Pregnant Women Warned: Consent to Surgical Birth or Else

As hospitals and courts collude, pregnant women are being excluded from fundamental decisions about how they give birth.

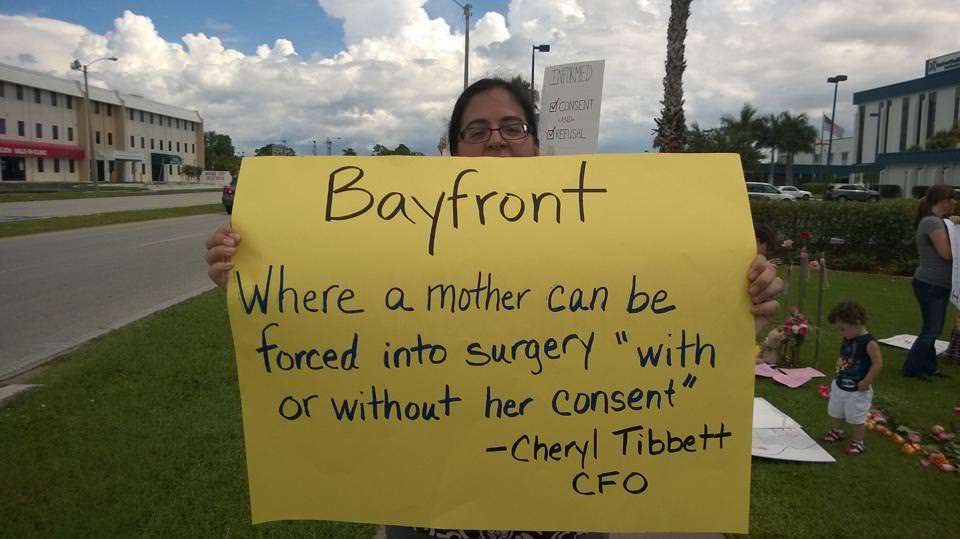

Jennifer Goodall was about to have her fourth child when the ordeal began. Having given birth to three previous children through cesarean section—a surgical procedure that allows a baby to be delivered through a woman's abdomen—the Cape Coral, Florida, mother wanted to try a natural delivery now. But in early July, Bayfront Health Port Charlotte—the hospital where Goodall had been planning on giving birth in about two weeks—told her it wasn't permitted. A letter from Bayfront's chief financial officer said if she attempted a "trial of labor," the facility would report her to the state's Department of Children and Family Services, seek a court order to perform the surgery, and do the procedure "with or without (her) consent" if she stepped foot in the hospital.

With help from the National Advocates for Pregnant Women (NAPW), Goodall sought a restraining order to prevent the hospital from taking action. There are risks and benefits involved in "c-section" delivery, both for first-time mothers and those who've had one previously. Goodall weighed those risks before coming to a decision, and was flexible should problems arise.

"I would definitely consent to surgery if there were any indication during labor that it is necessary," she said in a statement. "I am trying to make the decision that will be safest for both me and my baby, and give me the greatest chance at being able to heal quickly after my child is born so I can care for my newborn and my three other children."

In the United States, the percentage of babies born by c-section increased from 4.5 percent in 1965 to 26 percent in 2002. By 2012, it stood at 32.8 percent, according to data from the National Partnership for Women & Families. For women who have had a previous c-section, having a non-surgical delivery the next time around—a process known as vaginal birth after a cesarean section, or VBAC—can be quite controversial.

In the 1980s and 1990s, federal guidelines promoted VBAC as safe and the American College for Obstetrics and Gynecologists (ACOG) actively encouraged it. In 1999, however, ACOG updated its guidelines, after research began suggesting it might be more dangerous. After that, the VBAC rate shrunk from 27.4 percent of births in 1997 to 12 percent in 2002 and 8.4 percent in 2009. But "neonatal and maternal mortality rates did not improve despite increasing rates of repeat cesarean delivery," according to a study published in Annals of Family Medicine that looked at California data from 1996-2002. By 2010, ACOG was back to saying that VBAC was largely safe.

An analysis of 203 previous papers on VBAC found mixed outcomes. Overall rates of harm were low for both VBAC and repeat elective c-sections. The newborn mortality rate was 1.3 per 1,000 births with VBAC, compared to 0.5 for repeat c-section. Maternal mortality was 13.4 percent per 100,000 births for repeat c-section, compared to 3.8 percent for vaginal delivery. The authors concluded that "VBAC is a reasonable and safe choice for the majority of women with prior cesarean." They also noted mounting evidence that the more c-sections a woman has, the riskier the surgery becomes.

None of this means that Goodall's choice was necessarily better. But it was reasonable. This wasn't some particularly risky, out-there thing that she wanted to do. In a 2010 statement, even the National Institutes of Health (NIH) stated that "when trial of labor and elective repeat cesarean delivery are medically equivalent options, a shared decision-making process should be adopted and, whenever possible, the woman's preference should be honored."

But federal District Judge John E. Steele disagreed. In denying Goodall's request, Steele wrote that she has no "right to compel a physician or medical facility to perform a medical procedure in the manner she wishes against their best medical judgment."

That might sound semi-sensible, until you remember that the procedure Goodall wants to compel is actually the absence of forced surgical procedure. Mary Faith Marshall, director of the Center for Biomedical Ethics & Humanities at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, said that "given the clear statements from ACOG's Committee on Ethics and other professional groups that coerced or court-ordered medical procedures are not ethically justified, it is stunning that a hospital would threaten such an action."

