Boston Marathon-Style Intrusive Security Has 'Institutionalized Fear'

If we treat everyday life as a permanent state of emergency, we render ourselves helpless and at risk.

One year after a bloody bombing that made international headlines, the Boston Athletic Association, organizer of the Boston Marathon, was blunt about the new environment surrounding what was once a fun outing. "Spectators approaching viewing areas on the course, or in viewing areas on the course, may be asked to pass through security checkpoints, and law enforcement officers or contracted private security personnel may ask to inspect bags and other items being carried."

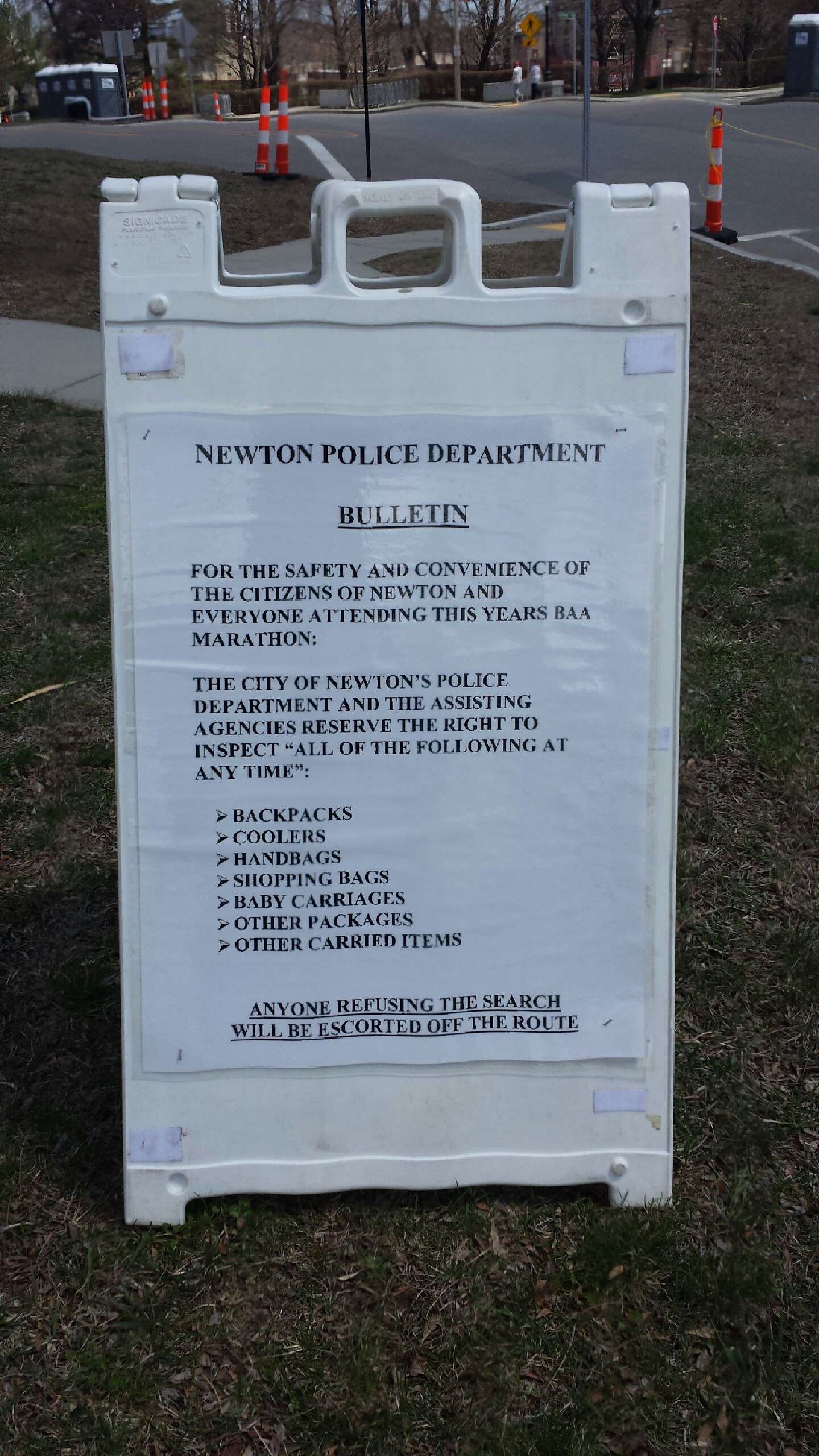

Warning signs along the marathon route pulled even fewer punches. One, posted by the Newton Police Department, not only threatened suspicionless searches, but cautioned that "anyone refusing the search will be escorted off the route."

