What Libertarians Get Wrong About American History

American history is not an essentially libertarian story.

Understanding history as best we can is important for obvious reasons. It's particularly important for libertarians who want to persuade people to the freedom philosophy. In making their case for individual freedom, mutual aid, social cooperation, foreign nonintervention, and peace, libertarians commonly place great weight on historical examples most often drawn from the early United States. So if they misstate history or draw obviously wrong conclusions, they will discredit their case. Much depends therefore on getting history right.

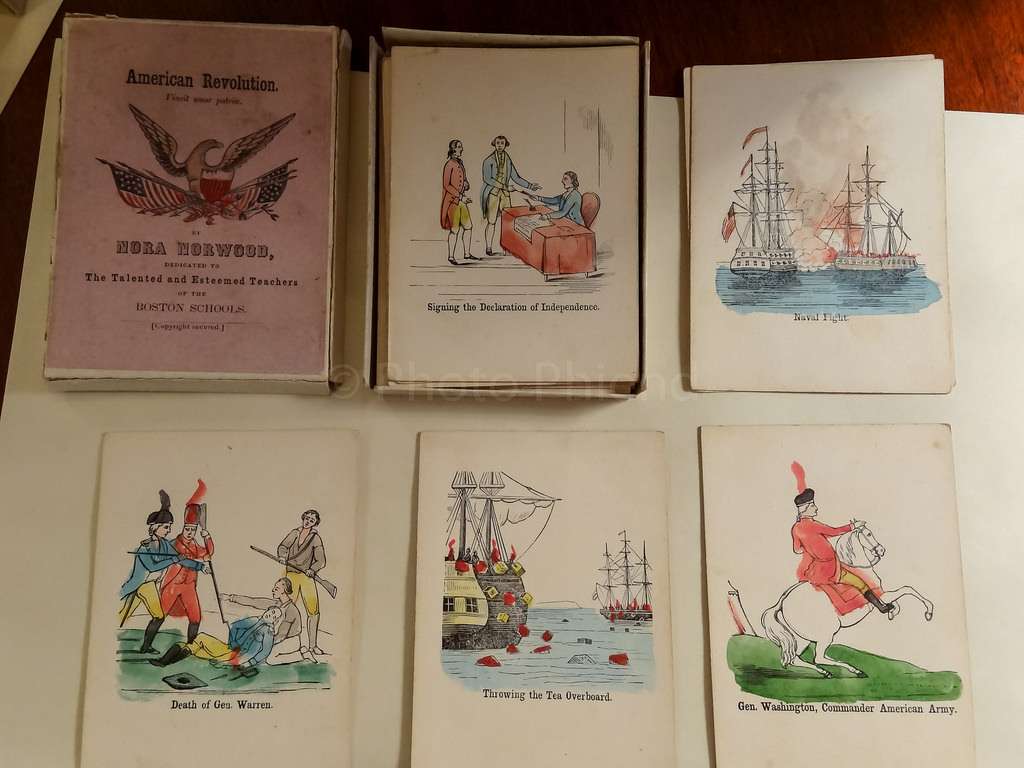

Libertarians naturally sense that their philosophy will be easier to sell to the public if they can root it in America's heritage. This is understandable. Finding common ground with someone you're trying to persuade is a good way to win a fair hearing for your case. Well-known aspects of early American history, at least as it is usually taught, fit nicely with the libertarian outlook; these include Thomas Paine's pamphlets, the opening passages of the Declaration of Independence, and popular animosity toward arbitrary British rule.

The problem arises when libertarians cherry-pick confirming historical anecdotes while distorting or ignoring deeper disconfirming evidence. The drawbacks to grounding the case for freedom in historical inaccuracies should be obvious. If a libertarian with a shaky historical story encounters someone with sounder historical knowledge, the libertarian is in for trouble. The point of discussing libertarianism with nonlibertarians is not to feel good but to persuade. If the history is wrong, why should anyone believe anything else the libertarian says?

The damage done to a young person new to libertarianism is particularly tragic. Discovery of the libertarian philosophy, especially when combined with the a priori approach of Austrian economics, can make young libertarians feel virtually omniscient and ready for argument on any relevant topic. When such libertarians venture into empirical areas—such as history—they are prone to use ideology or the a priori method as guides to the truth. If libertarians with this frame of mind run into serious students of history, the results can be traumatic. The disillusionment can be so great that a young libertarian might decide to keep quiet from then on or give up the philosophy entirely. A libertarian who might have become a powerful advocate is lost to the movement. Thus we owe young libertarians the most accurate historical interpretation possible. Gross oversimplification sets them up for disaster. It's like sending a sheep to the slaughter.