Why would a hospital threaten such action? Fear of malpractice lawsuits seems to be the biggest reason. "Concerns over liability risk have a major impact on the willingness of physicians and health care institutions to offer trial of labor," the NIH noted. A 2009 ACOG survey found one-third of obstetricians stopped offering VBAC because they feared liability claims or litigation. (In addition, 29 percent said they had begun doing c-sections more often to avoid liability.)

The Florida Supreme Court has held that physicians aren't liable when they respect the decision of a competent and informed patient to delay or refuse a procedure. Bayfront Health could have simply made Goodall sign liability waiver paperwork, points out Farah Diaz-Tello, a staff attorney with NAPW. Instead, "what probably happened is … the hospital calculated their risk and thought that the better course of action would be to scare her away from coming in so that she would quit the practice."

In a written statement Monday, Bayfront spokeswoman Marti Van Veen said the hospital isn't opposed to vaginal births after c-section unilaterally. "Each patient has unique circumstances, and we rely on the clinical judgment of the physicians who work with their patients to make sure the birth plan is safe and supports the best possible outcomes for both mother and baby," Van Veen said.

But it doesn't seem like Bayfront Health was willing to "work with" Goodall. In the July 10 letter threatening action, CFO Cheryl Tibbett told Goodall: "We sincerely hope that you will trust your physicians and our staff to do the right thing for your unborn child, and family." Apparently doctors always know best and a patient's own preferences and decisions are a mere inconvenience to work around.

"Instead of respecting my wishes like they would for any other patient, my health care providers have made me fear for my safety and custody of my children," said Goodall. "I know I'm not the only one to go through this; I'm speaking out because pregnant women deserve better."

Rather than simply find another care provider, Goodall decided to fight back. But finding another provider isn't always so simple, either. In Goodall's case, let's remember that Bayfront rejected her birth plans just a few weeks before she was due.

Under any circumstances, finding a trustworthy new obstetrician and facility in such short time might be difficult, especially in less-populated areas. But this is compounded by circumstances like Goodall's. In the three counties surrounding her home, very few facilities will allow VBAC. Across the U.S., an estimated 40 percent of hospitals have VBAC bans, according to the International Cesarean Awareness Network.

The New York Times recently told of a Wyoming woman forced to travel 180 miles for a hospital that wouldn't force surgery on her for the birth of her second child. In one 2009 case that drew attention, a pregnant woman had to give birth at a hospital six hours from her own in order to avoid surgery. In both cases, the women and their babies turned out fine.

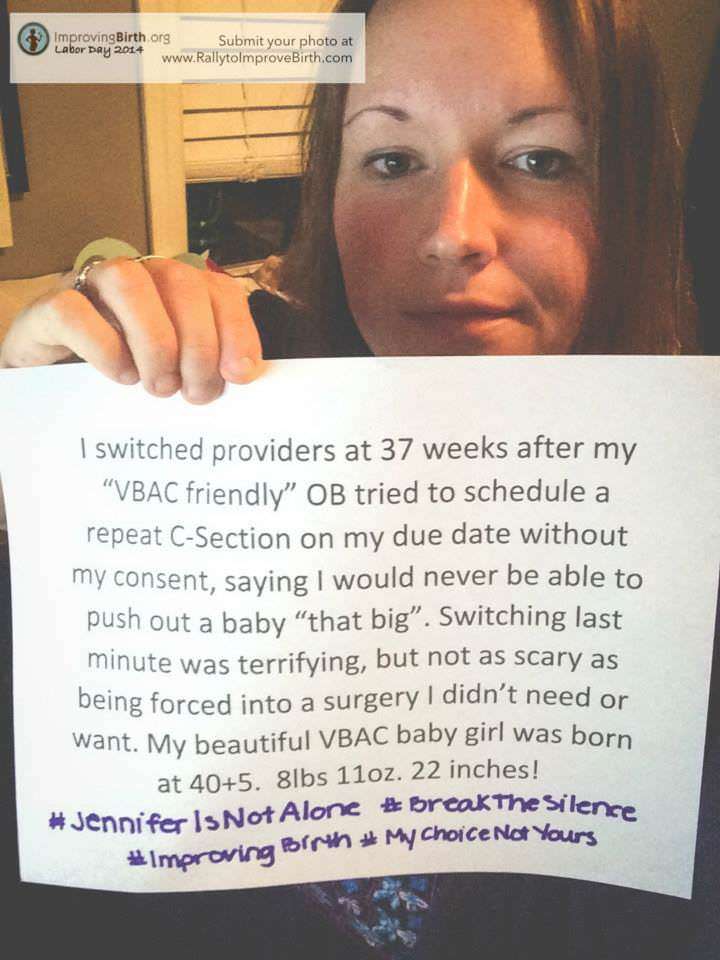

Cristen Pascucci, vice president of ImprovingBirth.org and founder of Birth Monopoly— a group devoted to improving maternity care by inbuing it with more "consumer power"—said she's spoken to hundreds of women around the country who have been forced into c-sections. With encouragement from her group and others, these women have been sharing their stories on social media and petitioning individual hospitals to end the practice.

"People do all sorts of things that create health risks—smoke, downhill ski, delay heart surgery, don't keep to diets," says Diaz-Tello. "In no other circumstance do you see doctors telling competent patients that they lose the right to decide what happens to them if they step foot in a hospital as a result."

Goodall ultimately gave birth, via c-section, at the Cape Coral Hospital. She attempted a natural delivery to start but when labor wasn't progressing, she consented to surgery. "I welcomed my son into the world … consenting to surgery when it became apparent that it was necessary," Goodall wrote on Facebook. "This was all I wanted to begin with."

Show Comments (115)