Note that the route consists of 26 miles of public roads.

"I don't think there's a lot of safety to be gained," security expert Bruce Schneier says of the measures. "It's really for a show of force" rather than to prevent a recurrence of something like 2013's terrorist attack. Schneier believes that any new plot would have come off relatively unimpeded by the police, National Guardsmen, and checkpoints at this year's event. The very public security presence would be left to respond after the fact.

His doubts echo those of Ronald K. Noble, a former Treasury Department official and now secretary general of Interpol, the international police-coordination organization, who mused after the Westgate mall shooting in Kenya, "How do you protect soft targets? That's really the challenge. You can't have armed police forces everywhere."

A foot race route covering 26 miles, plus venues, would seem to be a very soft target, and one difficult to fully cover with police.

Not that there's much chance of those police having to respond to a terrorist attack, despite the horrors visited on attendees at the 2013 Boston Marathon. The U.S. State Department reports that 12 Americans were killed or injured around the world by terrorism in 2012. That was down from 31 in 2011. Even the roughly 3,000 people murdered by the 9/11 attacks were a small fraction of the over 42,000 killed in car accidents (PDF) that year.

Reason's own Ron Bailey calculates that an American's chance of dying in a terrorist incident is about one in 20 million—less than the chance of being struck by a lightning bolt.

But to combat that one in 20 million possibility, America's high-profile events and public places are increasingly locked down. The Superbowl in January featured similarly tight security, with checkpoints, restrictions, surveillance, and searches imposing a high cost in return for uncertain improvements in safety against a vanishingly small risk.

The security presence "has institutionalized fear," warns Schneier. "It reinforces the notion that terrorism is a big deal, when in fact…it's a really minor risk."

And institutionalized anything has a way of becoming a permanent part of the landscape. Officials and agencies are loath to surrender new powers, budgets, and toys.

"Police may implement what is billed as a temporary security regime, but then turns out to be permanent," warns Kade Crockford, director of the Technology for Liberty initiative at the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts. "All too often, when law enforcement beef up security for special events like political conventions or major sports competitions, the surveillance apparatus that's established remains firmly in place long after the crowds are gone."

Crockford worries that some or all of the security measures implemented for the marathon, such as an artificial intelligence system piggybacked on the backbone of the region's government surveillance camera network, may remain long after the runners are gone.

The dangers of terrorism are remote, the measures taken against them lingering—and there are also dangers in forcing people to submit to increasingly intrusive measures and to grow dependent on them.

"A culture of learned helplessness does create a risk," cautions Schneier.

Schneier points to the passenger revolt on Flight 93 that thwarted one of the four teams of 9/11 terrorists (though at the cost of the lives of the passengers) as an example of people taking responsibility on themselves when formal security measures couldn't do the job. Similarly, passengers and crew subdued "shoe bomber" Richard Reid in 2001 and Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab in 2009. Would people thoroughly browbeaten by security officials scrutinizing them and pawing through their possessions be so willing to stand up against terrorists?

The move toward checkpoints and bans on, in the words of race organizers, "weapons or items of any kind that may be used as weapons," at the Boston Marathon may be precisely the wrong response to a rare, but fluid danger when, as Interpol's Noble points out, armed police can't protect every possible target.

Recognizing the obvious limits of security measures after the Westgate mall shooting, Noble also commented, "You have to ask yourself, 'Is an armed citizenry more necessary now than it was in the past with an evolving threat of terrorism?' This is something that has to be discussed."

Empowering—even just allowing—regular people to respond to rare terrorist incidents, like the passengers on Flight 93 and the people who subdued Richard Reid in 2001 and Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, might not only be more effective against terrorists than a "show of force," it would also allow us to live normal lives. We could go about our business, responding only in the unlikely event that a threat actually arose.

"We can't treat everyday life as if we are living in a permanent state of emergency," notes the ACLU's Crockford.

Well…we could. But then we'd be rendered helpless and at risk by institutionalized fear.

Show Comments (32)