George Washington: Boozehound

Prodigious alcohol consumption by Washington and his fellow founding fathers has been whitewashed from American history.

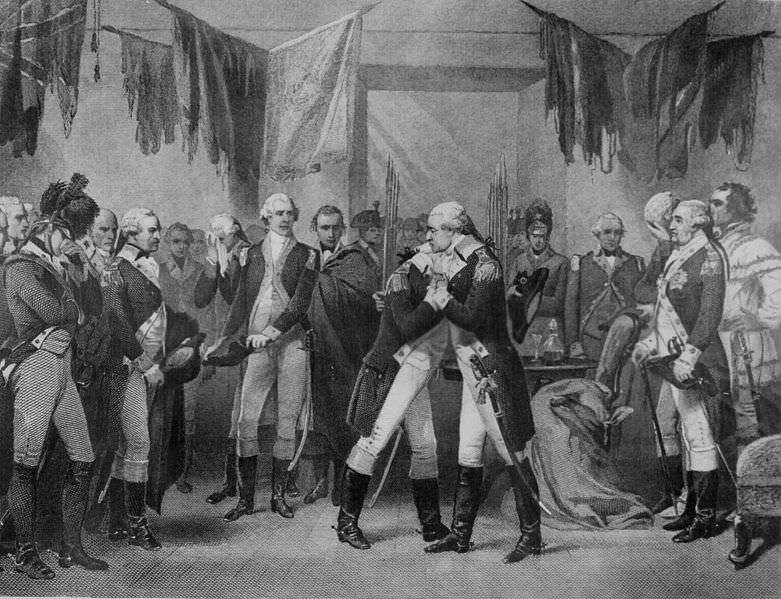

Reason TV's Meredith Bragg informed us of George Washington's whiskey production. He didn't tell us, however, about Washington's alcohol consumption, which was, at times, prodigious. That consumption by Washington and his fellow founding fathers has been whitewashed—sometimes literally—from American history by the intervening Temperance movement, whose effects still drive us. For instance, the classic picture of Washington taking his farewell from his troops at Fraunces Tavern in New York—which, of course, involved a toast—was painted with a serving flask clearly visible. This container was painted out of these same pictures later, in the nineteenth century, reminiscent of Soviet photos with purged former leaders excised.

It is impossible for Americans to accept the extent to which the Colonial period—including our most sacred political events—was suffused with alcohol. Protestant churches had wine with communion, the standard beverage at meals was beer or cider, and alcohol was served even at political gatherings. Booze was served at meetings of the Virginian and other state legislatures and, most of all, at the Constitutional Convention.

Indeed, we still have available the bar tab from a 1787 farewell party in Philadelphia for George Washington just days before the framers signed off on the Constitution. According to the bill preserved from the evening, the 55 attendees drank 54 bottles of Madeira, 60 bottles of claret, eight of whiskey, 22 of porter, eight of hard cider, 12 of beer, and seven bowls of alcoholic punch.

That's more than two bottles of fruit of the vine, plus a number of shots and a lot of punch and beer, for every delegate. That seems humanly impossible to modern Americans. But, you see, across the country during the Colonial era, the average American consumed many times as much beverage alcohol as contemporary Americans do. Getting drunk—but not losing control—was simply socially accepted.

By contrast, the Temperance movement insisted that alcohol was a beverage whose use inexorably progressed to alcoholism. I sport in my apartment the eight illustrations of George Cruikshank's "The Bottle." In the first, "Frances Latimer brings the bottle out for the first time; he induces his wife to take a drop." By the fourth plate: "Unable to obtain employment, they are driven by poverty into the street to beg, and by this means they still supply the bottle." And four more plates remain where (spoiler alert) things get "progressively" (as in alcoholic progression) worse.

Note: Cruikshank was English, and provided the illustrations for Charles Dickens' early books. But Dickens, who favored the workingman's right to drink (as well, certainly, as his own!), grew alienated from Cruikshank, the Temperance nudge.

This type of Temperance propaganda has so suffused our consciousnesses that even the most liberated among us view alcohol and drugs as leading to the kind of addictive progression represented by Cruikshank's illustrations. At the time Temperance held sway in the U.S., opiates were widely dispensed to men, women, and children in tincturated forms such as laudanum. Yet, today, we are convinced by every drug scare that comes down the pike that we cannot possibly control the effects of narcotics and other drugs, let alone alcohol.

As Ilse Thompson and I note in Recover! Stop Thinking Like an Addict:

Here's the story: a way of thinking about addiction has grown up in the United States based on our temperance history. It is furthered by our modern "brain revolution," supposedly steeped in the biology of behavior and reinforced by an economic juggernaut, that purports to find in neuroscience a full and tidy explanation for addictive behavior. Unfortunately, these cultural beliefs bear little resemblance to the reality of addiction and are not just unhelpful—but detrimental—to people who develop addictions. This is because both the 12 steps and the "new" neuroscience strive to convince you that you are an addict and will always remain an addict, which, by and large, isn't true. And if you dispute any part of this story, you are in denial, proof positive of everything they say.

And, come on, even the most radically permissive substance users among us are horrified by the amounts drunk at that Philadelphia tavern by our nations' leading political figures 227 years ago.

Show Comments (100)