Leaked ICE Memo Claims Agents Can Enter Homes Without Judicial Warrants

Under this understanding of the Fourth Amendment, an attorney at the Institute for Justice says, “there is little left of the rights of Americans to be secure in their houses.”

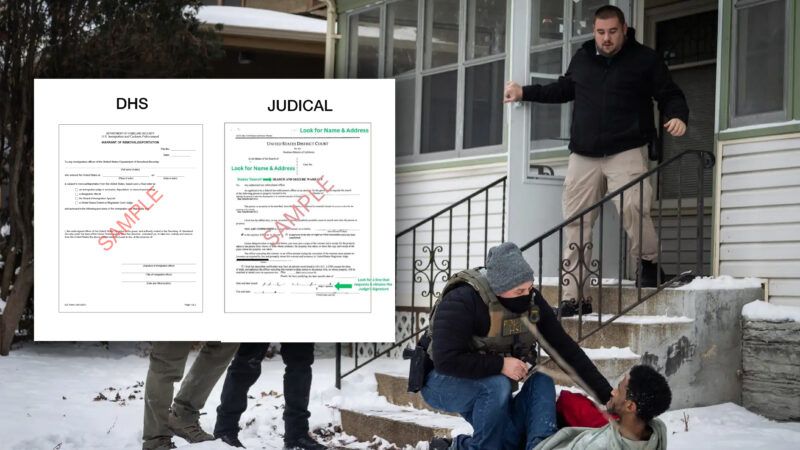

Whistleblowers have shared an internal Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) memo with Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D–Conn.). The document claims that ICE officers may enter homes without consent while conducting certain immigration arrests without a judicial warrant. This sweeping power would be an alarming violation of Americans' well-founded constitutional right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures.

Signed by acting ICE Director Todd Lyons in May of last year, the memo states that agents may rely on a certain administrative warrant issued alongside a final order of removal to use "a necessary and reasonable" amount of force to the named individual's residence if officers are denied entry.

The memo concedes that "historically," these administrative warrants alone have not been used to arrest immigrants in their homes without first obtaining consent to enter. But the Office of General Counsel at the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has apparently decided that such action is permissible when a Form I-205, a kind of administrative warrant of removal/deportation, is "supported by a final order of removal issued by an immigration judge…because that order establishes probable cause."

The whistleblowers say that physical copies of the guidance weren't circulated widely. But its contents, they report, were used to train recruits amid ICE's push to hire 10,000 agents last year. Although written 2025 training materials clearly state "a warrant of removal/deportation does NOT alone authorize a 4th amendment search of any kind," the whistleblowers say that instructors at the DHS Federal Law Enforcement Training Center "are directed to verbally train all new ICE agents to follow this policy while disregarding written course material instructing the opposite."

Legal scholars have pushed back on the agency's legal justification for this policy. Patrick Jaicomo, an attorney at the Institute for Justice, tells Reason that the memo provides "neither legal authority nor analysis." Given how secretive the government has been about this policy, Jaicomo suspects they don't have a strong case. "For good reason," he says. "The policy is unconstitutional."

"The Fourth Amendment and supporting caselaw is clear that houses cannot be searched without warrants," says Jaicomo. "Warrants must be issued by judges—not other police."

In response to the Associated Press' initial report on the leaked memo, Tricia McLaughlin, the DHS assistant secretary of public affairs, posted on X that "administrative warrants have been used for decades and recognized by the Supreme Court."

"In every case that DHS uses an Administrative warrant to enter a residence, an illegal alien has already had their full due process and a final order of removal by a federal immigration judge," McLaughlin's post continued. "The officer also has probable cause."

This justification is ignorant of the law, says Jaicomo. Americans have the constitutional right under the Fourth Amendment "to be secure in their…houses…against unreasonable searches and seizures." This right is violated if officers enter an individual's home without a proper judicial warrant, consent, or exigent circumstances not applicable to immigration arrests.

"The government is taking the position that [an] 'administrative warrant'—a warrant issued by a member of the executive branch, not the judiciary—satisfies this standard. It does not," Jaicomo says. Indeed, in Shadwick v. City Tampa (1972), the Supreme Court upheld that the "Court long has insisted that inferences of probable cause be drawn by 'a neutral and detached magistrate, instead of being judged by the officer engaged in the often competitive enterprise of ferreting out crime.'"

Since administrative warrants are signed by an immigration judge—despite the job title, that's an executive rather than judicial officer—it removes any meaningful check on the executive branch, according to Jaicomo. "An administrative warrant is not a warrant at all," he says, "it's a warrant-shaped object."

Despite these constitutional problems, challenging ICE's policy will be difficult. While a few legal avenues exist to challenge either the policy or immigration officers who enter a home without a judicial warrant—including tort claims under the Federal Tort Claims Act and hard-to-prove injunctive relief lawsuits—these "are far more limited than they should be," says Jacimo. A more meaningful fix would be for Congress to pass a law to allow claims against federal officials who violate constitutional rights.

"If McLuaghlin's understanding of the Fourth Amendment prevails," Jaicomo says, "there is little left of the rights of Americans to be secure in their houses."