Where are libertarians likely to go wrong when it comes to history? By and large, it's in presenting American history as an essentially libertarian story. [This goes for the industrial revolution in England also.] We've all heard it: British imperial rule violated the rights of the American colonists, who—fired up by the ideas of John Locke— drove out the British, adopted limited government and free markets through the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, and pursued a noninterventionist foreign policy; this lasted until the Progressives and New Dealers came along. It's not that everything about this overview is wrong; it contains grains of truth. Americans were upset by British arbitrary rule (which violated the accustomed "rights of Englishmen"), and Lockean ideas were in the air. But much of the rest of the libertarian template is more folklore than history.

For one thing, the early state governments were hardly strictly limited. Libertarians too readily confuse the desire for a relatively weak central government with the desire for strict limits on government generally. For many Americans a strong central government was seen as an intrusion on state and local government to which they gave their primary allegiance. But that is not a libertarian view; it depends on what people want state and local governments to do. (Jonathan Hughes's The Governmental Habit Redux is helpful here.)

Libertarians also wish to believe that the early national government was fairly libertarian-ish. With the exception of slavery and tariffs, it is often explained, government was strictly limited by the Constitution and Bill of Rights. Slavery of course was an egregious exception, which was enforced by the national government, and passionate opponents agitated against it. Tariffs were part of a larger system of government intervention, which many libertarians simply ignore. Nor were these the only serious exceptions to an otherwise libertarian program. But before getting to that, we must say something about the Constitution.

Libertarians of course know that the Constitution was not the first charter of the United States. But many of them rarely talk about the first one: the Articles of Confederation, which was adopted before the war with Britain ended. Under the Articles the weak national quasi-government lacked, among other powers, the powers to tax and regulate trade, which is why I call it a quasi-government. It obtained its money from the states, which did have the power to tax. So while it could not steal money, it nonetheless subsisted on stolen money. [The Articles were no libertarian document.]

Advocates of a unified nation under a powerful central government, such as James Madison, tried immediately to expand government power under the Articles but got nowhere. The centralists eventually arranged for the Federal Convention in Philadelphia, where the Constitution—the acknowledged purpose of which was to produce more, not less, government—was adopted. The libertarian Albert Jay Nock called the convention a coup d'etat because it was only supposed to amend the Articles. Instead, the men assembled tore up the Articles, crafted an entirely new plan that included the powers to tax and to regulate trade, and changed the ratification rules to permit merely nine states to carry the day, instead of the unanimous consent required for amendments to the Articles.

The Constitution that was sent to the state conventions for ratification drew the opposition of people who soon were known as Antifederalists. (Those who favored the Constitution's strong central government were the real antifederalists, but they grabbed the popular "federalist" label first.) The Antifederalists lodged many serious objections to the proposed Constitution, only one of which was the lack of a bill of rights. They saw danger in, among other things, the broad language of the tax power, the general-welfare clause, the supremacy clause, and the necessary-and-proper clause—all of which, in their view, harbored unenumerated powers, contrary to Madison's declaration. The Bill of Rights, which the first Congress later added to the already-ratified Constitution, did not even attempt to address the Antifederalists' major objections. [History, I submit, has confirmed their predictions of tyranny.]

Many libertarians who presumably know this story are strangely silent about it. On the rare occasion they mention the Articles, they say little more than that unspecified problems with them prompted the Philadelphia convention and adoption by the assembled demigod-like Founding Fathers of that ingenious architecture of limited government we know as the Constitution. Then, the story continues, the libertarian masses' objection to the lack of a bill of rights led to the adoption of the first ten amendments to protect our liberties. All was well until …

One would expect a "government" that lacked the power to tax and regulate trade to be of more interest to libertarians. One would also expect libertarians to be suspicious of a plan to address those alleged deficiencies. Instead, the Articles typically are shunted aside and the Constitution is lauded as a historic achievement in the struggle for liberty. That is odd indeed.

I think we can explain this lack of interest in the Articles by noting that it fits poorly into the mainstream libertarian narrative about America. After all, it would be hard to praise the Constitution as a reasonably good attempt to limit government while acknowledging that it replaced a political arrangement under which the government could neither tax nor regulate trade. In that context the Constitution looks like a step backward not forward.

