Justice Memo: Assault Weapon Ban "Would Not Have a Large Impact on Gun Homicides"

The National Rifle Association's Institute for Legislative Action is having a lot of fun with a National Institute of Justice memo on gun control strategies, and well it should. Of the big three proposals on the table in Congress, the memo says that even "a complete elimination of assault weapons would not have a large impact on gun homicides," that restrictions on high-capacity magazines without grabbing the ones already in circulation "would nearly eliminate any impact" and that the effectiveness of universal background checks depends on requiring the impossible dream of gun registration and making it easy and attractive for people to comply. The memo also dismisses gun "buybacks" and recommends controls on ammunition sales — fears of which have already fueled a buying frenzy for ammo and reloading supplies.

The "Summary of Select Firearm Violence Prevention Strategies" (PDF) was penned January 4 of this year by Greg Ridgeway, the Deputy Director of the National Institute of Justice, which is the research arm of the Department of Justice. With regard to the sort of mass shooting that set off the current jihad in D.C. against self-defense rights, Ridgeway writes:

On average there are about 11,000 firearm homicides every year. While there are deaths resulting from accidental discharges and suicides, this document will focus on intentional firearm homicides. Fatalities from mass shootings (those with 4 or more victims in a particular place and time) account on average for 35 fatalities per year.

The memo doesn't mention that the murder rate in 2011 was 4.8 per 100,000, and has been declining for decades. That's half the rate that prevailed during the Great Depression and down from a modern peak of 10.2 per 100,000 in 1980.

What the memo does delve into are proposals, big and small, for legally restricting guns and ammunition, and their potential for reducing crime. Of Sen. Dianne Feinstein's favorite hobbyhorse, a ban on "assault weapons," Ridgeway says:

Guns are durable goods. The 1994 law exempted weapons manufactured before 1994. The exemption of pre-1994 models ensures that a large stock, estimated at 1.5 million, of existing weapons would persist. Prior to the 1994 ban, assault weapons were used in 2-8% of crimes. Therefore a complete elimination of assault weapons would not have a large impact on gun homicides.

He goes on to write that a ban on "assault weapons" might be effective if you didn't grandfather the existing stock and successfully bought all of them from their owners. Except … earlier in the memo Ridgeway concluded:

Gun buybacks are ineffective as generally implemented. 1. The buybacks are too small to have an impact. 2. The guns turned in are at low risk of ever being used in a crime. 3. Replacement guns are easily acquired. Unless these three points are overcome, a gun buyback cannot be effective.

Even there, he points out that the massive "Australia buyback appears to have had no effect on crime" except for the happy fact that there have been no mass shootings since then. But mass shootings weren't exactly common events before the buyback, so …

For the also popular bans on high-capacity magazines, Ridgeway sees theoretical promise, but no practical way to make them effective — especially in the short term.

In order to have an impact, large capacity magazine regulation needs to sharply curtail their availability to include restrictions on importation, manufacture, sale, and possession. An exemption for previously owned magazines would nearly eliminate any impact. The program would need to be coupled with an extensive buyback of existing large capacity magazines.

Again, buybacks — assuming the ones turned in are not the ones "at low risk of ever being used in a crime." And assuming that people don't just make their own new magazines.

Universal background checks could have an effect only if coupled with gun registration and near-perfect implementation, suggests Ridgeway. That's because:

… informal transfers dominate the crime gun market. A perfect universal background check system can address the gun shows and might deter many unregulated private sellers. However, this does not address the largest sources (straw purchasers and theft), which would most likely become larger if background checks at gun shows and private sellers were addressed.

The problem with "perfect" is that nothing is perfect, and existing state-level requirements of this sort have been widely ignored. He describes how a California law requiring that all transfers take place through federally licensed dealers has been ineffective because "[t]here are disincentives to following the law in California ($35 and a waiting period). Such a process can discourage a normally law-abiding citizen to spend the time and money to properly transfer his or her firearm to another." I would think that political resistance is also a barrier to enforcement, just as it has been to registration.

What does Ridgeway think might work? He offers a limp endorsement for gun registration, both in and of itself and as a necessary precondition for universal background checks, but he has to know that, historically, compliance among existing gun owners has been rock bottom. More promising, he suggests, would be restricting and tracking ammunition sales, both to track the flow of ammunition and as a lead to who owns guns. "Ammunition purchase logs are a means of checking for illegal purchases and for developing intelligence on illegal firearms."

Note, though, that criminals need far less ammunition than recreational users. Doing background checks on ammunition purchasers is likely to drive criminals to the black market to buy the few rounds they may need for threatening people, while legal shooters get to negotiate yet another bureaucratic hurdle, and hope that the records are accurate.

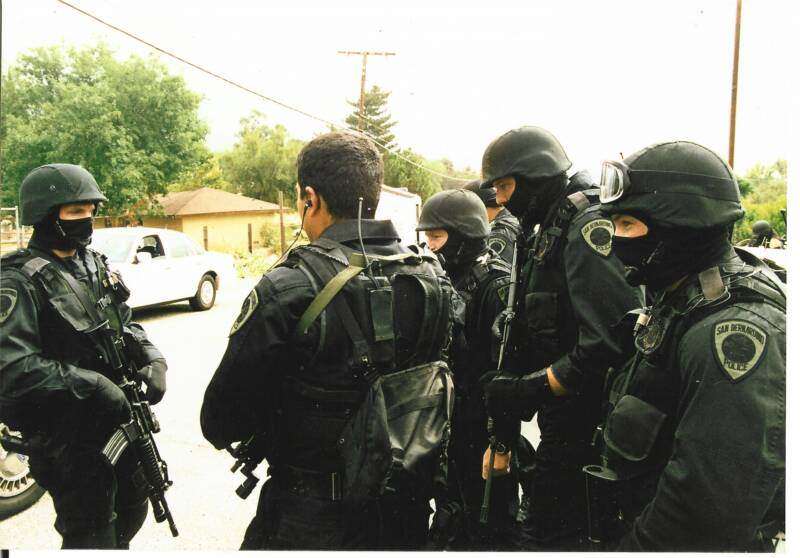

Police in California already knock on doors of people suspected of illegally owning guns. According to the Los Angeles Times, "[t]he agents show up in heavily armed teams, wearing black jumpsuits bulked up by bulletproof vests." As you might expect, they sometimes arrive at the wrong address and scare the shit out of people. So far, they've counted on intimidation to get them into homes, since they have insufficient grounds for warrants. The prospect of extending this program nationally, so that armed gangs show up at homes based on a mismatch in official records between calibers registered as owned and ammunition purchased, is enough to … well, to keep ammunition and reloading supplies flying off the shelves in anticipation of that not-so-happy day.

The NIJ memo is a great lesson in what gun control policies don't work and why they fail —and perhaps a pointer to what the powers that be might try next.

Show Comments (16)