Mass Surveillance Is Powering a New Era of Pretextual Traffic Stops

An extensive network of automatic license plate readers is being used to develop predictive intelligence to stop vehicles, violating Americans’ rights.

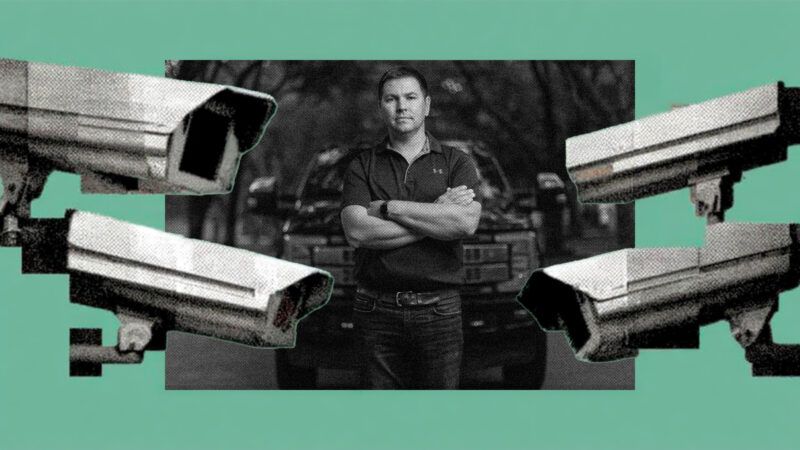

Alek Schott was driving near San Antonio when a Bexar County sheriff's deputy pulled him over for allegedly drifting lanes. Though dashcam footage later confirmed that Schott never drifted, he was interrogated for 10 minutes before the deputy called for a drug dog. After officers claimed the dog alerted to the presence of drugs, Schott was held on the side of the road for over an hour as police ransacked the truck but found nothing.

Unfortunately, it is not uncommon for law enforcement to use a minor traffic violation as a pretext to stop a driver and investigate for a bigger offense. While officers used to rely mostly on hunches to decide which vehicles to stop, they are increasingly turning to predictive intelligence that tracks and analyzes driving patterns across the United States, according to recent reporting by the Associated Press.

Well before Schott was stopped, federal agents had observed him making an overnight trip to Carrizo Springs, Texas, and staying at a hotel near the U.S.-Mexico border. Agents even knew Schott had met with a woman before driving to a business meeting together. According to court testimony and documents reviewed by the A.P., the sheriff who eventually pulled Schott over had received information about the driver from a WhatsApp group, called Northwest Highway, where state and federal cops traded information on allegedly suspicious vehicles. (In fact, Schott was on a work trip.)

The information sharing extends far beyond first-hand observations through a group chat. According to the A.P., the sheriff's deputy in Schott's case testified that federal agents "watch travel patterns on the highway" and "have a lot of toys over there on the federal side."

The U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), for example, has developed a dragnet of frequently disguised "checkpoints…surveillance towers, Predator drones, thermal cameras and license plate readers" capable of tracking vehicles' and drivers' locations, the A.P. reports. This network includes not just automatic license plate readers owned and operated by the CBP, but also those owned and operated by the Drug Enforcement Administration and by local law enforcement funded by a federal program, Operation Stonegarden. The CBP also accesses data from privately owned license plate reader systems, including Flock Safety, Rekor, and Vigilant Solutions. (The Department of Homeland Security has also tapped those systems for the Trump administration's mass deportation campaign.) This adds up to an enormous surveillance apparatus. One Border Patrol agent bragged about tracking a vehicle as it drove from "Dallas, Little Rock, Arkansas, and Atlanta" to San Antonio.

Rather than CBP agents making stops themselves, local law enforcement is notified of drivers traveling "abnormal" routes and then makes a pretextual stop. Called "whisper," "intel," or "wall stops," the true reason behind the stop is often kept a secret, even from courts. Sometimes drivers are then arrested. Other times, officers seize the driver's assets under the mere suspicion of being connected to a crime, a practice known as civil forfeiture. Officers frequently leave empty-handed, as in Schott's case. "Nine times out of 10, this is what happens," said the deputy who pulled Schott's over, according to records obtained by the A.P.

Schott was pulled over in 2022. We know about the surveillance operation used to target him because the Institute for Justice (I.J.), a public interest law firm, filed a lawsuit on Schott's behalf alleging that Bexar County, Texas, and the officers who stopped him violated his Fourth Amendment right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures. What started as a "clear-cut example of an unconstitutional traffic stop," I.J. attorney Christie Hebert told the A.P, ended up uncovering "something much larger—a system of mass surveillance that threatens people's freedom of movement."

"I assume for every one person like me, who's actually standing up, there's a thousand people who just don't have the means or the time or, you know, they just leave frustrated and angry. They don't have the ability to move forward and hold anyone accountable," Schott told the A.P. "I think there's thousands of people getting treated this way."