This also explains an otherwise inexplicable phenomenon: the lack of interest among many libertarians in the most libertarian of the early Americans: the Antifederalists. [Admittedly, not all Antifederalists were as libertarian as the best of them were.] Libertarians who have what has been called a Constitution fetish could hardly embrace the principled libertarian opponents of their beloved Constitution. The story wouldn't make sense. [See Jeffrey Rogers Hummel's "The Constitution as Counter-Revolution" (PDF).]

Many libertarians also like to paint the early national period in pacific colors, quoting Washington, Jefferson, and Madison against standing armies, alliances, and war. In contrast to today, we're told, the American people and their "leaders" hated empire and imperialism. But this is misleading. From the start America's rulers, with public support, were bent on creating at least a continental empire, including Canada, Mexico, and neighboring islands. Some had the entire Western Hemisphere in their sights. Americans were not anti-empire; they were anti-British Empire—or, more accurately, anti-Old-World Empire. They did not want to be colonists anymore. America's future rulers saw their revolution as a showdown between an exhausted old imperial order and the rising imperial order in the New World. [Of course, it was called an Empire of, or for, Liberty.] Continental expansion—conquest—required an army powerful enough to "remove" the Indians from lands the white population coveted. "Removal"of course meant brutal confinement—so the Indian populations could be controlled—or extermination. This government program constituted a series of wars on foreign nations in the name of national security.

Continental expansion also was accomplished by acknowledged unconstitutional acts, such as the national government's acquisition of the huge Louisiana territory from Napoleon, which placed the inhabitants under the jurisdiction of the U.S. government without their consent. The War of 1812 was motivated in part by a wish to take Canada from the British. [See my "The War of 1812 Was the Health of the State," part 1 and part 2.] A few years later, American administrations began to built up the army and navy in order to bully Spain into ceding another huge area. The U.S. government thus gained jurisdiction over a vast territory reaching to the Pacific Ocean, from which the navy could project American influence and power to Asia. [In light of this empire-building, the Civil War can be seen as empire preservation.]

National security was always on the politicians' minds: the exceptional nation, whose destiny was manifest, could never be safe if surrounded by Old World monarchies and their colonial possessions. American politicians generally hoped to acquire those possessions through negotiation, but war—which major political figures believed was good for the national spirit—was always an option, as Secretary of State John Quincy Adams let the Spanish know in no uncertain terms in the years before 1820. Had Spain been more defiant of Adams, the Spanish-American War would have occurred 78 years earlier than it did.

We can acknowledge that leading politicians were domestic liberals, relatively speaking, in that they did not want the national government to intrude (as the British did) arbitrarily into the private affairs of Americans. The resulting personal freedom can account for the rising prosperity. But libertarians tend to push this point too far. In fact, with the War of 1812—slightly more than two decades after ratification of the Constitution—America's rulers, including former Jeffersonians, favored expanded powers for the national government, including a central role in the economy to create a national market and a national-security state. A pushback by the older Jeffersonian wing of the American political establishment took place briefly, but the centralists soon won the day for good. Alexander Hamilton and Henry Clay were surely smiling.

The government's role in the economy came in the form of aggressive trade policy, internal improvements (with land grants to cronies), and more. The trade wars preceding and associated with the War of 1812 convinced most Americans that government was indispensable to making the United States a global commercial power. Free trade did not mean the laissez faire of Richard Cobden but rather a comprehensive government effort to open— by force if necessary—foreign markets to American merchants. In short order the objective changed from open markets and reciprocity to neomercantilism. Privileges for well-connected business interests were present all along the way. [Grover Cleveland complained about this in 1888.]

I am not saying that if early Americans could have seen today's America, they would have been pleased. Some clearly would not have been. I am saying that what they favored—national and commercial greatness—prepared the way for what America has become, whether or not they would have favored it. If you will the end, you will the means. You cannot build a continental empire and a worldwide political and military presence without planting the seeds of powerful government at home, a national-security state, and all that they require, including income taxation, regulation, central banking, and a welfare state to ameliorate the worst hardships of the system's victims, if only to tamp down radical resistance.

If libertarians mischaracterize this history, they discredit the case for liberty not only by appearing uninformed, but also by associating the freedom philosophy with a story that is more corporatist and imperialist than libertarian. As I've said before, the good old days lie ahead.

This piece originally appeared at Sheldon Richman's "Free Association" blog.

Show Comments (324)