How 'Crazy Negroes' With Guns Helped Kill Jim Crow

Civil rights and armed self-defense in the South

This Nonviolent Stuff'll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible, by Charles E. Cobb Jr., Basic Books, 304 pages, $27.99

I have a dream that one day children in seventh grade will have an American history textbook that is not like my son's. Its heroes will not just be people from the past who upheld the middle-class values of modesty, chastity, sobriety, thrift, and industry. The rebels it celebrates will include not only abolitionists, suffragists, labor unionists, and civil rights leaders who confined their protests to peaceful and respectable writing, speaking, striking, and marching. In my dream, schoolchildren will read about people like C.O. Chinn.

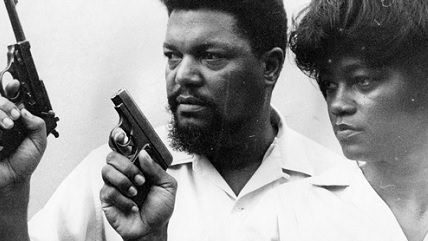

Chinn was a black man in Canton, Mississippi, who in the 1960s owned a farm, a rhythm and blues nightclub, a bootlegging operation, and a large collection of pistols, rifles, and shotguns with which he threatened local Klansmen and police when they attempted to encroach on his businesses or intimidate civil rights activists working to desegregate Canton and register black residents to vote. After one confrontation, in which a pistol-packing Chinn forced the notoriously racist and brutal local sheriff to stand down inside the county courthouse during a hearing for a civil rights worker, the lawman admitted, "There are only two bad sons of bitches in this county: me and that nigger C.O. Chinn."

Although the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) were formally committed to nonviolence, when their volunteers showed up in Canton they happily received protection from Chinn and the militia of armed black men he managed. "Every white man in that town knew you didn't fuck with C.O. Chinn," remembered a CORE activist. "He'd kick your natural ass." Consequently, Chinn's Club Desire offered a safe haven for black performers such as B.B. King, James Brown, Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, and the Platters; illegal liquor flowed freely in the county; and, unlike their comrades in much of Mississippi, CORE and SNCC activists in Canton were able to register thousands of black voters with virtual impunity from segregationist violence.

According to Charles E. Cobb's revelatory new history of armed self-defense and the civil rights movement, This Nonviolent Stuff'll Get You Killed, Canton and the rest of the South could not have been desegregated without people like C.O. Chinn, who were willing to take the lives of white people and were thus known as "crazy Negroes" or, less delicately, "bad niggers."

Cobb does not discount the importance of nonviolent protest, but he demonstrates with considerable evidence that desegregation and voting rights "could not have been achieved without the complementary and still underappreciated practice of armed self-defense." Noting that textbooks like my son's ignore the many people who physically defended the movement or themselves, Cobb shows that the "willingness to use deadly force ensured the survival not only of countless brave men and women but also of the freedom struggle itself."

The philosophy of nonviolence as propounded by Martin Luther King Jr., and the civil rights leadership that emerged in the 1950s was a new and exotic concept to black Southerners. Since before Emancipation, when slaves mounted several organized armed rebellions and countless spontaneous and individual acts of violent resistance to overseers, masters, and patrollers, black men and women consistently demonstrated a willingness to advance their interests at the point of a gun. In the year following the Civil War, black men shot white rioters who attacked blacks in New Orleans and Memphis. Even the original civil rights leadership publicly believed that, as Frederick Douglass put it in 1867, "a man's rights rest in three boxes: the ballot box, the jury box, and the cartridge box."

During Reconstruction, all-black units of the Union Leagues organized themselves as militias and warred against such white terrorist organizations as the Men of Justice, the Knights of the White Camellia, the Knights of the Rising Sun, and the Ku Klux Klan, whose primary mission was to disarm ex-slaves and thus was one of the first gun-control organizations in the United States.

With the rise of Jim Crow segregation at the end of the 19th century, civil rights leaders continued to advocate meeting fire with fire. "A Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home," the famed anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells-Barnett wrote in 1892, when on average more than one black person was lynched every three days in the South, "and it should be used for that protection which the law refuses to give."

In 1899, after a black man named Henry Denegale was accused of raping a white woman in Darien, Georgia, armed black men surrounded the jail where he was held to prevent lynch mobs from taking him. Instead of being hanged from a tree or burned at the stake, Denegale was tried and acquitted. Though blacks tended to consider Georgia the most lethal of all the Southern states, the coastal area, where Darien was located, "had the fewest lynchings of any place in the state."

One of the first victories of the modern civil rights movement came at the point of many guns. In the spring of 1947, after a black man named Bennie Montgomery in Monroe, North Carolina, was executed for murdering his white employer during a fight over wages, the local Ku Klux Klan threatened to take Montgomery's body from the funeral parlor and drag it through the streets of the town as a message to blacks who might consider assaulting whites. But when the Klansmen arrived at the funeral parlor, three dozen rifles belonging to members of the Monroe branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) were trained on their motorcade. The Klansmen fled.

This successful showdown convinced the president of the Monroe NAACP, Robert F. Williams—who later authored a book-length argument for armed self-defense titled Negroes With Guns—that "resistance could be effective if we resisted in groups, and if we resisted with guns." In addition to his duties with the NAACP, Williams established an all-black chapter of the National Rifle Association (NRA) and used his NRA connections to procure "better rifles" and automatic weapons for his constituents. Ten years after the funeral-parlor incident, those guns were used to repel a Klan assault against an NAACP leader's house. Immediately following the shootout, the Monroe City Council banned Klan motorcades and, according to Williams, the KKK "stopped raiding our community."

