Will Robots Take Our Jobs?

For now humans make sub-par robots and robots make sub-par humans.

Today's robots may lack emotions, but they have quite a knack for rousing heated passions within their prevailing meaty overlords. Ray Kurzweil and his devotees daydream of a singularity rapture, when benevolent machine intelligence will overtake human knowledge to saturate and awaken the universe. On the gloomier side of the existential spectrum, Elon Musk recently donated $10 million to the Future of Life Institute to fight the rise of killer robots. Either way, these thinking machines are expected to be a pretty big deal. But we can hardly wait for cosmic horror or transhumanist actualization to start asking the tough questions: Will the robots take our jobs?

Robots are nothing new. Industrial robots have been employed in manufacturing for about as long as polyester has been belabored in fashion. But unlike synthetic fibers, synthetic laborers have gotten much better over time. Digital employees consistently become cheaper, smarter, and more prevalent with each doubling of the number of transistors crammed into microprocessors. At their most salient, robots look a lot more like Kiva's dumb and deferent deliverybots shuttling packages along Amazon warehouse floors than Neill Blomkamp's charming CHAPPiE. But let's not be crass humanoid supremacists, here. Digital workers are much more than mere metal reflections of ourselves.

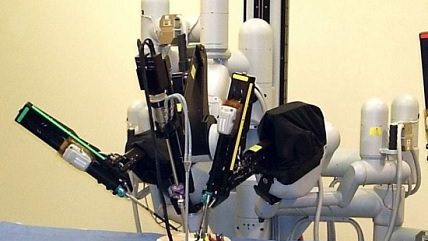

They can be advanced algorithms, expertly detecting patterns and performing rote directives far more precisely than even the best legal clerks, beat journalists, or financial traders. They are also connected devices, everyday objects retrofitted with sensors, cameras, and wireless access points to digitize and measure the latent data around us—for fun and (more often) profit. And they are autonomous crafts shipping goods and people safely across the globe by land, air, and sea. They will slash costs in health care, transit, manufacturing, media, and municipal services by the trillions in a dizzyingly short stretch of time. It's reasonable to wonder how many among us will end up being one of the "costs" that are slashed.

This is far from a cutting-edge question. Replace robots with the labor-saving technology du jour and you'll find scores of good answers long ago provided for us to consider. The furious desperation of the mythical Ned Ludd's loom-marauding hoards in 18th century England was more articulately conveyed by Karl Marx, who posited that any laborer's time-saving machine "immediately becomes a competitor of the workman himself." Fleshy, wage-demanding laborers simply cannot win against cold, cost-minimizing machines. Capitalists bask in maximum surplus value as structural unemployment mounts. But this view should not be dismissed as Marxist sophistry. The classical economist and father of comparative advantage David Ricardo believed that labor's opposition to their technological replacement "is not founded on prejudice and error, but is conformable to the correct principles of political economy." It is understandable that a dedicated few took up arms against these disruptive industrial interlocutors—or, in Marx's case, wrote iconic broadsides anticipating and urging the mass realignment of labor-saving machines to the laborers themselves. Similar reactions guide much populist and academic antipathy to robotic advancement today.

But these labor market disruptions have in history only been the first phase in a technological paradigm-shift. Economist Joseph Schumpeter explained how messy short-term adjustment pains eventually lead to greater economic growth and alternative opportunities for displaced laborers in the long-term. It was inevitable that the buggy whip industry should fall to the mighty automobile. Humble horsewhip peddlers had good reason to grumble amid the disruption, but their jobs were at least destroyed creatively. Plenty more job opportunities in the related car, interstate, hotel, and amusement industries emerged in the wake. Schumpeter did not deny the accuracy of the Luddites' complaints, but reassured us that the cyclical innovation of the capitalist process would create more creative new industries to earn a living (at least until those, too, are destroyed). Robots may simply be the next in a long line of iterated disruptions that ultimately create more opportunities for humans.

Or perhaps this time is different. Economists Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee read the tea leaves of exponentially increasing processing power and foresee a bumpier road. They believe that humans have not been in the driver's seat this whole time at all. We've been in a race, and the machines are fast pulling ahead. The net positive creative destruction of the past two centuries may have merely been a consequence of uneven costs rather than an immutable law of economics. Labor-saving interventions in one industry can only open up new opportunities in other industries where labor has yet to be saved. Robots may soon eat all of these inefficiencies. As the cost of automation continues to drop, algorithmic intelligence and machine learning continue to improve, and humans continue to stubbornly remain human, the gains from automation of routine tasks, pattern recognition, and transport will leave little room for pesky hominid fumbling. Only the high-skilled, computationally-literate Übermenschen among us will be capable of racing against these powerful machines—for a little while, at least. We are quickly making most traditional human labor economically obsolete.

We would not be the first species to succumb to this vision. In A Farewell to Alms, economist Gregory Clark considers the plight of the horse. At first, the standard Schumpeterian story held for our equine friends. The "horse-saving" technology of rail transportation in the Industrial Revolution creatively destroyed long-distance hauling jobs, but it lowered costs such that more horses could be gainfully employed in related industries than before the technological change. Not so after the invention of the automobile. Horse employment dropped dramatically as the internal combustion engine slashed costs and displaced ponies. Glooms Clark, "there was always a wage at which all these horses could have remained deployed. But that wage was so low that it did not pay their feed."

The good news is that we are not horses. Even in the very worst case scenario, where a tiny capitalist elite owns leagues of robot slaves and holds a disproportionate share of material wealth, displaced workers will not fear the glue factory. Cheap products and social pressures would abound, simultaneously affording comfortable material standards for the masses and hopes of collective reform. Existing social frictions will likely at least slow down, if not marginally dampen, the full robotic race to maximum efficiency. Humans tend to complicate our tidy models.

This is partly because we can consciously act to shape our own destinies. Until we design a superior model, humans remain the most adaptable sentient lifeform known in existence. Of course, there are more and less productive adaptations we could choose to pursue. Unfortunately for the more cantankerous among us, the self-checkout machine that "steals" a clerk's retail job cares little for even the most passionately-shaken fist. We will need to be smarter than that. It is time for each individual to honestly assess his or her unique aptitudes and sentiments to find a creative comparative advantage appropriate for the impending robotic age—or learn to live with subsistent mediocrity. Economist Tyler Cowen provides a helpful and accessible roadmap for the proactively-inclined in Average Is Over. Just as humans presently make sub-par robots, robots presently make sub-par humans. Those who learn to leverage their human qualities that escape robots—of conscientiousness, quirkiness, service, and warmth—will thrive. Even better, we should take every opportunity to race with the machines rather than against them. Combining the best aspects of human intuition and charm with the efficiency and logic of algorithmic intelligence will make for a hard-to-beat partnership in the new new economy.

In 1930, John Maynard Keynes anticipated that mankind would solve our economic problem through the saving grace of machine technology. But this is not an especially difficult pattern for an economist to notice. Keynes' concerns were spiritual: "If the economic problem is solved, mankind will be deprived of its traditional purpose." When the burden of toil is removed from our backs, will we self-actualize in our freedom and bounty? Or might a darker nihilism of identity cripple our spirits? Economics provides us guidance in questions about structural changes in production, consumption, exchange, and distribution. It gives us no input on how to redeem our core humanity. For that, we'll need to look within ourselves.

Show Comments (40)