Movie Reviews: Sully and The Beatles: Eight Days a Week – The Touring Years

Profiles in courage and '60s pop delirium.

The well-known tale of Captain Chesley "Sully" Sullenberger—the US Airways pilot who bravely ditched his plane in the Hudson River off of Manhattan in 2009 in order to save the lives of his 155 passengers—is a real feel-good story. It makes you feel good just knowing there are selflessly committed individuals like Sullenberger still around.

But the story's basic action—from the time Sully realized that a large flock of geese had clogged up both of his engines to the time his plane touched down on the water—only lasted about three minutes. The veteran pilot subsequently built a memoir around the incident, and it became a bestseller. But now Clint Eastwood has tried to build a movie around it, and even at 95 minutes the picture feels stretched and padded.

The digital effects Eastwood has used to help recreate the plane's emergency descent into the river are exciting—the action seems alarmingly real, and the terrified frenzy aboard the plummeting aircraft and then out in the water as the passengers await rescue is grippingly edited. But while Tom Hanks was a good choice to play Sullenberger—with white hair and a trim mustache, he radiates decency and self-deprecation—he's also a problem. Decency and self-deprecation aren't very interesting to watch—the character lacks complexity, and he doesn't evolve. Hanks' Sullenberger is a stand-up guy, and not much more. "I'm just a man who was doing his job," he tells a TV host in the wake of his celebrated exploit.

But Hanks is never less than likeable (as is Aaron Eckhart, in a strong performance as Sully's copilot, Jeff Skiles). The movie has more crucial flaws. Given the brevity of the central action, Eastwood is compelled to inflate the story surrounding it, to meager narrative purpose. So we see not only the ditching of Sully's aircraft, but also alternative versions of it that appear to him in nightmares and daydreams, with his plane diving down into midtown Manhattan, banging into skyscrapers along the way. (Echoes of the 9/11 Twin Towers attack seem clearly intended—"It's been a while since New York had news this good," says one of Sully's fellow officers, "especially with an airplane in it." But Eastwood's motivation for summoning these feelings seems banal.)

We also get a few aftermath shots of Sully jogging through Times Square and along a river promenade, lost in thought about whether he did the right thing. And he makes repeated odd calls to his worried wife (Laura Linney) back home in California. (Each time he gets her on the line he tells her he has to go.) There's also an overextended mini-story involving an air traffic controller who's reduced to tears when he loses contact with Sully's foundering plane.

In need of conflict, Eastwood and writer Tom Komarnicki have set up a team of investigators from the National Transportation Safety Board as the villains of the piece. Led by a sneeringly abrasive character named Porter (Mike O'Malley), they're determined to prove that instead of ditching in the Hudson, Sully could just as easily—and more safely—have returned to La Guardia Airport, his point of departure, or changed course for New Jersey's nearby Teterboro Airport. Computer simulations seem to prove the preferability of these alternatives, and the NTSB team is convinced that Sullenberger was recklessly wrong. (The real-life NTSB officials deny they had it in for Sully, and say they were simply following standard investigative procedure.) These second-guessing government bureaucrats are perfect targets for Eastwood's expected contempt; but they're so hostile to Sully that when they immediately collapse into admiration for him after their dubious computer recreations turn out to be flawed, the movie slumps like a mis-handled soufflé.

Chesley Sullenberger is clearly a man of cool-headed courage, an actual hero who deserved all the plaudits he received. Whether he, or we, needed this movie is another question.

The Beatles: Eight Days a Week – The Touring Years

The Beatles' music can never again be heard for the first time, in its original cultural context. Which is too bad, because a sense of revelation—of new sounds and new harmonic ideas being unveiled—was a key reason for the worldwide excitement the group provoked.

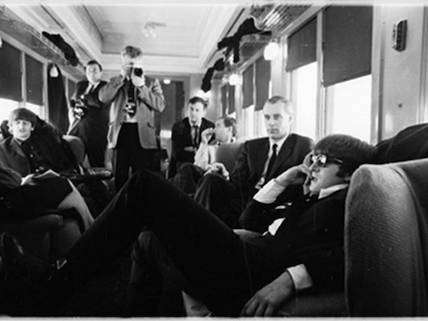

In assembling his awkwardly titled The Beatles: Eight Days a Week – The Touring Years, director Ron Howard must have known he couldn't make this music entirely new again—we've been drenched in it for the past 50-odd years. But Howard has been able to draw on what must have been miles of rare and in some cases previously unseen footage from period media reports, international TV libraries, fan hoardings, and the Beatles themselves, and he uses it to depict Beatlemania, in all of its mad passion, in a really electrifying way. More instructively, he also provides a detailed illustration of how the nonstop hysteria that grew up around these four musicians finally ground them down and brought an end to their touring days in August of 1966.

There are no real surprises here—the Beatles' story is so deeply embedded in pop-music consciousness that its most familiar beats can only be restated. Still, there's terrific footage following the group from the Cavern Club to the Continent and on to America, Tokyo, the Philippines and beyond. The music we hear is naturally all hits, from "She Loves You" and "Can't Buy Me Love" to "Ticket To Ride" and "Day Tripper." And the vintage audio tracks have been so expertly cleaned up and remastered that they've acquired a new power (you can hear the individual instruments clearly now, and the live-concert vocal harmonies have a fresh, tingling brilliance).

John Lennon and George Harrison are heard from only in old footage, of course (we see Lennon "apologizing" against his will at a press conference for his "more popular than Jesus" remark); but there are new interviews with Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr, and bits of testimony from a number of famous Beatles fans. Some of these outside observers seem randomly chosen (Eddie Izzard? Malcolm Gladwell?), but some offer unexpected illuminations. Whoopi Goldberg, whose mother surprised her with hard-to-get tickets to the Beatles' Shea Stadium concert in 1965, says that, for a little black fan, "They gave me this feeling that everybody was welcome." And Sigourney Weaver has a sweet memory of her own Beatles-concert experience, surrounded by other hysterically delighted and in some cases weeping teenage fans. "I was feeling everything a girl can feel," she says.

I was unaware that the Beatles' tour contract for a swing through Florida emphasized their refusal to play to segregated audiences. And I don't believe I've previously seen the press-conference clip in which a reporter asks the boys why they think they're so insanely popular. (The answer: "If we knew, we'd start another group and be managers.") The movie can't fully retrieve that long-ago time, but it's fun to watch in this one.

Show Comments (17)