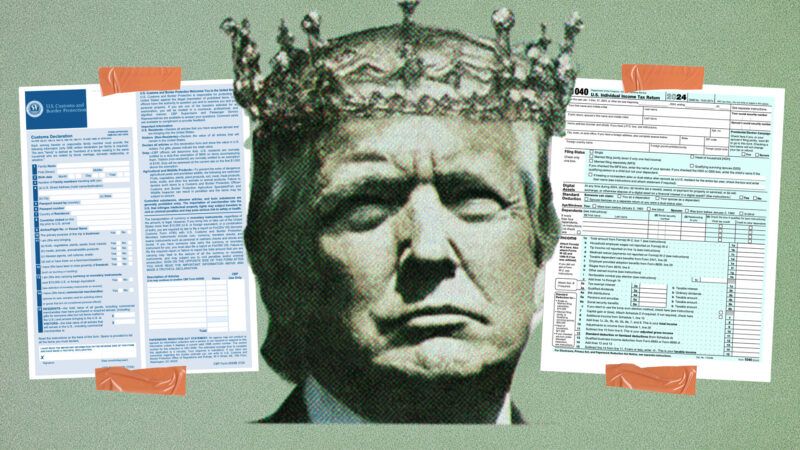

Coming Soon to the Supreme Court: Are Tariffs Taxes?

The correct answer is: Yes, even when they are also regulations. Whether the Court agrees could determine the future of presidential power.

President Donald Trump has used the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to levy duties on $2.2 trillion worth of imports. Next month, the Supreme Court will hear arguments about whether those tariffs are constitutional.

The Constitution unambiguously and explicitly grants the power to raise revenue to Congress; for the president to possess these taxing powers, Congress must explicitly delegate them in statute. Yet Chad Squitieri, a law professor at Catholic University, recently argued in The Washington Post that "not all tariffs are taxes—at least not in a constitutional sense." Instead, he wrote, they were recognized as a trade regulation.

But regulations and taxes are not mutually exclusive concepts. The Founders and the Supreme Court have recognized that tariffs are both.

In 1824, James Madison wrote that a tariff can simultaneously exist both for "the purpose of revenue" and to "foster domestic manufactures." Madison recognized that regulatory tariffs have incidental revenue effects, argues Phil Magness, an economic historian at the Independent Institute and co-author of the Anti-Tariff Declaration. The Founders understood tariffs as simultaneously exercising the Constitution's revenue and commerce clauses, which is why "every tariff bill that Congress passed from 1789 [to today] starts with 'An act to raise revenue for the United States' or something of that nature," explains Magness.

The Supreme Court has also recognized tariffs' dual nature. In its 1928 ruling in J.W. Hampton v. U.S., the Court refers to duties and taxes interchangeably. It also recognized that the existence of other motives in "fixing the rates of duty" does not transform a revenue act into something else. So if the IEEPA invokes Congress' tariff power, as Squitieri says it does, it necessarily invokes its taxing power.

Squitieri contends that the IEEPA delegates the tariff power constitutionally because the major questions doctrine, which holds that Congress may not implicitly delegate congressional powers on issues of great economic or political significance, does not apply "in cases concerning foreign affairs and national security." But this doctrine absolutely applies to revenue acts, which is exactly what the IEEPA becomes when interpreted as granting the tariff-tax power.

Squitieri also argues that the IEEPA's delegation of tariff power to the president is constitutional because it limits "when tariffs can be imposed and how long the tariffs can last," as required by the "intelligible principle" established in Hampton.

Scott Lincicome, vice president of general economics at the Cato Institute, counters that the IEEPA includes no limiting principle. "We know from the tariffs in place that there are no actual limits to the connection between the tariffs and the emergency….This is just unlimited presidential economic power: Declare national emergency for any reason; refresh it once a year; and regulate anything that touches foreign commerce."

In April, Trump deemed the "large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits" to be an "unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and economy of the United States" to impose his "reciprocal" IEEPA tariffs. But Lincicome says the goods trade deficit is neither unusual nor extraordinary: "They've been around for 30-plus years and the U.S. economy has expanded and contracted completely independent of those." Lincicome adds that there's "a strong correlation between a rising trade deficit and [an] expanding economy," making "the whole premise of the national emergency" false.

Even during a national emergency, Congress may not delegate unlimited tariff power to the president. In 1971, President Richard Nixon invoked the Trading With the Enemy Act to impose a 10 percent tariff on imports during the macroeconomic turbulence caused by the end of the Bretton Woods system. The Court of Customs and Patent Appeals upheld his tariff because it was narrowly limited by an intelligible principle and only lasted four months. (Trump's tariffs, meanwhile, were announced half a year ago and are supposed to be lifted only when the president "determines that the threat posed by the trade deficit is…resolved.") The court emphasized that "the declaration of a national emergency is not a talisman enabling the President to rewrite the tariff schedules."

By Squitieri's argument, so long as the president continues re-upping an imagined national emergency, he may impose whatever tariff rates he wants, on whichever countries he wants, for however long he wants. The Constitution, 250 years of jurisprudence, and common sense all say otherwise.