Theodore Roosevelt Mason "T.R.M." Howard was another black Southerner who found guns a highly effective means to gain rights. Cobb uses Howard's story in 1950s Mississippi to illustrate "the practical use of armed self-defense" for an oppressed minority. Howard, who was the chief surgeon at a hospital for blacks in the Mississippi Delta, founded the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL), an umbrella organization of civil rights groups in the state. The RCNL led a campaign against segregated gas stations, organized rallies featuring national civil rights leaders, and encouraged black businesses, churches, and voluntary associations to move their bank accounts to the black-owned Tri-State Bank, which loaned money to civil rights activists denied credit by white banks.

Knowing that he was always at risk of being attacked by white supremacists, Howard took full advantage of Mississippi's loose gun laws. He wore a pistol on his hip, displayed a rifle in the back window of his Cadillac, and lived in a compound secured by round-the-clock armed guards. Black reporters covering the civil rights movement in Mississippi often stayed in Howard's home, which contained stacks of weapons, at least one submachine gun, and, according to one visiting journalist, "a long gun, a shotgun or a rifle in every corner of every room."

According to many accounts, southwest Mississippi was the most dangerous and Klan-ridden region of the South—"the stuff of black nightmares," according to Cobb—but it was also home to several of the strongest branches of the NAACP. Activists from the area were the first in Mississippi to file a school desegregation suit, a youth chapter campaigned against police brutality, and local NAACP members traveled to D.C. to testify for the 1957 Civil Rights Act. The presidents of two NAACP branches-C.C. Bryant of Pike County and E.W. Steptoe of Amite County-offered their fortified houses as resting stops for SNCC and CORE organizers. One SNCC volunteer recalled that if you stayed with Steptoe, "as you went to bed he would open up the night table and there would be a large .45 automatic sitting next to you….[There were] guns all over the house, under pillows, under chairs." It was for that reason that SNCC operated one of its "Freedom Schools" on Steptoe's farm.

Anti-racist proponents of gun control should note an irony in this story: One aspect of Southern culture allowed for the dismantling of another. "Although many whites were uncomfortable with the idea of blacks owning guns-especially in the 1960s," Cobb writes, "the South's powerful gun culture and weak gun control laws enabled black people to acquire and keep weapons and ammunition with relative ease." One example of this came in 1954, when the Mississippi state legislator Edwin White responded to an increase in black gun ownership with a bill requiring gun registration as protection "from those likely to cause us trouble," but the bill died in committee.

Guns weren't the only physical weapons used to advance civil rights. Five days after the famous 1960 sit-in at a Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, another sit-in was attempted but the protesters were blocked from entering the store by crowds of young whites carrying Confederate flags and threatening violence. So football players from the historically black North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College formed a flying wedge and rammed through the mob. In Jacksonville, Florida, a gang of black youth known as the Boomerangs used their fists to beat back a group of whites who were attacking sit-in protestors with ax handles.

Two of the best-known civil rights organizations practicing armed self-defense were the Deacons for Defense and Justice, which was formally incorporated in Louisiana in 1965 with the explicit purpose of providing armed protection for civil rights activists, and the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) of Alabama, a SNCC affiliate that renounced the national organization's nonviolent philosophy and helped inspire the formation of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in northern cities.

The Deacons appeared at protests toting rifles and gained special notoriety when they aimed their guns at firemen who were preparing to unleash hoses on a group of black high school students in Jonesboro, Louisiana, as they picketed for black control of black schools. The LCFO—headed by Stokely Carmichael, who coined the slogan "Black Power"—was staffed by well-armed organizers who increased the number of black voters in Lowndes County from one, when the group was established in 1965, to almost 2,000 a year later.

Though national civil rights leaders publicly renounced the use of violence, many of them privately relied on it. Even the great American apostle of nonviolence himself tacitly acknowledged the value of guns. During the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955 and 1956, King applied for a permit to carry a concealed weapon. He was denied the license but filled his home with firearms and allowed armed neighbors to stand guard over his family and property. More than one visitor to King's house in Montgomery described it as "an arsenal."

King wasn't the only civil rights leader who relied on "crazy Negroes." Indeed, according to Cobb, even though most of the major civil rights organizations of the period were formally committed to nonviolence, "there were few black leaders who did not seek and receive armed protection from within the black community." Many also maintained their own means of protection. Fannie Lou Hamer, whose fearlessness as an organizer in the most violent regions of Mississippi is legendary, held no qualms about owning or using firearms. "I keep a shotgun in every corner of my bedroom," she said, "and the first cracker even looks like he wants to throw some dynamite on my porch won't write his mama again."

Cobb concludes from these and many other examples of black armed self-defense that the current tendency among liberals to think of gun rights as a cause championed by racists is wrong-headed. Though "largely associated with the conservative white Right…there was a time when people on both sides of America's racial divide embraced their right to self-protection, and when rights were won because of it."

But This Nonviolent Stuff'll Get You Killed isn't just about rights. It's also about freedom—freedom as a means and an end. This is the kind of freedom our children's textbooks won't mention, but I can guarantee at least one seventh-grader will learn.

Show Comments (85)