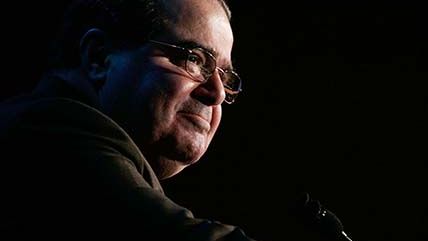

How Antonin Scalia Shaped—and Misshaped—American Law

The mixed legacy of the late Supreme Court justice

Antonin Scalia, who died in February at age 79, will be remembered as a giant of American law. Appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1986 by President Ronald Reagan, Scalia left his mark on some of the most significant issues facing the judiciary, from the debate over competing methods of constitutional interpretation to the clash over the proper role of the courts. Politicians, judges, and lawyers—not to mention generations of future law students—will be grappling with Scalia's handiwork for decades (or more) to come.

For many Americans, Scalia will be perhaps best remembered for his caustic dissents in cases dealing with issues such as abortion rights and gay marriage. When the Supreme Court struck down Texas' controversial ban on "homosexual conduct" in 2003, for instance, Scalia made headlines with his statement that the Court's decision in Lawrence v. Texas was "the product of a Court that has largely signed on to the so-called homosexual agenda." Scalia did not mean that as a compliment.

Yet despite his reputation as a right-wing culture warrior, Scalia was equally outspoken in other areas of the law that are commonly (if erroneously) associated with the legal left. When it came to the Fourth Amendment and its protections against unreasonable searches and seizures, Scalia frequently led the way in rejecting the pro-government interpretations favored by state and federal law enforcement. In 2014's Navarette v. California, for example, the Supreme Court ruled that a traffic stop and resulting drug bust that occurred thanks to an anonymous telephone tipster "complied with the Fourth Amendment." Scalia thought otherwise. In his dissent, Scalia attacked the majority for producing "a freedom-destroying cocktail" that privileges an anonymous and uncorroborated tip over a core constitutional right. "All the malevolent 911 caller need do is assert a traffic violation, and the targeted car will be stopped, forcibly if necessary, by the police." That ugly scenario, Scalia declared, "is not my concept, and I am sure it would not be the Framers', of a people secure from unreasonable searches and seizures."

Likewise, in his 2001 majority opinion in Kyllo v. United States, Scalia came out swinging against the use of warrantless thermal imaging to detect signs of marijuana cultivation inside of a suspect's house. "Where, as here, the Government uses a device that is not in general public use, to explore details of the home that would previously have been unknowable without physical intrusion," Scalia wrote, "the surveillance is a 'search' and is presumptively unreasonable without a warrant."

Justice Scalia wrote many influential opinions during his three decades on the Court, but the one he often said he was most proud of was his 2008 majority opinion in District of Columbia v. Heller, the landmark case in which the Supreme Court struck down Washington's handgun ban and ruled that the Second Amendment protects an individual right, not a collective one, to keep and bear arms.

Scalia was proud of Heller not only because it vindicated the Second Amendment, which until then had been in a sort of legal limbo at the high court, but because he saw it as a "vindication of originalism," the theory of legal interpretation that he did so much to help popularize and establish. Under originalism, constitutional provisions are supposed to be interpreted according to their original meaning at the time they were ratified. As Scalia argued in his 1997 book, A Matter of Interpretation, "if the people come to believe that the Constitution is not a text like other texts; that it means, not what it says or what it was understood to mean, but what it should mean…well, then, they will look for qualifications other than impartiality, judgment, and lawyerly acumen in those whom they select to interpret it. More specifically, they will look for judges who agree with them as to what evolving standards have evolved to; who agree with them as to what the Constitution ought to be."

Unfortunately, Scalia did not always practice the originalist philosophy he liked to preach. Most notably, when the Supreme Court was asked in 2010 to examine the original meaning of the 14th Amendment in the gun rights case McDonald v. Chicago, Scalia not only backtracked on originalism; he actually mocked the libertarian lawyer Alan Gura for daring to ask the Supreme Court to seriously address the original meaning of the 14th Amendment in the first place.

"What you argue," Scalia scoffed at Gura during oral argument, is "contrary to 140 years of our jurisprudence." (Needless to say, 140 years of Supreme Court jurisprudence is not exactly the same thing as fidelity to the text of the Constitution.) "Why do you undertake that burden," Scalia asked, "instead of just arguing substantive due process, which as much as I think it's wrong, I have—even I have acquiesced in it?"

It was an unfortunate episode, as even Scalia's biggest fans will reluctantly concede. After all, there was Scalia, the Court's foremost advocate of originalism, falling back on questionable precedents while refusing to consider the originalist arguments that were properly presented before him in a major constitutional case. To make matters worse, Scalia announced his intentions to acquiesce in a legal approach he himself considered to be un-originalist and "wrong."

Similarly, despite his previous votes in support of federalism, Scalia concurred with the liberal majority in 2005's Gonzales v. Raich, in which Congress's power to regulate interstate commerce was deemed expansive enough to outlaw the cultivation and consumption of medical marijuana inside the state of California, where such activity was perfectly legal under state law.

Whether you agreed with him or not, Antonin Scalia was always a force to be reckoned with. For better and for worse, he shaped the course of American law.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "How Antonin Scalia Shaped—and Misshaped—American Law."

Show Comments (0)