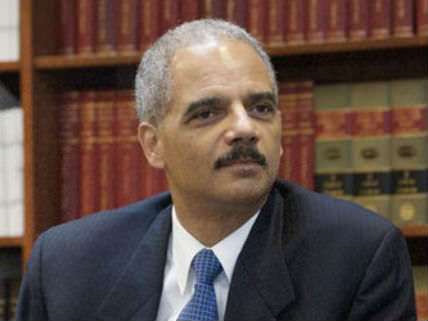

Eric Holder Condemns 'Stand Your Ground' but Does Not Blame It for Zimmerman's Acquittal

In a speech to the NAACP today, Attorney General Eric Holder mentioned George Zimmerman's acquittal in the death of Trayvon Martin, portraying the shooting as the result of racial profiling. That view is tempting and common, but it does not fit the facts as well as you might think. Judging from the recording of his 911 call, Zimmerman deemed Martin suspicious enough to contact the police before he got a good enough look to verify his race. Although Zimmerman's neighborhood had been plagued by burglars identified as young black men, the evidence that race was a factor in the shooting was so thin that the judge did not allow the prosecution to bring it up during his trial.

The juror interviewed by CNN's Anderson Cooper last night said the issue of race did not play any role in deliberations. "We never had that discussion," she said, adding that "I think George would have reacted the exact same way" to Martin if he had been white, Hispanic, or Asian. The issue was not Martin's skin color, she said, but what Zimmerman perceived as suspicious behavior by a young man he did not recognize: "He was cutting through the back. It was raining. [Zimmerman] said he was looking in houses as he was walking down the road….I think he profiled anybody who came in and acted strange." Take that with a grain of salt if you like, since the all-female jury did not include any blacks. [Whoops—yes, it did.] But while Zimmerman bears responsibility for creating the circumstances that led to his violent confrontation with Martin (a point the juror also made), it is debtable whether racial profiling explains his decision to follow the teenager.

Although Holder sees clear racial overtones to Zimmerman's actions, he did not try to make the case that the shooting illustrates the folly of Florida-style self-defense laws, possibly because that case is so hard to make. Indeed, Holder explicitly separated the "stand your ground" debate from the Zimmerman case:

Separate and apart from the case that has drawn the nation's attention, it's time to question laws that senselessly expand the concept of self-defense and sow dangerous conflict in our neighborhoods. These laws try to fix something that was never broken. There has always been a legal defense for using deadly force if—and the "if" is important—no safe retreat is available.

But we must examine laws that take this further by eliminating the common sense and age-old requirement that people who feel threatened have a duty to retreat, outside their home, if they can do so safely. By allowing and perhaps encouraging violent situations to escalate in public, such laws undermine public safety. The list of resulting tragedies is long and—unfortunately—has victimized too many who are innocent. It is our collective obligation—we must stand our ground—to ensure that our laws reduce violence, and take a hard look at laws that contribute to more violence than they prevent.

All that is eminently debatable, starting with Holder's claim that the right to stand your ground is a dangerous new invention. As Michael J.Z. Mannheimer, a law professor at Northern Kentucky University, noted shortly after the shooting of Trayvon Martin became a national story:

The law in America has always been ambivalent about the duty to retreat, with about half the States at any given time recognizing the duty to retreat and about half abrogating it. This is not a new development. Moreover, even where there is no duty to retreat, it is still a requirement that the defendant reasonably believed that deadly force was necessary to prevent the imminent use of deadly physical force. And even in a retreat jurisdiction, the prosecution generally must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant knew he could retreat with complete safety. So, in practice, there is not a whole lot of daylight between retreat and no-retreat jurisdictions.

Presumably that is why Bernie de la Rionda, the chief prosecutor in the Zimmerman trial, says "the law really hasn't changed all that much" since 2005, when the Florida legislature abolished the duty to retreat for people attacked in public places. At least Holder is not listing Trayvon Martin's death as one of the "resulting tragedies" he attributes to such legislation. Still, you have to wonder why "it's time" to question "stand your ground" the week after Zimmerman's acquittal if the two things have nothing to do with each other.

Show Comments (177)