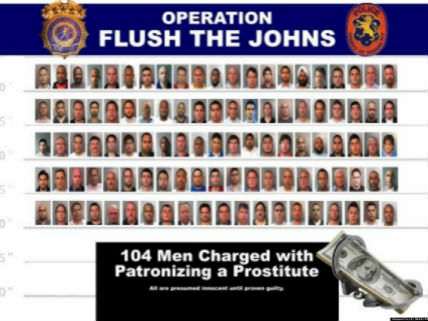

What exactly does that 14-year-old girl have to do with poor Michael, the john arrested in a Chicago hotel room after responding to an online ad placed by the Cook County Sheriff's Office? Unless the ad referred to an underage girl held against her will, there is no reason to think that Michael or any of the other men arrested in prostitution stings are complicit in such crimes. But they must suffer, Kristof says, because "police increasingly recognize that the simplest way to reduce the scale of human trafficking is to arrest men who buy sex." He insists "that isn't prudishness or sanctimony but a strategy to dampen demand."

This strategy—cops posing as prostitutes—has been a joke and a cliché for as long as I've been alive, but Kristof considers it the cutting edge of innovative policing. If targeting customers is all it takes to eradicate black markets, why do they still exist? People have been buying and selling sex for thousands of years, but Kristof seems to think they will stop if only we can get enough pretty police officers to impersonate hookers. He calls sting operations "marvels of efficiency"—which they are, assuming you want to produce futile arrests and gratuitous humiliation.

Kristof claims men who pay for sex, even when the transactions involve consenting adults, "perpetuate" crimes against women, because some prostitutes are forced into the business by threats of violence. By the same logic, people who buy automobiles perpetuate car theft, and people who hire domestic help perpetuate slavery. If anyone is perpetuating prostitution-related violence, it is prohibitionists like Kristof, who insist on maintaining a black market in which both buyers and sellers face unnecessary risks and victims are treated like criminals.

Melissa Gira Grant covered "The War on Sex Workers" in the February 2013 issue of Reason.

Show Comments (96)