Bloomberg's Latest Nanny-State Initiative Could Be Overturned Too

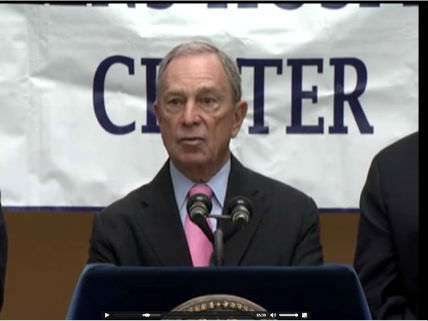

Smarting from a state judge's decision overturning his beloved big beverage ban, New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg is seeking solace in good old-fashioned anti-smoking activism. Today he urged the New York City Council to approve an ordinance requiring retailers who sell tobacco to hide it from their customers, lest the sight of cigarette packages lure children into a deadly habit. "New York City has dramatically lowered our smoking rate," Bloomberg declared, "but even one new smoker is one too many." Jim Calvin, president of the New York Association of Convenience Stores, questioned Bloomberg's theory on the origin of smokers:

I'm disputing the far-fetched assumption that because young people see a product in a store, the sight of it compels them to start smoking. Many of our stores are licensed to sell beer. Does the sight of it encourage underage drinking? The sight of lottery tickets to gamble? The sale of condoms to engage in premarital sex?

Bloomberg's proposal may be vulnerable on legal as well as empirical grounds. Although his wish to make tobacco products invisible does depend on action by the city council, the absence of which helped doom his drink diktat, the rule he seeks seems to run afoul of the Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act. That 1965 law bars states and municipalities from imposing any "requirement or prohibition based on smoking and health…with respect to the advertising or promotion of cigarettes." The policy Bloomberg wants certainly seems to fit that description, especially since his premise is that cigarette packages promote smoking.

Bloomberg should have anticipated this complication, since the same federal statute was the basis for a successful challenge to another one of his anti-smoking initiatives, a requirement that merchants display icky, city-designed posters warning customers about the health consequences of the habit and urging them to quit. Like Bloomberg's limit on soda servings, the poster mandate was imposed by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene without input from the city council. In 2010 U.S. District Judge Jed Rakoff ruled that it was pre-empted by federal law, and last year the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit agreed.

Because that case was resolved on statutory grounds, neither Rakoff nor the appeals court addressed the plaintiffs' First Amendment claims, based on compelled speech and the government's commandeering of valuable point-of-sale advertising space. Bloomberg's latest initiative, aimed at banning what he clearly views as persuasive speech for the sake of the children, also raises First Amendment issues. As I noted earlier today, the Supreme Court has not looked kindly on obstructing information about tobacco products aimed at adults because it might be seen by children.

Show Comments (84)